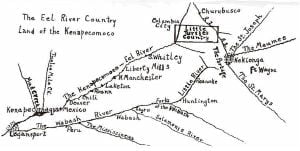

Here we must pause to note a difference of opinion as to the exact location of the Turtle’s Village. Calvin Young in his very interesting book on Little Turtle has attempted to show that this village was in the northeast part of Whitley county, northwest of Blue River Lake, where Blue River divides that lake from what is known as Little Devil’s Lake. He produces good evidence to show that there was an ancient Indian village on that favorable spot. Blue River is a tributary of Eel River and that would harmonize the many references about the Turtle Village being on Eel River. However the old settlers of this community received word directly from the Indians as to this location. Kilsoquah, the granddaughter of Little Turtle, who remembered both her grandfather and the location of his village, has told to some who are yet living that the Turtle’s village was at the bend’ of Eel River. This would seem to be almost unquestionable evidence in favor of this place. There is no doubt about their having been an important Indian village at Blue River Lake. There was also another at Tri Lakes. These villages were closely connected with the Turtle’s village and no doubt he was there frequently. But there seems to be no question about the Butler farm being the location of his ancestral home and the More farm the Eel River Post, the place of his residence in his last years.

The Passing of Turtle Village and Eel River Post

With the death of the Turtle the Miami Indians lost their great counselor. They took sides with the British in the. War of 1812, but were defeated by Gen. Harrison at Fort Wayne and other places When Harrison took possession of Fort Wayne, like La Baume and Harmar before him, he next turned his attention to the Eel River Indians. He sent Col. Simrall with a small army to destroy the Eel River Post and other villages on Eel River. He gave orders, however, that the house that the government had built for Little Turtle should be spared. So great was the respect for this great Indian chief that though he was dead, his home was to be respected and saved. Col. Simian obeyed orders effectively. He destroyed the Eel River Post village, sparing only the home of Little Turtle. He went on down the river and destroyed what was left of the old Turtle village. The Indians fled down the river and he followed them. At what is known as Paige’s crossing, where now the road running east from Columbia City on the south side of the Pennsylvania crosses Eel River and branches in three directions, Col. Simrall decisively defeated the Indians. Coesse, who was then a boy, later told of seeing the river run red with blood and filled with bodies, among whom was his father, Katemongwah, the youngest son of Little Turtle. Another village farther south, near what is now the Compton church, was perhaps destroyed at this time. With the destruction of these villages Indian power and resistance along Eel River came to an end. Their power and almost their very existence passed away with the passing of their great chief who had made the name of the Eel River Miamis known and feared not only in this great Northwest Territory but throughout the whole United States.

The Island

One other point of interest remains to be described in this part of the Eel River valley. About two miles south of Columbia City the new pavement on route 9 crosses Eel River. Just south of the river there is an elevated piece of ground known in an early day as “The Island.” The older residents there today know that their farms were originally a part of the Island. In Indian days it comprised some three hundred acres of land. It was bounded on the north by Eel River along which there was a high bluff. On the west and south it. was bounded by Mud Creek and swampy land. On the east and south it was bounded by swampland. The whole made a real island where the Indians could retreat with safety and could easily defend themselves from their enemies.

There is considerable known about this Island and many traditions relate to it. As early as 1771 the English commander at Fort Wayne told about a visit to the Indian village at this place. There he witnessed a green corn dance and ‘other interesting events. The Indians had a tradition that whenever they saw a white man riding a white horse across the Island, ‘some great disaster would follow. The Indians used this place as a fortress and a frontier military- post. Their enemies were not so much the white men as the Potawatomie Indians. It is well known that from here on west, the Kenapocomoco was the dividing line between the Miamis and the Potawatomies. The latter had made their inroads into the lands of the Miamis from the northwest. They had occupied the lands. as far south as Eel River and as far up the river as the Island, where Blue River enters from the north and Mud Creek from the ‘south. Here it would seem that the Miamis made a determined stand. Here the opposing tribes had a great battle in which the Potawatomies were at first victorious but were later defeated when Little Turtle came dawn the river with help from the upper Miami villages. It is said that as long as Little Turtle was active chief he kept a garrison here to ward off attacks from the Potawatomies.

The Beaver Reservation

West of Blue River along the Kenapocomoco, the Indian chief, Beaver, received as a reservation five sections of land by the treaty of 1826. The northeast section a this reservation extended to the present site of Columbia City. The old chief must have stood well with the white people for when Columbia City was named in 1854 there was considerable sentiment to call the county seat of Whitley county “Beaver.” It was finally settled by a popular vote in which the name ” Columbia City ” won by a very few votes. The Beaver village was near the river somewhere on the reservation. The village was never prominent, due partly to its insecurity from its Potawatomie neighbors. Old settlers have pointed out a number of places where groups of Indian cabins and wigwams stood in this community.

Down the Kenapocomoco

Below “The Island” Eel River becomes larger due to the confluence of Blue River and Mud Creek. But due largely to the conflict of the Miamis and the Potawatomies at this dividing line, there were few important Indian settlements below. For more than sixty miles down the river there was no permanent, important Indian village. But the early description of Eel River indicates that the river and the land through which it flowed were very important to the Indians and early white traders.

