By Act of Congress of March 2, 1819, Arkansas Territory was established July 4, embracing substantially all of what are now the states of Arkansas and Oklahoma; though the civil government of Arkansas Territory was limited to that section lying east of the Osage line, divided into counties, and embracing approximately the present state of Arkansas. That west of the Osage line was the Indian country, and in later years became known as Indian Territory. James Miller 1 of New Hampshire was appointed the first Governor of Arkansas Territory, and among the duties of his office was that of supervision of the Indians within his jurisdiction.

After the battle at Clermont’s Town an effort was made to induce the warring tribes to enter into a treaty of peace. This was accomplished in October 1818, 2 in Saint Louis, in the presence of William Clark, the Governor of Missouri Territory. Directly after Governor Miller assumed his duties as executive, he was required to intervene between the Osage and Cherokee in an effort to prevent imminent hostilities growing out of the killing of a number of Cherokee hunters by a band of Osage under Mad Buffalo. In April 1820, Governor Miller departed from the seat of government at Arkansas Post, on his mission to the Cherokee and Osage. He was gone two months, and prevented temporarily at least – the threatened renewal of warfare by the Cherokee. He went first to the Cherokee settlements, where he sought to dissuade the members of that tribe from further hostilities by his promise that he would endeavor to secure from the Osage the murderers of their hunters. Accompanied by several Cherokee chiefs, he then ascended Arkansas River to the mouth of the Verdigris and visited the Osage town. He then induced representatives of both tribes to agree to meet at Fort Smith on the first of the next October, and return all prisoners and stolen horses.

The conference held at Fort Smith in October, however, did not restore peace. During the following December a band of Osage attacked a number of Cherokee hunters on the Poteau near Fort Smith. Four hundred Osage warriors accompanied by some of their Sauk and Fox allies made a hostile demonstration in May 1821, 3 against Fort Smith, then protected by only seventy men. They were on their way against the Cherokee, and in an insolent manner demanded ammunition, which was refused by the officers of the post. They threatened to attack the garrison, but being warned by the officers in command not to approach, and menaced by the cannon of the post, sullenly retired; and on their departure they killed three peaceful Quapaw, robbed several white families on Poteau and Lee’s creek, and carried off all the horses they could find. Soon after this occurrence a war party under Walter Webber killed a Frenchman named Joseph Revoir, 4 living fifteen miles above Union Mission, whose offense was that he, like many other Frenchmen, was living with the Osage, with whom the Cherokee said they would not make peace “as long as the Arkansas River runs.”

The continued insolence of the Osage, reprisals and turbulence by that tribe and the Cherokee, uneasiness of the missionary establishments and other white people, led to a change in the military policy of the Government; and in the summer of 1821 orders were given that the Seventh Infantry should be removed from Fort Scott and Bay of Saint Louis, and employed for the purpose of giving greater security to white people west of the Mississippi, of maintaining peace between the Indians, and of protecting trading expeditions to Santa Fe. Four companies of that regiment were assigned to increase the force at Fort Smith and six were sent to Natchitoches. In November of that year, two hundred fifty soldiers of the Seventh Regiment, under Colonel Matthew Arbuckle, 5 arrived at from Canadian River August 22, 1850, by Company D, Fifth Infantry, Captain R. B. Marcy, four officers and forty-eight men to protect from Indians travelers en-route to California. Store houses and huts were erected so that by December 1, the command were all under roof but the War Department did not approve the site and ordered it removed south near Washita River. On April 17, 1851, camp was struck and the command moved to a point on Wild Horse Creek.

The name of the veteran Arbuckle was conferred upon four distinct army establishments in Indian Territory. The encampment of the Ranger companies of Captains Boone and Ford during the winter of 1832 and 1833 was located one and one-half miles below Fort Gibson and on the opposite side of the river and was called Camp Arbuckle. A second Camp Arbuckle was established on Arkansas River at the mouth of the Cimarron, June 24, 1834.

Another Camp Arbuckle was established on the right bank and one mile the mouth of Arkansas River from New Orleans, on their way to Fort Smith, but having to wait for keel boats for their passage up the river, did not reach their destination until the twenty-sixth of February, 1822. 6 The remainder of the regiment left New Orleans on the sixth of November, 1821, under Lieutenant-colonel Zachary Taylor for the military post at Natchitoches on Red River.

