The marsh and swamp area of tidewater Virginia is extensive. For many miles both banks of the rivers are bordered by lowlands, which are inundated by the tides. In nearly all the rivers this occurs as far as 60 to 70 miles from Chesapeake Bay. Some of these tracts are marshy flats covered with a growth of dock, rushes, and cattails. Others are overgrown with virgin forests of cypress, swamp oak, swamp gum, maple, and red birch. In the picturesque vernacular of the region such are called “low grounds.” In some places the swamps extend continuously from one to three or four miles following the windings of the river, and reach from a quarter of a mile to a mile and a half back toward the higher ground. The swamps provide cover for consider-able game, and it is in these fastnesses that the Pamunkey of today, as they did of old, pass much of the time in gaining a livelihood. The marsh flats provide feeding and roosting grounds for hosts of wild fowl which engage the attention of the Indians during the migration periods.

The Virginia deer have survived as the last of the big game on the Pamunkey river, and some old deer-hunting practices have continued to the present time. The passing of the bear and beaver, however, dates back earlier than the memory of the living generations. Yet the bear lingers with surprising persistence in the Great Dismal Swamp on the line dividing Virginia from North Carolina. This imposing wilderness, however, is too far from the haunts of the Pamunkey for them to know much about it in these days, though the Nansamond Indians, inhabiting its western and northern margins, have something to offer in respect to bear hunting. We may infer some similarity to have marked such practices among the different town-tribes of the Powhatan area. The bears of the Dismal Swamp hibernate for only a short period, if at all; some say for about six weeks. They secrete themselves in large hollow trees to sleep. In the fall and early winter the Nansamond seek to kill them because they are fat. The bears resort to the gum groves in the swamp to fatten on gum berries. They may there be heard at a considerable distance breaking off the branches. Then the hunters approach closer stage by stage, moving forward when the animal is unable to hear them because of the stir he himself is creating. The Nansamond, however, like to search for the hibernating bears, as, incidentally, do most of the Algonquians. This tribe undoubtedly has some reliquary customs and beliefs concerned with bear hunting still to be recorded. To my own knowledge they have the custom of cutting off a bear’s foot and fastening it over the house door; one reason being as a luck-trophy. Another interesting hunting practice is remembered by Nansamond wolf trapping by means of a pit. We turn back, however, to the characteristics of Pamunkey life; the other is for separate treatment.

So much do the marshes and swamps engage the attention of the natives that they may be safely said to furnish the influencing factor in the economic life of the Chesapeake tribes. I shall have occasion shortly to refer to the Indians’ familiarity with the conditions of mud which surround them on every side in their hunting and fishing occupations. The common geographical features of eastern Virginia really have to be understood before the ethnology of the tidewater tribes can be evaluated. It might be added that in the opinion of the Indians there has been a slight sinking of some of the river flats within memory. Today Cherrycook marsh, a few miles above the reservation, is a ”duck and fur” marsh, where at high tide a canoe can be shoved with a pole. This condition extends back some 30 years. Estimating from facts obtained by Chief Cook, one concludes that about 1820 the same land was dry and was cultivated in wheat and corn by the father of Dr. John Braxton, a planter who owned this land.

I might repeat that hunting is still a part of the daily occupation of most of the Pamunkey men, whether or not they be the proprietors of the rented portions of the swamp. The daily fare is derived largely from the chase in one form or another. In the fall, winter, and spring almost every day wild meat is consumed on the reservation. The hunters are abroad during the early morning hours either in the swamp to pick up muskrats, raccoons, or opossums, or on the river to get chance shots at ducks. Subsequent to these early-morning excursions they lie about the house and rest until nearly noon, while the women are dressing and cooking the meat. Then comes the noonday meal, the first real one of the day. Time has indeed brought little change in the eating habits of these Indians, and, we might also infer, in their domestic habits.

The numerous and far-flung ox-bows of the tidal rivers bounding the marshes and swamps make the distances by river much greater than by land. For instance, the distance from Pamunkey town to West Point, which lies at the junction of the Mattaponi and Pamunkey rivers, is nine miles by land, but following the windings of the river it is more than thirty. The windings of the Mattaponi just across from the Pamunkey are correspondingly tortuous. From West Point again to the Mattaponi Indian town it is twenty-three miles by river, but ten by land. The Mattaponi is navigable for small tugs, and a small freight and passenger steamer, the Louise, plies a route twice a week for forty-two miles. The configuration of this whole region is admirably shown on Captain Smith’s chart of 1612. It is actually still serviceable for the navigation of the Mattaponi River. By comparison with recent Government charts, every bend, every marsh, and even the location of the early village-sites marked on Smith’s map can be ascertained.

