The ice having been broken by councils with portions of the Comanche, Wichita, and Kiowa Indians, it was arranged that a grand council should be held between the white officers and the chiefs of the tribes present. At ten o’clock the next day the chiefs began to assemble at the place appointed for the meeting, which was in a wood two hundred yards from the Dragoons’ camp. The Indians came from every direction until there were more than two thousand mounted and armed Indians around the council, against whom the pitiful little handful of sick, weary, and emaciated Dragoons would have had small chance; and that the Indians were restrained from violence against the whites who by their association were in the position of espousing the Osage, was due to the tact of Colonel Dodge, and to the good feeling made possible by bringing and delivering to their friends the prisoners taken by the Osage.

“The father of the Kiowa girl, having learned that she was to be restored, in a speech addressed to the Kiowas whose numbers every moment increased, gave vent to his joy and praise of his white friends… Great excitement prevailed among the Indians; but especially with the Kiowas, who embraced Col. Dodge and shed tears of gratitude for the restoration of their relative. An uncle of Wa-ha-sep-ah, a man of about 40 years of age, was touchingly eager in his demonstrations, frequently throwing his arms around Col. Dodge, and weeping over his shoulder, thus invoking blessings upon him, in a manner the most graceful and ardent. The women came in succession and embraced the girl, who was seated among the chiefs. The council being now in order, and the pipes having made their rounds, Col. Dodge addressed the Camanche chief, who sat at his right, and who interpreted his words to the Kiowas, whilst a Toyash Indian, who speaks the Caddo tongue, communicated with the Toyash men from Chiam, and one of our Cherokee friends, who speaks English and Caddo.”

During Colonel Dodge’s speech, another band of Kiowa, about sixty in number, rode up led by a chief, handsomely dressed.

“… He wore a Spanish red cloth mantle, prodigious feathers, and leggings that followed his heels like an ancient train. Another of the chiefs of the new band was very showily arrayed: He wore a perfectly white, dressed deer-skin hunting shirt, trimmed profusely with fringe of the same material, and beautifully bound with blue beads, over which was thrown a cloth mantle of blue and crimson, with leggings and moccasins entirely of beads. Our new friends shook hands all around, and seated themselves with a dignity and grace that would well become senators of a more civilized conclave.”

The Indian prisoners having been restored to their friends, the naked little Matthew Martin delivered to Colonel Dodge, and the delicate negotiations having achieved the ultimate purpose of the expedition – the promise of representatives of western tribes to accompany Colonel Dodge to Fort Gibson, that officer at once set his face toward the east. With his command were fifteen Kiowa, including Titche-totche-cha, who were the first mounted and equipped ready to march. The Comanche chief, cautious and suspicious, deferred until late, when four Comanche and squaws and their early acquaintance the Spaniard, joined the command. Wa-ter-ra-shah-ro, a Waco chief, speaking the language of the Wichita, and two warriors of the latter tribe, also rode into camp prepared for the adventure. Wheelock does not give the numbers, but many of the men, including the officers, were sick from eating the green corn, dried horse and buffalo meat furnished by the Indians, and there was no doctor with them. Their provisions were so far reduced that they were obliged to subsist on parched corn and dried buffalo meat obtained from the Kiowa. On their arrival at the sick camp at the Comanche village, they found lieutenants Izard and Moore both down with fever, and Mr. Catlin was still very ill, among the total of twenty-nine sick. The next day they broke up the camp, and all started on the march to Fort Gibson. From there they pursued a course farther to the north than their western route. That day the heat was overpowering, and before night there were forty-three ill, seven of whom were past sitting on their horses and had to be carried on litters suspended between those animals. They were almost famished for nourishing food and that with raging fevers, the waste of physical strength and a scourging sun had filled their cup of misery. It was nearly noon of the third day, Wheelock records, that

“the cry of buffalo was heard and never was the cheering sound of ‘land’ better welcomed by wearied mariners, than this by our hungry columns. The command was halted, and soon went together the report of Beatte’s rifle and the fall of a fat cow. Halted at 4 o’clock; killed two more Buffaloes, passed today more plaister of paris; rode today over open rolling prairies, between two forks of the Washita. Met a small party of Toyash Indians; our red friends suffered exceedingly from the heat of the sun; we covered them this morning with shirts.”