When Colonel Arbuckle came to Fort Smith he superseded Major William Bradford, who had been in command there since 1817, and who went to Natchitoches; and from a small force of seventy men the garrison assumed a new importance which it maintained for two years, until it was removed farther up the river. The troops at Fort Smith had been compelled to subsist themselves, and Colonel Arbuckle found there a farm of eighty acres cultivated by the soldiers, with one hundred head of cattle, four hundred hogs and one thousand bushels of corn from the preceding year. The soldiers were not only obliged to raise from the soil the grain and vegetables they and their stock consumed, and supplement their larder with buffalo meat, but they were required to build their own houses.

The permanent Fort Arbuckle established April 19, 1851, on Wild Horse Creek near Washita River was at first built of logs to accommodate four companies and June 25, 1851, by general order number thirty-four the Adjutant-general named it Fort Arbuckle for General Arbuckle who had died the eleventh of that month. The Fort was abandoned February 13, 1858, and reoccupied June 20, 1858. It was then occupied until May 5, 1861, when it was seized by the confederates. (Reservation Division Adutant-general’s office, Outline Index, Military Forts and Stations, “A” page 376.)

The steamboat Robert Thompson from Pittsburg, arrived at Fort Smith in March or early April, 1822, 7 with a large keel boat in tow, loaded with provisions for the garrison. This was probably the first steamboat to reach Fort Smith. 8 Prior to that time supplies had been brought from Saint Louis in keel boats propelled by man power and sail. The detachment of the Seventh Infantry that Colonel Taylor had taken up to Natchitoches was removed in July farther up Red River near its junction with the Kiamichi, where in May, 1824, a post was established on a higher and healthier site and called Fort Towson. 9

The treaty effected at Saint Louis between the Cherokee and Osage in 1818, had not resulted in the peace that had been hoped for. With the establishment of the relatively large military force at Fort Smith in 1822, renewed efforts were made to remove the contentions between those tribes and compel them to cease their warfare. These efforts resulted in a new treaty of peace 10 between the Osage and Cherokee at Fort Smith on the ninth day of August, 1822. It was executed in the presence of “James Miller as Governor of the Arkansas Territory, commander in chief of the militia and Superintendent of Indian affairs,” and Colonel Matthew Arbuckle commanding the United States troops in the territory.

The treaty provided that the Cherokee were to return by the twentieth of the next month seventeen Osage prisoners still in their possession, conditioned that those who preferred to live with their captors might do so. It provided also that members of each tribe might pass from one nation to the other on the north side of the Arkansas, killing only such game as might be necessary to sustain life while traveling, but without the right to establish hunting camps in the land of the other tribe. The Osage granted to the Cherokee the right in common with themselves to hunt on the lands south of Arkansas River.

The treaty contained a formal declaration of peace and termination of the long war that had raged between the tribes. The execution of the treaty with the formalities that accompanied it, and the menace of the military arm of the Government to encourage its observance, brought relief and joy to the meagre white population along Arkansas River and particularly to the Mission School at Union, where the new turn of events presaged an increase in the attendance of Indian children. But while the war was over, the turbulent Osage continued to make trouble, and the troops under Colonel Arbuckle, operating out of Fort Smith, were constantly employed in policing the country. Hostilities and acts of violence at the hands of the Osage were frequent. Major Curtis Wilborn was killed on November 17, 1823, while hunting on Blue River, and the Osage were held responsible, but they refused to deliver up Mad Buffalo and others who were charged with the murder. It was reported in January, 1824, that the Osage, Cherokee, Kickapoo, and Delaware met at the mouth of the Verdigris and indulged in a dance which was characterized as a demonstration against the whites. Union and Harmony missions were disturbed, the white settlers along the Arkansas were becoming nervous and were raising volunteers.

It is not surprising then that in April, 1824, Colonel Arbuckle received orders 11 for the immediate removal of the troops from Fort Smith to the mouth of the Verdigris, where a new military establishment was to be erected near the Arkansas Osage, who would thus be under stricter surveillance of the troops. The site of the new garrison was said to be about eighty miles above Fort Smith, fifty miles below the Osage village, and at the proposed western boundary of Arkansas Territory, and the new move was believed to guarantee security to the western frontier.