In gaining their subsistence upon these extensive lowlands the ancient Indians are credited, through tradition, with having effected some physical changes in the country which are not a little interesting since no other record of such achievements seems to have appeared in print. These are the canals, or ”thoroughfares,” as they are yet called, some still in existence and pointed out as having been conceived and dug by the aborigines. The value of one of these ditches cut across some marshy neck where the river doubles on its course may well be appreciated by any one journeying by water through the country. For instance, at Cohoke “Mow-ground,” just below the present reservation, there is a short ditch cutting across a narrow strip of marsh, believed to have been done by the Indians.

This thoroughfare shortens the distance not less than five miles in ascending or descending the Pamunkey River. It remains in use today, without modification or enlargement at the hands of the whites, according to local statement. There is a similar one at Hills marsh, lower down the river, opposite the site of Old Uttamussak where Powhatan had his sanctuary. This thoroughfare is marked on Smith’s map. It is now much obstructed, though still open to canoes. In one of the accounts of his exploration Smith referred to this short-cut which he thought to be of natural origin.

It would be interesting to investigate these artificial works, if all of them are such, to ascertain their origin. Similar ditches and log bridges, evidently the beginning of engineering enterprise among the Indians of the region, occur at other points in the Chesapeake area, and even on the Eastern Shore in the Nanticoke country.

I have mentioned the Pamunkey necessity of knowing how to manage themselves when obliged to proceed over areas of mud. The Indian hunter of the Chesapeake country operates in a region where, without experience in judging the supporting quality of mud and knowing how to wade or crawl in it, he would be lost. When hunting, the Indians some-times become stranded on a marshy island separated from the shore by mud-bars; or, to secure game that has been brought down, it may be necessary to wade a hundred feet through mire of unknown depth. Or still, in making their hunting excursions in marshes or swamps at some distance from their boats, a lagoon, or ‘gut,” showing only a surface of brown slimy mud, may have to be traversed to reach one of the deadfall sets. Even to render aid to some less experienced sportsman, mired perhaps to the armpits, the art of self-navigation in mud is essential. The Indians recognize two kinds of mud the moderately firm and the ”floating” mud. The former may be traversed by an experienced man if care is taken not to allow the weight of the body to remain more than an instant upon each leg, not to put the foot straight downward in the mud, but to proceed on flexed lower limbs, the weight carried on the shins. Should the mud be softer, of the floating variety, it may be necessary to advance prone on the belly in ”turtle fashion.” Movement must be continuous lest the body settle too deep to be worked loose. Children at an early age learn this art. They help their parents retrieve ducks which have been shot out on the mud-flats. In short, the tidewater Indians throughout grow up with such experience at their elbows.

Captain John Smith in his day observed the expertness of the Indians in traversing the mire:

The Indians seeing me pestred in the Ose, called to me: six or seven of the Kings chief men threw off their skins, and to the middle in Ose, came to bear me out on their heads. Their importunacie caused me better to like the Canow than their curtesie, excusing my deniall for feare to fall into the Ose: desiring them to bring me some wood, fire, and mats to cover me, and I would content them. Each presently gave his help to satisfy my request, which paines a horse would scarce have indured: yet a couple of bells richly contented them.

The Emperor sent his Seaman Mantivas in the evening with bread and victuall for me and my men: he no more scrupulous then the rest seemed to take a pride in shewing how little he regarded that miserable cold and dirty passage, though a dogge would scarce have endured it. 1

Besides stalking the deer to kill them, the Virginia Indians seem to have resorted extensively to the drive. One of the earliest references to the customs of these tribes is the description of a drive by the Pamunkey in Chickahominy swamp, on which eventful occasion Captain Smith was surprised and taken captive. Three hundred men were supposed by him to form the company. We also hear of employing fire in conjunction with the deer drive, a custom in itself suggestive of southern influence. The deer drive as practiced by the Indian remnants in the state today, and their white neighbors as well, is as follows:

The party of hunters is divided into two crews. One is to occupy boats at stations in the river where they are to wait for the deer to be driven out of the swamp to be shot, the other is obliged to plunge into the swamp with dogs and drive the game toward the river where the animals will be intercepted in their traverse. The method of selection, to be impartial, is as follows: To assign the crews their appointed tasks, the chief or captain holds in his hand as many sticks as there are men on the drive. Half of the sticks are shorter than the others. Each man then draws a stick. Those drawing the “shorts” may remain in the boats, while those drawing the “longs” are to form the driving party.

It need hardly be added that the Pamunkey deer hunt is an exciting and noisy event.

