The Indians, having no written language, preserved and handed down their history to future generations through tradition, much of which could have been obtained a century and a half ago, and even a century ago, which was authentic and would have added much to the interest of the history of the continent of which we boast as our inheritance, though obtained by the extermination of a race of people whose wonderful history, had it been obtained as it once could have been, would have been very interesting and beneficial to future generations, throwing its light back over ages unknown, connecting the present with the past. The traditions of all Indians had been preserved for ages back by carrying them from one generation to another by the means of careful and constant repetition. The ancient Choctaws selected about twenty young men in the jurisdiction of each chief, who were taught the traditions of the tribe, and were required to rehearse them three or four times a year before the aged men of the nation, who were thoroughly posted, that nothing might be added to or taken from the original as given to them. Besides, it is well known to all who are acquainted with the known history of the North American Indians, that before the whites had commenced the war of extermination upon them they all aided the memories of those to whom were entrusted the preservation of their traditions by symbols, called by the whites, wampum, and which they regarded, judging from their own standpoint, as the Indians money. The Indians had no money, but they held their wampum in as sacred veneration as the true Christian holds his Bible, of which the Indians had never heard. The wampum was their true and veritable history more reliable than many histories of the present day.

The wampum, or belt rather, was made of strong, broad pieces of dressed buckskin beautifully adorned with beads of various colors, to which were attached innumerable skins of dressed buckskin, at the end of which were also attached the symbols, composed of various things, such as different kinds of shells, stones, bones, quills, carved pieces of wood, teeth of bears and panthers, points of buck horns, rattlesnake rattles, and other things too numerous to mention. But each article attached had its meaning even as the printed letters or words in a book have a meaning, yet read and understood alone by the Indians. Those young men were also yearly required to interpret these symbols as well as to rehearse the traditions entrusted to their memory; and so faithfully and correctly were they required to interpret the signification of each symbol, and rehearse each tradition that generations would pass, and yet the wampum’s and tradition keepers of every tribe could read the wampum as easily and correctly as an educated white man could read a book; and tell the story of the tradition in their extreme old age as fluently and correctly as when they had first been entrusted with it in the bright days of their manhood.

Several of those ancient wampum’s are said to still exist among the feeble remnants of the once powerful confederacy of the six tribes, who when in their palmy days, together with all their race, had no memories of yesterday to annoy them nor cares for the morrow to perplex. One, it is said, contains upwards of 7000 strings of symbols relative to their war with the Huron’s assisted by Champlain and a few of his companions, to whom they attributed their defeat by the Huron’s, and for which they never forgave the French, and ever remained the inveterate and uncompromising enemies of all Frenchmen. One of the wampum’s still possessed by the confederacy is said to date back to the year 1540, and contains much concerning the treaties and the wars with the whites. But who, among the whites could read those ancient wampum’s, even if they possessed them? And even if any one of the forlorn remnants of that confederacy who could read them, was requested so to do would he comply to that request? Never. Broil him on a bed of burning coals, yet he would refuse to gratify the idle curiosity of any one. Could the ancient wampum’s of the North American Indians speak today, what a thrilling history would they narrate. But our ancestors were too deeply interested in other pursuits to pay any attention to their civilization and Christianizing, and to the collection and preservation, which would have contributed so largely to our knowledge of the past history of this continent.

Many of late have tried to ascertain the exact date of the organization of the confederacy of the five tribes, but only to end in foolish conjecture and wild speculation. One of their traditions, it is said, places it in the year 1539, but this is declared by others to be too recent a date by nearly a century; while Cornplanter, a noted Seneca chief, who died in 1836 at the advanced age of 105, stated that his tribe, the Seneca’s, once had a wampum that contained the date of the organization of the confederacy; that he had been taught to read the wampum in early manhood; that he had often readmit in his peoples counsels, and also in the yearly counsels of his tribe, and had also heard it read by others frequently; that it was destroyed in the burning of their villages by Sullivan and his soldiers in 1799; that he and the chiefs, Blacksnake, Red jacket, and a few old men of his tribe, partly restored it a few years after. But it too has forever vanished.

Cornplanter, it is said, often repeated many portions of different wampum’s, incidents and events that were known to have taken place between 1530 and 1540 and recorded in the wampum the true symbolic history of the Indians, read by them alone. But far back through the decades beyond the above mentioned years of the past, Cornplanter stated there was a wampum in which was recorded the true history of the organization of this wonderful republic, which took place at the occasion of an eclipse of the sun. He says: A darkening of the big light of the Great Spirit, which occurred during one of the months when corn was being hoed, and before the year 1540. I do not know when this occurred, but remember the statement I read in the wampum, which said it was an entire darkening of the big light of the Great Spirit many years ago in the long past.” The scene of the formation of the confederacy was in central New York. It is stated that there was a total eclipse of the sun on the 29th of July 1478 which, however, was too late in the season to fulfill the statements recorded amid the strings of the wampum. But it is also known that there was a total eclipse of the sun, visible in central New York, on the 28th of June 1451, which must be the date of the formation of the confederation of the live tribes, afterwards named Iroquois by the French.