The next day they crossed the Washita River, and the next found them still in the buffalo country. Wheelock notes

“men in fine spirits; abundance of buffalo meat; course northeast; distance 10 miles; encamped on a branch of the Canadian; three buffaloes killed this morning; no news yet from express; anxiously looked for… One of the Kiowas killed three buffaloes with three arrows.”

On the first day of August they crossed to the north side of Canadian River fifteen or twenty miles south of where is now Oklahoma City. There they rested for two days, moved camp a mile on the third; on the fourth followed the course of the river south eight miles where they again camped near the site of the future Oklahoma State University. They remained until the sixth. During these five days they were engaged in killing buffaloes and curing the meat for the anticipated march to Fort Leavenworth, four hundred miles away, to which post they were under orders to report; fortunately for these pitifully emaciated dragoons these orders were later changed so they went to Fort Gibson first.

Catlin’s Views on the Prairies of Norman, Oklahoma

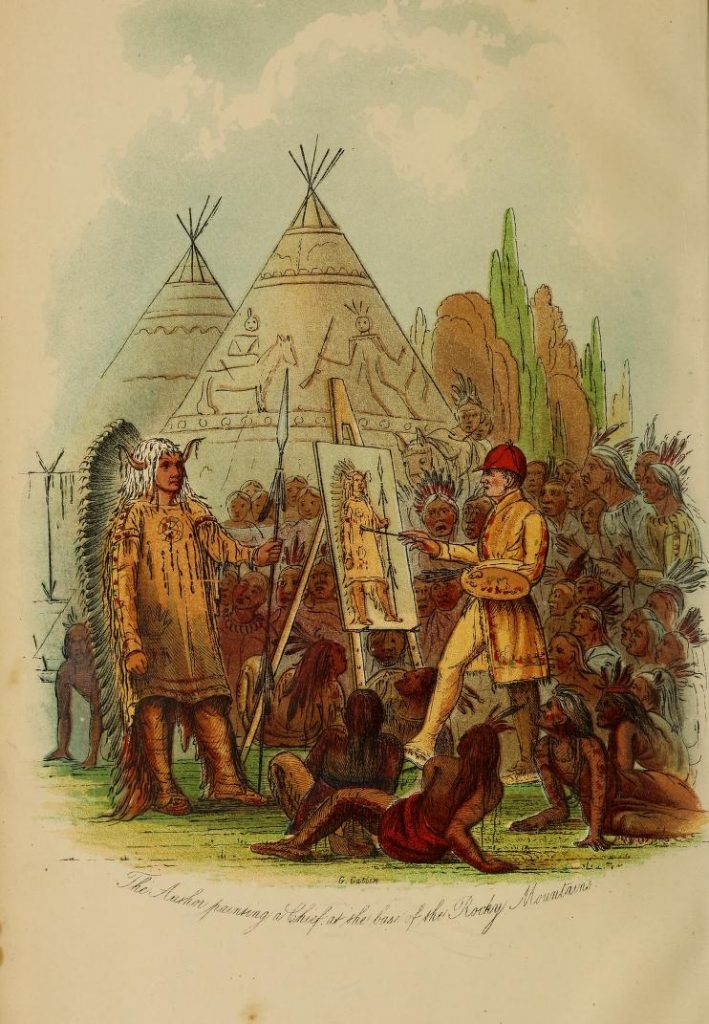

In these camps Wheelock says they saw “large herds of buffaloes; the Kiowas dashed in amongst them and killed with their bows a vast many of them. Grass very much dried… The prairie took fire today near our camp and was with difficulty extinguished.” Though very sick Catlin was able to enjoy the prairies upon which Norman, Oklahoma, is built; he said: 1

“We are snugly encamped on a beautiful plain, and in the midst of countless numbers of buffaloes; and halting a few days to recruit our horses and men, and dry meat to last us the remainder of the journey.

“The plains around this, for many miles, seem actually speckled in distance, and in every direction, with herds of grazing buffaloes.” The officers and men who were well enough to sit on their horses were engaged in killing buffaloes much in excess of any possible demand for their meat; Catlin deplored the riot of killing:”… the men have dispersed in little squads in all directions, and are dealing death to these poor creatures to a most cruel and wanton extent, merely for the pleasure of destroying, generally without stopping to cut out the meat. During yesterday and this day, several hundreds have undoubtedly been killed, and not so much as the flesh of half a dozen used. Such immense swarms of them are spread over this tract of country; and so divided and terrified have they become, riding their enemies in all directions where they run, that the poor beasts seem completely bewildered – running here and there, and as often as otherwise, come singly advancing to the horsemen, as if to join them for their company, and are easily shot down. In the turmoil and confusion, when their assailants have been pushing them forward, they have galloped through our encampment, jumping over our fires, upsetting pots and kettles, driving horses from their fastenings, and throwing the whole encampment into the greatest instant consternation and alarm.”