Deer are fairly abundant in the “low grounds” up and down the middle course of Pamunkey river. For instance, at one place just below the reservation, known as Cohoke “low-ground,” in the winter of 1922 when the river rose, more than thirty deer were seen in one day to swim the river, making for high land to escape the inundation of their haunts.

An event of importance is the annual deer drive at Pamunkey when the hunters secure the venison which they carry to the Governor’s house in Richmond in fulfillment of their treaty obligations to furnish yearly tribute in the form of flesh, fur, feather, and scale. The Pamunkey are justly proud of the fact that they have performed this duty without a break since the adoption of the treaty between them and the General Assembly.

The episode of Captain Smith’s capture and at the same time his description of the deer drive of that day are interesting enough to deserve reproduction.

At their huntings in the deserts they are commonly 2 or 300 together. Having found the Deare, they environ them with many fires, and betwixt the fires they place themselves. And some take their stands in the midst. The Deare being thus feared by the fires and their voices, they chace them so long within that circle, that many times they kill 6, 8, 10, or 15 at a hunting. They use also to drive them into some narrowe point of land, when they find that advantage, and so force them into the river, where with their boats they have Ambuscadoes to kill them. . . .

In one of these huntings, they found Captaine Smith in the discoverie of the head of the river of Chickahamania, where they slew his men, and tooke him prisoner in a Bogmire; where he saw those exercises, and these observations. 2

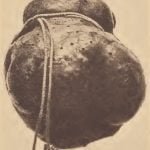

Hunting the “sora” rail (Porzana Carolina Linn.) in the autumn has been an important occupation among the river tribes of Virginia from time immemorial. In earlier days the birds appeared on the Pamunkey marshes in swarming flocks. Even now they are abundant enough to furnish a profitable pursuit to the natives during the periodic flights. The sora at these times cling to the brackish marshes. The old Pamunkey had, accordingly, a most interesting legendary belief, namely, that the sora arose from the marshes as metamorphosed frogs. And they know that the frogs develop from tadpoles. One of the reasons given for thinking the sora evolve from frogs is that the birds have partly webbed feet like the frogs. We may imagine, I suppose, that the nocturnal migrations of the bird have been responsible for ignorance of the actual conditions. A poetical fancy has associated the disappearance of the myriad croaking frogs from the marshes in the fall with the appearance of the myriads of birds during the season just following and filling the same places with their cries. They come about September 20th. As to the method of killing sora the old native practice has with little modification survived until today. The birds roosting at night in their marshy domain are invaded by the hunters in canoes, poled with the long paddle. The boats carry a beacon light at the bow to ”light up the marsh” and blind the birds so that they can be struck down into the water from their perches on the stalks of the rushes or hit with the paddles as they fly in commotion toward the beacon. They are then gathered and piled into the boat. The beacon itself is an interesting object. Tradition says that the ancient sora beacon, which is called a ”sora horse,” was an openwork clay basket. One of these, made about 1893, is figured by Holmes in his ceramic study. 3 In latter days the ”sora horse” or fire-basket has been constructed of iron strips (fig. 52). The specimens shown are from the Chickahominy.

Pollard 4 says something about the custom of sora killing at Pamunkey in his day.

In the autumn sora are found in the marshes in great numbers, and the Indian method of capturing them is most interesting: They have what they strangely call a “sora horse,” strongly resembling a peach basket in size and shape, and made of strips of iron, though they were formerly molded out of clay. The ”horse” is mounted on a pole which is stuck in the marsh or placed upright in a foot-boat. A fire is then kindled in the ”horse.” The light attracts the sora and they fly around it in great numbers, while the Indians knock them down with long paddles. This method is, of course, used only at night.

The present Indians refer to sora hunting as ”sorassin.” This term is most interesting because it may be a corrupt derivation from the native Indian term. The final element {-assin) occurs in Massachusetts Algonquian wikwassin which denotes fishing by torchlight. The very name sora itself is a puzzle. Undoubtedly its origin too is Indian, though whether it comes from the tidewater Algonquian term or from some other southern language it would be difficult to say merely through an attempt to etymologize the word.

The Pamunkey, Mattaponi, and Chickahominy hunt in the swamps along the rivers by stalking raccoon, opossum, and muskrat for their meat and fur, mink and otter for fur alone. Rabbits, wild turkeys, doves, quail, meadow-larks, robins, flickers, cedar-birds, snow-birds, and even the “bull-bat” or night hawk are hunted and eaten.