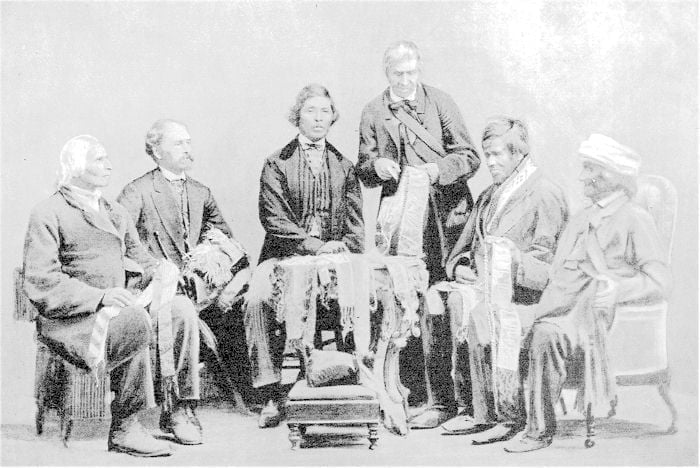

Named from left to right: Joseph Snow (Chan-ly-e-ya, Drifted Snow), Onondaga chief; George H. M. Johnson (Je-yung-heh-kwung, Double Life), Mohawk chief, official interpreter; John Buck (Skan-a-wa-ti, Beyond the Swamp), Onondaga chief, keeper of the wampum; John Smoke Johnson (Sack-a-yung-kwar-to. Disappearing Knot), Mohawk chief, speaker of the council, father of George H. M. Johnson; Isaac Hill (Te-yem-tho-hi-sa, Two Doors Closed), Onondaga chief; and John Seneca Johnson (Ka-nun g-he-ri-taws, Entangled Hair Given), Seneca chief.

Cornplanter stated that the Indians regarded the event as one long to be remembered, and gave it great prominence among the records of their historical wampum, on account of the strange and peculiar circumstances of its occurrence. He stated that a party of young Seneca warriors, then on a hunting expedition, entered the territories of the Mohawks and recklessly made prisoners of several children boys and girls with whom they at once retreated to their own country. A large party of enraged Mohawk warriors hastened in pursuit, accompanied by a strong band of Onondaga warriors. When the Mohawks and Onondagas had arrived near the territories of the Seneca’s, the Mohawks sent a small delegation of their warriors to the Seneca villages, with instructions to try to settle the matter amicably, and thus avoid the death of their captive children. But the haughty Seneca’s turned a deaf ear to the ambassadors of peace and bade them return to their own; then placed the captive children, under a strong guard on a hill near their village, that the Mohawk and Onondaga warriors might see them slain as they made their expected attack upon the village; but as the Mohawks and Onondagas were considering what best to do, and the Seneca’s standing ready to slay their captives at the first demonstration made to rescue them, the attention of one of the little captive girls was drawn to the peculiar appearance of things around, and looking up at the sun saw the great black shadow that seemed to be spreading itself over its disk. With a loud shriek she pointed to the sun, to which every eye was instantly turned, and at once the whole scene was changed from a spirit of war and revenge to that of superstitious horror and fear that cannot be described, nor scarcely imagined.

I have witnessed the effects of an eclipse upon the Choctaws before they had been taught by the missionaries its true cause. But at this auspicious moment, when no thought occupied the mind of either captives or warriors but that of astonishment and dread, an aged chief, who well knew the desolating effects of war, solemnly arose and, with eyes resting upon the fading sun and linger pointing upward, called out in a loud tone of voice, “See! The Great Spirit is spreading his hand over the face of his great light as a manifestation of his displeasure at our proceedings this day, and thus commands us to make peace at once lest he hide his great light from us forever; and never again to make war upon the Mohawks and Onondagas but to ever regard them as brothers; and to which if you will comply he will remove his hand from over his great light, and it shall continue, as it ever has before, to give us light.” At once all gladly and cheerfully agreed to the proposition; and soon the eclipse began to pass off, to the great joy of the tribe; and as soon as the sun shone out in its usual brightness and splendor, all were wholly convinced of the anger of the Great Spirit in their prospective war, and equally so, in the assurance given of his pleasure in their promise to live in peace with the Mohawks and Onondagas. At once a deputation, with the captives, was sent to the waiting but still confused and bewildered Mohawks and Onondagas, who were told what the Great Spirit had said, and what the Seneca’s had resolved and desired to do. To all of which they readily acquiesced and all returned to the Seneca village.