On the fifth an express brought word of the death of General Leavenworth west of the Washita, July 21, of bilious fever. Colonel Dodge then sent orders to Colonel Kearny at Camp Smith near the Washita, to move his command with the sick to Fort Gibson. The stop on the Canadian was intended as a rest for the sick as well as to secure meat, and while encamped there nearly all the tents belonging to the officers had been converted into hospitals for the patients; and Catlin who was one of them records that:

“”…sighs and groaning are heard in all directions… From day to day we have dragged along, exposed to the hot and burning rays of sun, without a cloud to relieve its intensity or a bush to shade us, or anything to cast a shadow except the bodies of our horses. The grass, for a great part of the way, was very much dried up, scarcely affording a bite for our horses; and sometimes for the distance of many miles, the only water we could find, was in stagnant pools, lying on the highest ground, in which the buffaloes have been lying and wallowing, like hogs in a mud-puddle. We frequently came to these dirty lavers, from which we drove the herds of buffaloes, and into which our poor and almost dying horses, irresistibly ran and plunged their noses, sucking up the dirty and poisonous draft, until, in some instances, they fell dead in their tracks -the men also (and oftentimes amongst the number, the writer of these lines) sprang from their horses, and ladled up and drank to almost fatal excess, the disgusting and tepid draft, and with it filled their canteens, which were slung to their sides, and from which they were sucking the bilious contents during the day.

“This poisonous and indigestible water, with the intense rays of the sun in the hottest part of the summer is the cause of the unexampled sickness of the horses and men. Both appear to be suffering and dying with the same disease, a slow and distressing bilious fever, which seems to terminate in a most frightful and fatal affection of the liver.”

Colonel Dodge’s March

Having received the news of General Leavenworth’s death, after a rest of five days, Colonel Dodge’s command took up their march southeast for the mouth of Little River. At once they entered the Cross Timbers where the black jack saplings were so close together they were frequently compelled to cut an opening with axes before the horses could pass. Five extremely sick men were then being carried on litters swung between the horses and the condition of these men was wretched in the extreme as their horses fought through the thickets that clawed and buffeted the improvised litters carrying the miserable burdens.

While they had acquired buffalo meat in plenty, they had no other wholesome food; and the man who had saved a little of his allowance of corn was envied by the others. The scarcity of water added to the suffering of man and beast, both sick and well. After hours of weary travel under a broiling sun, a fringe of low lying timber indicated the bed of a stream and shade, and seemed to invite them to refreshing water. Winding down the steep bank through cottonwoods and willows, to the dry crossing at the bottom, the patient horses looked longingly up and then, turning, gazed down the parched surface for the pools that instinct told them should be there. And the men gazed in vain at the cottonwoods and willows which marked only where water had been.

And so they continued to Camp Holmes, at the mouth of Little River, where they found a large number of sick to add to their list of thirty, but here at least Dodge’s men were rejoiced by pork and flour. They received word from Colonel Kearny that there were one hundred forty-one sick and seventy-nine men fit for duty on the Washita. At the Creek settlements on North Fork, the horses were made happy by the first feed of corn, and Colonel Dodge learned that the frantic mother of little Matthew Martin had offered two thousand dollars for his return, little knowing that she was so soon to be made happy by his restoration, without price. Against a hot wind that burned the face, alternately walking and leading and riding the enfeebled horses, they marched on to Fort Gibson, where they arrived on the fifteenth, a handful of sorry looking figures, half-naked and emaciated, with nothing to identify them as the splendid, vigorous troopers who left that place two months before.