Powhatan Trapping

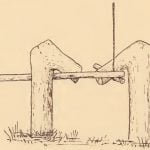

The business of trapping is, however, most interesting to us because the old-fashioned Indian deadfall is yet almost exclusively operated. The reason for its survival in competition with steel spring-traps is that the hunters have been convinced of the superiority of the old-style fall which does not rust, which costs nothing, and which kills and holds the animal without tearing its hide or allowing it a chance to gnaw off its foot and escape. Raccoons, opossums, and muskrats are regularly taken in the stationary deadfalls, which are permanently built at places where the animals come to the water to wash their food or to forage. Some of the deadfalls pointed out today are known to have been constructed not long after the Civil War. Their “pens” are still intact. Again, many of the deadfall sites are known to have been occupied continuously since those days. Caked with mud at low tide, it seems that the timbers are almost indestructible. Figs. 47 and 48 show the situation of several of these along Great creek on hunting ground number 3 at Pamunkey. Figs. 53 and 54 show the plan of construction of the Pamunkey deadfall. It corresponds precisely with what is employed among all the river tribes of the tidewater country.

Several outdoor practices surviving from the serious days of hunting and fishing portray the customs of old Pamunkey life. For instance, when overtaken abroad by night through any of the mis-chances which are apt to impede them while traveling on the river, they have resorted to the stems of wild honeysuckle for fire-kindling material. No matter how wet the weather, and it is nearly always wet or humid in the Virginia low country, a blaze may be started with these stems. Their use corresponds to the highly inflammable birch-bark used by the northern Algonquians at all times in the camps. Some folklore clusters about fire-making. They have taught them-selves not to burn sassafras or grape-vine either indoors or out, the reason being that they fear some-thing will happen to their livestock, although what the connection is we are unable even to imagine. The hearth must not be cleaned after dark. The fire-logs may be pushed together, but not turned, to make them flame. A crackling fire in winter denotes snow for the ensuing day. When soot, accumulating on the chimney-back, sparkles and glows, making what the white settlers called “chimney lice,” the Powhatan say, “Fresh meat will be had tomorrow.” This sign is believed in by all the Virginia bands.

The Pamunkey know well the old custom, so widespread among the Algonquians, of sharing the first game killed by a little boy among the father’s friends. The boy moreover was not supposed to partake of the meat of his first game. The tusk of a boar is considered worth preserving as a fetish to produce strength. The penis-bones of the raccoon and mink are also kept to insure luck to hunters, and the metacarpal bone of the deer serves a similar function as it does among the more northerly Algonquian hunters.

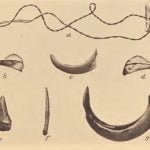

The bows used by the Virginia tribes of early times are described as made of witch-hazel. At present this is not known to the descendants, though bows of hickory and oak, from three and a half to five feet long, are not uncommon. Information shows that the ”sap-wood,” not the heart, of the white cedar was also used. Bows are sometimes square in cross-section, sometimes convex on the inside and flat on the outside, with pointed ends. Frequently the middle third of the bow staff is thicker than the outer thirds, which form is called ”buzzard wing,” suggested by fancied resemblance to a buzzard in flight. Arrow shafts of ”arrow-wood” cut from natural twigs, as of old, are still known, as well as others split down and smoothed from heart of oak. Several specimens of feathering, two turkey feathers being used. Occasionally the Pamunkey mount stone arrowheads found in their fields upon such shafts, fixing them with a cord or a mulberry-bark wrapping in a way which cannot be much differ from the method of several centuries ago Specimens of these figs. 57, 58. The arrow is turned loose from the right hand by the widespread Algonquian primary release. Passing reference should be made to the cross-bow in the Virginia tidewater area where its introduction by its introduction by Europeans among the Indians of colonial times parallels what happened northward as far as the Montagnais-Nascapi. The Virginia Indian type of this curious toy is shown in fig. 59. It is reported among the mixed Indian groups as far south as the Carolinas.

A tradition is related by the Mattaponi concerning the poisoning of arrow heads by their ancestors. It is said by Powhatan Major there that the stone arrowheads with a flat side, and especially those with corrugated edges, were intended to carry a poison made from rattlesnake venom-glands mixed into a paste. The corrugated arrowheads of white quartz answering to this requirement are relatively abundant in the tidewater region. While traditions of former economic properties should not be totally ignored, one feels nevertheless highly skeptical about their sources.

Powhatan Hunting Photos

Citations:

- Smith’s account of Virginia in Tyler, L. G., Narratives of Early Virginia, New York, 1907, op. cit., p. 58.[↩]

- Smith’s account of Virginia in Tyler, L. G., Narratives of Early Virginia, New York, 1907, p. 104.[↩]

- Holmes in Twentieth Annual Report Bureau American Ethnology, pi. cxxxvi.[↩]

- Pollard, J. G., The Pamunkey Indians of Virginia, Bull. 17, Bur. Amer. Ethnol., Washington, 1894, p. 15.[↩]