When the troops arrived at their western destination in April, it was decided to locate the post on the east bank of Grand River three miles from the mouth, three or four miles from the Verdigris, and an equal distance from Chouteau’s trading house. The post was named Cantonment Gibson, in honor of the then commanding General of subsistence, George Gibson. Soon after the arrival of the troops from Fort Smith, another detachment of two hundred men from New Orleans arrived at Cantonment Gibson. The troops were quartered in tents and were immediately set to the task of erecting log cabins for the reception of public property; their own quarters were to be constructed later. By January, 1825, it was reported that works of defense and quarters for the soldiers were rapidly progressing, and that the latter were so far completed as to afford snug and comfortable accommodations for the officers and men attached to the garrison.

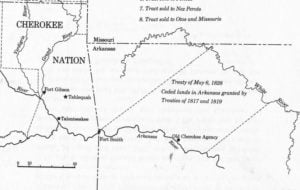

Congress passed an act May 26, 1824, locating the western boundary of Arkansas Territory forty miles west of where it had been, so that it included in Arkansas, Fort Gibson and all of Lovely’s Purchase. The line began forty miles west of the southwest corner of Missouri, and ran south to Red River. 12 It crossed the Arkansas and Verdigris near their confluence, and today would intersect the city of Muskogee.

Immediately after the passage of the act removing the boundary line farther west, the General Assembly of Arkansas on June 3, 1824, addressed a memorial 13 to the President, praying that he countermand the order prohibiting white settlers on Lovely’s Purchase, and asking him to permit its occupation; “the salubrity of the climate and fertility of the soil which distinguish this beautiful and interesting section of our country” presented strong inducements to emigrants who were rapidly settling it.

This request was strongly resented by the Cherokee, who claimed the use, if not the title, to Lovely’s Purchase, as an outlet westerly to the hunting grounds. The General Assembly adopted another memorial the next year on the subject, adding mention of the rich saline and mineral ores included within the forbidden land; but the Government promptly denied their requests on the ground of its duty to the Cherokee; this tract extended from the Cherokee land at the junction of the White and Arkansas rivers westwardly to the Falls of the Verdigris, and when surveyed by the Government was found to contain seven million three hundred ninety-two thousand acres.

Cherokee Treaty of 1828

The Government reaffirmed its intention of preserving this country for the Cherokee as an outlet to their western hunting grounds, qualified only by the reservation to the Government of the right to lease the salt springs included in the tract. Notwithstanding the position of the Government, in October, 1827, the Arkansas General Assembly presented to the President another and more forceful memorial, renewing their demands for Lovely’s Purchase, and without waiting for permission, on October 16, 1827, included the western part of the tract in a new county called Lovely County, 14 and proceeded to issue a commission to Benjamin Weaver, October 23, 1827, as Justice of the Peace for Lovely County, for two years. The seat of government of the county was fixed at a place on the west side of Sallisaw Creek thirteen miles above its mouth. Here a number of log buildings were put up and the place was called Nicksville. After the Cherokee treaty of 1828 was enacted the Cherokee, Colonel Walter Webber selected the place as the seat of his mercantile establishment. Webber in turn sold the improvements to the commissioners for Foreign Missions as the site for Dwight Mission which removed from Arkansas with the Cherokee and opened its school here the first of May 1830. 15 White people had been settling in the so-called Lovely county in such numbers that the government finally yielded to them. The correspondence on the subject terminated in an extended communication by the Cherokee, dated February 28, 1828, in defense of their rights. In reading this as well as the other documents on the subject, one is impressed with their dignity, moderation, diction, and cogent reasoning compared with which the arguments of the people of Arkansas made but a poor showing.

Accordingly, the Government entered into a new treaty with the Cherokee in May, 1828, by which the latter exchanged their lands on Arkansas and White rivers for seven million acres west of the Osage line, on which they were later permanently located and which became the last home of the Cherokee. This was bounded on the east by the western boundary of Arkansas, which was by the treaty of 1828, moved back east to where it was formerly located, and thus Lovely County was extinguished and became only a memory.