A council was called, a treaty was made and ratified by the three tribes, and they became as one nation. The news of the established confederacy, with the strange particulars of its conception and birth, soon reached the neighboring tribes the Oneidas and Cayugas who, in compliance to the commands of the Great Spirit, joined the confederacy without delay. And thus, if tradition be true, which no doubt it is, was formed a confederacy pledged by all the solemn and mysterious ceremonies of that peculiar people, whose descendants still linger with us as feeble shadows of their once great and happy people sparks still lingering in the ashes of an exterminated race of four centuries ago, never again to war against each other, nor refuse to assist each other in war against the common enemy, or in any misfortune or distress. From that day to this the stipulations of that solemn treaty have never been violated, according to their latest traditions, and they have ever lived as a mighty brotherhood, though four hundred and forty-eight years have passed since the formation of that mighty league of friendship and love, the most wonderful ever known to man, and with a history never to be duplicated upon earth.

As the Pyramids of ancient Egypt those miracles of stone that have defied the ravages of ages must be ascribed to the era of some great, dominant people, whose history is hidden in the silent mysteries of the past, and from whom the nations of the east have descended; so too may these ancient mounds and fortifications (and also those ruins of ancient cities and large reservoirs of water, if true) be as justly ascribed to a prehistoric race that is lost in the mists of the past, but from whom the North American Indians have also descended.

And though the advent of man upon earth is lost in the gloom of pre-historic years, and the long dark night of ignorance and superstition that succeeded, yet these silent monuments of the long ago display to our wondering vision, great nations and races of people, inhabiting widely remote portions of the globe, possessing various types and phases of civilization and different characteristics of mind, which distinguish their descendants of today. But whence the different races of mankind had their birth, and through what cycles of time they have been developing their growth; where, when and how they lived, are questions which receive no response from the annals of history, the voices of tradition or even the revelations of inspired prophesy. Difficult, in deed, is it to wander through the mazes of discussion, and the no less intricate mazes of diversified opinions, which but bewilder the investigator; and though fascinating as the field of research has been, still nothing offers so wide a scope of conjecture as that which the antiquarian finds in studying the ruins and relics of that people who centuries ago inhabited the North American continent.

But while these researches and discoveries throw but little light upon the origin or the character of its early inhabitants, yet reveal enough to conclusively prove that a race existed upon this continent ages ago, who possessed a knowledge of many of the arts unpracticed and seemingly unknown by the natives when discovered by the Europeans. With many it has been a cherished theory that the inhabitants, who first peopled the Western continent, came by land at a period when it was united by a bond of union with the Eastern continent, afterwards ruptured by internal commotions and upheavals, was severed from and into a distinct continent. But from what part of the world, at what period, or by what means they reached this country, can only be conjecture; but that the emigrants were a partially civilized people, and to a large extent an agricultural people there not good reasons to believe, nor can it be successfully disapproved. The art of the North American Indians of the last two or three centuries is said to be the exact equivalent, in point of advancement to that of Europe and the Orient of the stone age. The amount of material is limitless and corresponds remarkably with that found in the very substratum of those localities where man seems to have first begun his ascent towards civilization. Many of the scientists of the present day seem inspired to activity by the knowledge of the fact that the North American continent affords the best opportunity the world has ever known to study the be ginning of those things which constitute human progress an opportunity which by the encroachment of civilization is rapidly passing away.

It is said that, already upwards of 15000 specimens of the handiwork of the “Mound Builders,” the study of which, in connection with the survey of the mounds themselves and their surroundings, is gradually leading to a solution of certain archaeological riddles, which but a few years since appeared insolvable. Under the new light the mysteries, which have attached to the mounds and to their unknown builders are thought to be disappearing to a great extent, but only by exchanging conjecture for truth.

Be that as it may; this truth, that the present North American Indians and their ancestors have inhabited this continent during a period embracing ages of the past, none will deny who have studied and made themselves acquainted with the many existing facts; and that, from all that has been gathered, it is much more conclusive that the mounds were erected by them, than that they are the works of some long extinct race of people entirely different from that of the Indians. Therefore, let “Requiescat in pace” be the epitaph of the mound question for ail future to come; and also, let this, age of sentimentality, sensation, and the love of the marvelous come to an end, at least, upon that subject, that it may seek other fields for the gratification of its seemingly incomprehensible thirst for a knowledge of that which never existed. All Nations, both civilized and uncivilized, have long lost the memory of their barbaric state; and only traditions, here and there, speak of the ancient past. All mankind, in every age of the world have been mound builders; and the same principle that leads to the erection of mounds still exists in human nature. The various modern monuments of today are but ways of memorizing events which in ages past would have led to the erection of mounds.