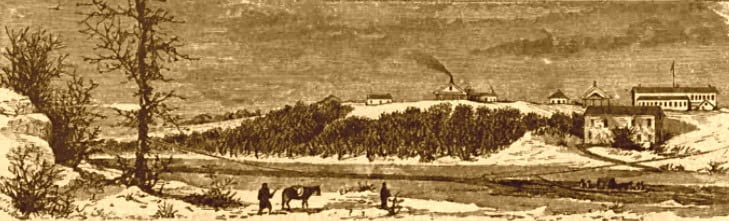

Colonel Dodge and staff and the Indians crossed to the Post, while the dragoons camped on the west side of the Arkansas. It was the twenty-fourth of the month before part of Colonel Kearny’s command arrived from the Washita with his pitiful caravan of sick men and worn-out horses; those too sick to travel with the first contingent followed in wagons and litters. The scenes at Fort Gibson after the return of the dragoons are well described by Catlin. 2

“Fort Gibson, Arkansas

The last Letter was written from my tent, and out upon the wild prairies, when I was shaken and terrified by a burning fever, with home and my dear wife and little one, two thousand miles ahead of me, whom I was despairing of ever embracing again… I am yet sick and very feeble, having been for several weeks upon my back since I was brought in from the prairies. I am slowly recovering, and for the first time since I wrote from the Canadian, able to use my pen or my brush.

“We drew off from that slaughtering ground a few days after my last Letter was written, with a great number sick, carried upon litters with horses giving out and dying by the way, which much impeded our progress over the long and tedious route that lay between us and Fort Gibson. Fifteen days, however, of constant toil and fatigue brought us here, but in a most crippled condition. Many of the sick were left by the way with attendants to take care of them, others were buried from their litters on which they breathed their last while traveling, and many others were brought in to this place, merely to die and get the privilege of a decent burial.

“Since the very day of our start into that country, the men have been continually falling sick, and on their return, of those who are alive there are not well ones enough to take care of the sick. Many are yet left out upon the prairies, and of those that have been brought in and quartered in the hospital, with the soldiers of the infantry regiment stationed here, four or five are buried daily; and as an equal number from the 9th [Seventh] Regiment are falling by the same disease, I have the mournful sound of ‘Roslin Castle,’ with muffled drums, passing six or eight times a-day under my window, to the burying ground, which is but a little distance in front of my room, where I can lay in my bed and see every poor fellow lowered down into his silent and peaceful habitation. During the day before yesterday, no less than eight solemn processions visited that insatiable ground.

“…After leaving the headwaters of the Canadian, my illness continually increased, and losing strength every day, I soon got so reduced that I was necessarily lifted on to and off from my horse; and at last, so that I could not ride at all. I was then put into a baggage wagon which was going back empty, except with several soldiers sick, and in this condition rode eight days, most of the time in a delirious state, lying on the hard planks of the wagon, and made still harder by the jarring and jolting, until the skin from my elbows and knees was literally worn through, and I almost ‘worn out’; when we at length reached this post, and I was taken to a bed, in comfortable quarters, where I have had the skillful attendance of my friend and old schoolmate, Dr. Wright under whose hands, thank God, I have been restored, and am now daily recovering my flesh and usual strength.”

The expedition was rated as successful, 3 inasmuch as it resulted in actual contact with the wild western prairie Indians, and subsequent treaties with them, though at an appalling cost. The Administration was subject to scathing criticism for the management of the expedition which left Fort Gibson six weeks too late, exposing to the perils of the climate recruits unprepared for the risk by training or experience; three troops of the dragoons having but three days to rest between their arrival from Jefferson Barracks and their departure for the Southwest.

Council of Colonel Dodge and Western Indian Tribes

Soon after the return of Colonel Dodge to Fort Gibson runners were sent to the chiefs of the Osage, Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw and other tribes, for the purpose of assembling them in council with the western Indians who accompanied the expedition to the post. On September 2, the council met at noon. Major F. W. Armstrong, who had been commissioned to wind up the affairs of the late commissioners stationed at Fort Gibson, had just arrived from Washington in time to take part in the conference. Governor Stokes, whose commission of office had expired, had remained at Fort Gibson while the expedition was in the west; at the request of Colonel Dodge and Major Armstrong to give them the benefit of his information gained as commissioner, he took an unofficial part in the council.