The river itself formed an important highway between the Eel River Post above and the important Indian settlement near the mouth of the river, and on to the Wabash settlements below. Along its banks were Indian trails. When war was not on between opposing Indian tribes the Indians and French traders used this river and its trails to go from the Eel River Post to the Kenapocomoco Village, some 75 miles below. The Indian canoe and the white man’s pirogue were frequently seen upon its waters. The long single file march of Indian ponies and their Indian riders often followed its winding trails. There is no doubt but that the great Little Turtle often made this trip. There are accounts of early French traders who went by this important route.

Early writers tell us that Eel River, the Kenapocomoco, flowed through a land of majestic grandeur. There were forests of oak, walnut, sycamore, maple, hickory and other varieties. There were plenty of nuts: hickory, walnut, hazel and pecans. The Indian was very fond of maple syrup and here, if he would, he could make all he wanted. There was an abundance of wild berries: raspberries, gooseberries, dew berries, straw berries. The Indian squaws often dried an abundance of these. One writer says that Eel River was a scene of unparalleled beauty. Wild flowers were everywhere and its flowerbeds covered thousands of acres with blossoms of every hue blending with wonderful color. Besides its rich flora, there was an abundance of wild animals.

Deer were to be found everywhere. In earlier days where the forests were not too thick the buffalo might occasionally have been seen. But fur-bearing animals of many varieties were plentiful. Of these the beaver was the most important. But there were the bear, raccoon, lynx, fox, wild cat, etc. This made the Eel River country an important hunting ground. The furs of these animals were taken up to the Eel River Post and from there by portage to Kekionga and then on to the east.

Indian Settlements on the Kenapooomoco

So much of the Eel River country was an Indian hunting ground rather than noted for important settlements. Only a few settlements can be located today. Just east of South Whitley where Spring Creek enters Eel River there was an important Indian village. George Croghan who came up this Kenacopocomoco in 1765 visited this village. He was received with unusual cordiality and given plenty to eat during the time he was there.

Northeast of the present town of North Manchester, almost on the present site of the Manchester College athletic field, was an Indian village, on the farm now owned by Harvey Cook. When Richard Helvey the first white settler in this part of the country, came here in 1834 he made his home on the site of this old Indian village and burying ground. Prom all that we can learn the name of the old chief was Pierish. He had a double log house with a fireplace and when he died he was buried just outside the house, somewhat under the base of the fireplace. He seems to have been an important person in the treaty of 1826. This site on Eel River was well chosen on a western bluff, where the river makes an elbow bend and where formerly two good springs flowed from the base of the bluff. Just across from North Manchester on Pony Creek was a temporary settlement of Miami Indians, though little is known about them. Pony Creek was so called because along its banks, where grass grew abundantly, Indian ponies were wont to come for pasture.

One mile below Roann, at the old village of Stockdale, on the north side of the river, near where the present mill stands, there was an old Indian village known as Niconza, or Squirrel’s village. Niconza was the Potawatomie word for Squirrel, and so we had Squirrel Creek and Niconza post office named for the same chief. Tradition says that the old chief himself was a Potawatomie but that he married a Miami squaw. So when the Potawatomies had to leave here in 1834, Niconza was given land down on the Big Reservation south of the Mississinewa River. Old Squirrel is known to have had a village on the Pipe Creek below the present site of Bunker Hill.

On the south side of Eel River, opposite the present Chili, there was a Miami village with a Captain Flowers as chief. His Indian name was No-ka-me-na. He was said to be a very fine looking Indian. After the treaty of 1834 he and his band had to move south of the Wabash. He was murdered by a lame Indian, an enemy, near Logansport, February 24, 1835.

One hundred years ago, 1834, Richard Helvey was the first white man to make a permanent settlement near North Manchester. He made his home on the site of the old Indian village. The above picture shows the Harvey Cook homestead that stands on the same spot where the Indian and pioneer homes stood. It joins the Manchester College athletic field, a part of which is shown in the picture. Here no doubt the Indian braves of long ago held their games and athletic feats. Across the college campus grounds, Indian trails led down the Kenapocomoco. Farther north beyond the Cook homestead was the old home of Judge Comstock, one of the prominent pioneers of that day. On that ground, now owned by Charles Comstock, along the present road to Liberty Mills, Indian squaws raised the first corn in this country.

There has been a remark able change in one hundred years from the Indian wigwam and the pioneer home to Manchester College and the beautiful little city of North Manchester.

Just below Denver, where Wesaw Creek enters Eel River, there was a Potawatomie village of some importance. An old chief by the name of Wesaw held a reservation here for a few years. Another Potawatomie chief by the name of Ashkum took an active part in a number of treaties made with the United States. The Potawatomies had to move west of the Mississippi after the treaty of 1834.

It is not the purpose of this booklet to deal with the history of white settlements along this route. South Whitley early became an important trading place. Its early name was Springfield and as late as 1867 Springfield Academy was founded and continued for a few years Collamer was at first called Millersburg, until later it was learned that a town in Elkhart county had the first right to that name. Liberty Mills was an early rival of North Manchester for the trade of this part of the country. It was connected with Huntington by an old plank road. An Odd Fellows lodge organized at Liberty Mills in 1850, was called Meshekunnoghquoh Lodge, in honor of the great Chief Little Turtle. The covered bridges at Liberty Mills, North Manchester, Laketon and. Roann are relics of by gone days hut they are still serving the public well. Old mills were erected on Eel River at South Whitley, Collamer, Liberty Mills, North Manchester, Stockdale, Chili and Mexico but only two or three of these are used any more. For further history the reader is referred to county or local history.