Yet mournful to the contemplative mind are the records of departed greatness. These few still existing mounds of other ages, these dumb oracles of the pre-historic past, standing as monuments on the pedestal of years, point also to the ruins of earth s other empires, and call to her most potent nations with a voice more impressive to the heart than the tongue of a Tully; more symphonious than the harp of Homer; more picturesque than the pencil of Appelles, saving: “In us, behold-thine own destiny, and the doom of thy noblest achievements, the mutability of all human greatness and all human grandeur;” and around and before us, whose wild and hurried life precipitates the hour of our own dissolution, are strewed the crumbling fragments of an empire, equally as extended as those of the east; but the setting sun sheds its last ray upon their tumbling temples once hallowed by the footsteps of worshiping thousands, and the mellow moonbeams glimmer through the moss covered walls and gloomy galleries, now nearly gone to decay; their sanctuary is broken down, their glory is departed forever, and the generations hence, in viewing the mounds of their sepulture, will inquire with wondering thoughts what manner of beings they were.

How must the hearts of the remaining few Indians throb with anguish as they contemplate the destruction of their race and the gloomy destiny of their own children? With what swelling hearts must they survey the once extended boundaries of their empire! Alas! The grief of year’s en shrouds their souls, as they bow the knee of meek submission to the Great Spirit. Unhappy people! Who can but weep over the ruined hopes of your declining race! It is a truthful saying, that, human happiness has no perfect security but in freedom; freedom, none but in virtue; virtue, none but in knowledge; and neither freedom, virtue nor knowledge has any vigor or immortal hope, except in the principles of the Christian faith, and in the sanctions of the Christian religion. The birds that droop their plumage in the cage pine for the open field and flowery grove, where they may sing their songs of joy and lave their pinions in the free light of heaven. The vilest reptile that crawls upon the earth, the noblest beast that roams the forest flies in terror from its tyrant or repels the oppression that would deprive it of its freedom. So man naturally sighs to be free. Still tyranny, that demon of desolation, has stalked over the world for ages and bound in cruel bondage the noblest of the earth, and still in this 19th century of boasted freedom seems to be again emerging, like the phoenix, from the dust of ages. Alas! What is man, or a race of men, whose neck is beneath the foot of the despot?

Bishop Whipple of Minnesota says: “Some years ago an Indian stood at my door, and as I opened it he knelt at my feet. Of course I bade him not to kneel. He said: My father, I knelt only because my heart is warm to a man who pitied the Red man. I am a wild man. My home is 500 miles from here. I know that all the Indians east of the Mississippi river had perished and I never looked into the faces of my children that my face was not sad. My father had told me of the Great Spirit, and I have often gone out into the woods and tried to talk with him. ” Reader, here was a human being traveling 500 miles to learn of God; yearning and striving for a knowledge of the worlds Redeemer, but to whom and his race we have given powder and lead instead of the bread of life with our war-cry No good Indian but a dead Indian. ”

Alas! That it should be a principle of mankind to hate those they have wronged even as dogs rush upon one of their number that has been shot and not instantly killed and, rendered ferocious by his cries, tare him to pieces. Unhappy race! Amid the protracted woes of thy present life how can you forget the fearful history of thy past the hunger and thirst of the heart and the fire and frenzy of the brain!

Ah, when I look around over the wretched lives of the present feeble remnant of the Red Race of this continent, and then contemplate them as I knew them seventy-five years ago, I can but say: Each life is a woe! Truly, fearful and rugged has been their path of life from freedom and bliss to slavery and woe so replete in strife, confusion and death uttering their last groan in the wail of final despair; while the quality of confidence is now an utter stronger to their hearts; for they have experienced enough to harden them against the White Race of the entire world. They now realize that they are beyond the regions of all hope; vet they seem to yield to a certain exterior resignation to their fate. The world has lost its poignant interest in them; it is now a pageant upon which they are looking for the last time while indifferent to lift a hand to stay it in its course, even had it been within their power. Though, at times, they rebelled at their fate, and a wave of resistance swept over them, as with one hand they carried the woes of the present and, with the other, held up the glowing lamp of the romantic past; but a sense of its unreality told them that they grasped at a substance to find a shadow. The coming of one event changed even the atmosphere; at one moment their breath is a new and invigorating hope, the next, parched and dead. They see a covetous eye, a hated face. Their lips are apart; their teeth are set and their brows knit with the force that they summon to their souls to endure, as all now are but memories far off amid the shadowy past.