The new home of the Cherokee included the western part of Lovely’s Purchase, but a reservation was made to the United States of a tract of land two miles by six in extent on the east side of Grand River, for the military force established at Fort Gibson. The treaty contained a number of interesting provisions: Five hundred dollars was provided for the remarkable Cherokee, George Guess, or Sequoyah, for the great benefits he had conferred upon his people by his invention of an alphabet, and one thousand dollars was to be given the tribe to purchase a printing press and type, which would soon be employed in printing in their own language. In exchange for a saline which Sequoyah was operating in Arkansas, he was to be allowed the use of one on Lee’s Creek in the new country.

To induce the Cherokee east of the Mississippi to remove to the new home provided for them, it was agreed to give each head of a family who would so remove, a rifle, a kettle, and five pounds of tobacco, besides a blanket to each member of the family. Under this treaty, the Arkansas Cherokee soon began removing westward to their new home.

Before this treaty could be made, it had been necessary, in 1825, for the United States to enter into a new treaty 16 with the Osage was entered into at Council Grove on the Santa Fe trail, pursuant to an act of Congress of March 3, 1825, providing for making a road “from the Western frontier of Missouri to the confines of New Mexico.” By the treaty the Osage agreed to this road being marked through their country and promised not to molest the travelers going to Santa Fe.)) with the Osage, by which the latter ceded all the lands lying within or west of Arkansas Territory. This treaty, however, made provision for reservations on Grand River of one section each to a number of half-breed Osage, all bearing French names. The Chouteau reservations, being afterward included in the Cherokee domain, became the subject of controversy and were later extinguished.

However, the Creeks were the first to arrive in any number in the new country that was to be the home of the Five Civilized Tribes. They came in the shadow of tragedy that was the forerunner of others, marking the removal of thousands who followed them. In 1825, General William Mcintosh, a prominent member of the Creek Tribe, had been induced by the authorities of Georgia to sign a treaty 17 ceding the lands of the Creek Nation and agreeing to the removal of the tribe west of the Mississippi. The more conservative members of the tribe opposed this measure, and sentenced Mcintosh to death for his act, which was claimed to be in violation of the laws and against the will of a large majority of the tribe. The sentence was executed by a body of Okfuskee warriors who surrounded Mcintosh’s house and shot him and his son-in-law, Colonel Samuel Hawkins, as they tried to escape. 18

The signing of the treaty so enraged the great majority of the Creeks, and the killing of Mcintosh created such bitter feeling among his friends, that the latter determined to separate from the other members of the tribe and migrate to the country west of the Mississippi. This was authorized by the Government by a new treaty 19 of January 24, 1826, and provision was made by the Government to remove the Indians.

Colonel David Brearley

Colonel David Brearley, 20 who had been an agent to the Arkansas Cherokee, was appointed May 13, 1826, agent to the Mcintosh Creeks; and in April, 1827, Brearley came up the Arkansas with an exploring party of Creeks, who selected as their future home the country lying continuous to the mouth of the Verdigris. Brearley selected and purchased for an agency some of the buildings of Colonel A. P. Chouteau, used as a trading post, on the east side and about three miles above the mouth of the Verdigris. By November, Brearley had a number of the Mcintosh party enrolled for the journey, and the twenty-fifth of that month they arrived at Tuscumbia; in February, 1828, Brearley ascended Arkansas and Verdigris rivers in the steamboat Facility, with two keel boats in tow, having on board the vessels seven hundred eighty men, women, and children, who were landed at the Creek Agency. The Facility, probably the first steamboat to ascend the Verdigris, returned to New Orleans with a cargo of hides, furs, cotton, and five hundred barrels of pecans taken on at the Verdigris trading houses and points lower down the Arkansas. 21

Colonel Arbuckle, ever solicitous for the peace of the country, proposed a conference at the agency between the Osage and the newly-arrived Creeks, who were the first strangers from the east to come so far west to locate upon the land formerly claimed by the Osage. Clermont extended a welcome from his tribe, and mutual expressions of good will gave the appearance at least of an auspicious beginning for the new home.