Creek Chief

There were present at the council, Colonel Dodge, Major Francis W. Armstrong, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Western Territory; Civil John and To-to-lis, chiefs of the Seneca; Moosh-o-la-tu-bee for the Choctaw; Chisholm and Rogers for the Cherokee; Mcintosh and Perryman for the Creeks; Clermont for the Osage; Titche-totche-cha of the Kiowa; We-ter-ra-shah-ro for the Pawnee Picts and We-ta-ra-yah for the Waco. Besides these, braves of all the other tribes represented brought the number to about one hundred fifty. Lieutenant T. B. Wheelock was the secretary and recorded the proceedings of the council. 4

With mingled feelings of curiosity and suspicion, uncertainty and caution, these half-naked and wild-looking representatives of the western tribes, warily entered the rudely constructed council house at the post, and tentatively yielded to the novel experience of a council with the white men and with tribes they had never before met. The conference lasted three days and at its conclusion Colonel Dodge presented to the western Indians medals and flags given by Governor Stokes, and explained that they were symbolic of the friendship of the Great Father at Washington. Dodge and Armstrong, having no authority to enter into a treaty of peace with the western Indians, the latter requested that a promise be made to them that in the buffalo country “when the grass next grows after the snows, which are soon to fall, shall have melted away”, another conference would be held at which formal treaties would be entered into, entailing of course more substantial presents. Armstrong and Dodge assured them that they would recommend it to the President. Then the meeting adjourned.

Thus ended what was probably the most important Indian conference ever held in the Southwest; for it paved the way for agreements and treaties essential to the occupation of a vast country by one hundred thousand members of the Five Civilized Tribes emigrating from east of the Mississippi; to the security of settlers and travelers in a new country; to development of our Southwest to the limits of the United States and beyond and contributed to the subsequent acquisition of the country to the coast, made known to us by the pioneers to Santa Fe and California traveling through the region occupied by the wild Indians who, at Fort Gibson, gave assurances of their friendship. It is true, these assurances were not always regarded, and many outrages were afterwards committed on the whites, but the Fort Gibson conference was the beginning and basis upon which ultimately these things were accomplished.

Threats from the Osage Chiefs

After the conference, Colonel Dodge reported 5 that he had presented to the chiefs of the western Indians thirteen guns and two hundred fifty dollars’ worth of merchandise and tobacco as presents; and recommended that commissioners be sent to the buffalo country the next spring to make treaties with the tribes in that country. He said that on September fifth the western Indians started home, and he had sent a small detachment of dragoons to escort them out of the settlement and a small body of Cherokee to accompany them through the Cross Timbers. 6 Major Mason’s company, he said, was stationed twenty miles up the Arkansas, convenient to building-timber for the erection of huts and stables for the winter, and forage for the horses.

On the eighth the Osage Chiefs, Black Dog and Tal-lai, with one hundred members of the tribe, came to Fort Gibson and said they had just heard of the conference and desired to know what was done. They then demanded two hundred dollars for the woman prisoner who had been turned over to General Leavenworth by Hugh Love, and threatened that if the amount were not forthcoming they would overtake the western Indians who were returning home, and recapture the girl or take another in her place. Fearful that they might carry their threat into effect and destroy all that had been accomplished at an appalling cost, Colonel Dodge paid them the money on his own responsibility. He also had the great satisfaction of reporting that on the twelfth the officer had returned after restoring to his mother in Miller County, Arkansas, the little prisoner, Matthew Wright Martin.

Citations:

- Catlin, op. cit., vol. ii, 511, 512.[↩]

- Catlin, op. cit., vol. ii, 517.[↩]

- See sixth Annual Message of President Andrew Jackson, December 1, 1834. Richardson, James D., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, vol. iii, 112, 113.[↩]

- Indian Office, Retired Classified Files, 1834 Western Superintendency, Journal of Lieutenant T. B. Wheelock. This journal consists of twenty-five pages of manuscript in Wheelock’s handwriting, and is signed by Colonel Dodge and Wheelock. It is entitled, “Proceedings of a Council held at Fort Gibson, Ark. in September 1834 between Col. Dodge, U.S. Dragoons, and Col. Armstrong Supt. Ind. Affairs, I. Territory U. States, on the part of the U. States, and the Chiefs of the following tribes of Indians – viz. The Seneca, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, Osage, Kiawa, Pawnee Pict (or Toyash) and Waycoah. The three last named being the tribes known by the name of Pawnee.”[↩]

- Dodge’s Military Order Book, 90.[↩]

- “There is already in this place [Fort Gibson] a company of eighty men fitted out, who are to start tomorrow, to overtake these Indians a few miles from this place, and to accompany them home, with a large stock of goods, with traps for catching beavers, etc., calculating to build a trading-house amongst them, where they will amass at once an immense fortune, being the first traders and trappers that have ever been in that part of the country.” – Catlin, op. cit., vol. ii, 523.[↩]