Brearley returned in November with five hundred more Creeks, who joined the first arrivals in their settlement on the point of land between Arkansas and Verdigris rivers. Here, they were convenient to the agency and their rations, and under the protection of Fort Gibson; then it was not considered safe for them to venture to settle in the more remote districts where they would be in danger of attack by the western more warlike tribes including even their neighbors, the Osage, who could not be trusted. In the following August, five hundred more Creeks arrived and joined those who had preceded them. 22

Citations:

- James Miller was born in Peterboro, N. H., April 25, 1776; entered the array as major in 1808, became Lieutenant-colonel in 1810, and colonel in 1814. Distinguished in the battle of Niagara Falls for which he was brevetted Brigadier-general and on November 4, 1814, by resolution of Congress received a gold medal. Resigned from the Army June 1, 1819, to become the first governor of Arkansas. On December 26, 1819, Governor Miller reached the Territory on a keel boat from Saint Louis and assumed his duties as governor. He served until the latter part of 1824 when he was appointed collector of customs of the Port of Salem, Massachusetts, which post he held until 1849. He died at Temple, N. H., July 7, 1851.[↩]

- American State Papers, “Indian Affairs” vol. ii, 172.[↩]

- Arkansas Gazette (Arkansas Post), May 12, 1821, p. 3, col. 2. Niles Register (Baltimore), vol. xx, 298.[↩]

- Arkansas Gazette (Arkansas Post), July 14, 1821, p. 3, col. 1.[↩]

- Matthew Arbuckle was born in Greenbrier County, Virginia in 1776. He became second-lieutenant in the Third Infantry on March 3, 1799; as Lieutenant-colonel he was transferred to the Seventh Infantry April 10, 1817, and saw much service in the south in the Seminole War; colonel March 16, 1820, and brevet Brigadier-general March 16, 1830, for ten years faithful service in one grade; he died at Fort Smith June, 1851.[↩]

- Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), April 2, 1822, p. 3, col. 1. The Arkansas Gazette, the first number of which was published at Arkansas Post Nov. 20, 1 8 19, was removed to Little Rock where the first issue appeared Dec. 29, 1821.[↩]

- Arkansas Gazette, (Little Rock), April 9, 1822, p. 3, col. 1.[↩]

- In May the Robert Thompson made her second trip to Fort Smith towing a deeply laden keel boat and a sixty-five-foot half-loaded flat boat.[↩]

- Fort Towson was named for Nathan Towson, Paymaster General. Soon after it was established soldiers and officers became involved in differences with the white settlers near by to the extent of resisting the civil authority of the Territory of Arkansas which was claimed to extend to the adjoining part of what is now Texas. In the summer of 1829 the garrison was abandoned, the five yoke of oxen and two ox wagons were sold, and the troops and effects were removed on four flat-bottom boats down Red River to Cantonment Jesup near Natchitoches. Scarcely had they left when persons in the neighborhood fired and burned all the buildings of the garrison. About a year and a half later four companies of the Third Infantry under Major S. W. Kearny ascended Red River again to the mouth of the Kiamichi, and established another on the site of the old post, which on May 1, 1831, was designated Camp Phoenix; November 20, 1831, it was officially named Cantonment Towson, and February 8, 1832, Fort Towson.[↩]

- Indian Office, Retired Classified Files, folio drawer, manuscript copy of treaty.[↩]

- War Department, Adjutant-general’s office, General Orders No. 20, March 6, 1824. In the Senate discussion of the proposed change, in February 1824, it was considered that the new post would afford protection to traders between Missouri and Santa Fe. – American State Papers, “Indian Affairs”, vol. ii, 456.[↩]

- While this Arkansas line was moved east in 1828 (Kappler, op. cit., vol. ii, 206) to approximately where it now is, the western line established in 1824 was preserved and employed as the dividing line between the Cherokee and Creek Nations in their treaty of 1833 (Kappler, op. cit., vol. ii, 287), extending north and south a few miles east of where Wagoner, Oklahoma, now is.[↩]

- The correspondence involved in the controversy over Lovely’s Purchase was attached to a letter from the Secretary of War responsive to a resolution of the House of Representatives and published in U. S. House, Documents 20th congress, first session, no. 263.[↩]

- Lovely county embraced what are now Sequoyah, Adair, Ottawa, Delaware, and Cherokee, and parts of Muskogee, Wagoner, Mayes, and Craig counties, Oklahoma.[↩]

- Cephas Washburn to Jeremiah Evarts, September, 1830, Board for Foreign Missions, Boston, Manuscript Library, vol. 73, no. 2. For the Cherokee Treaty of 1828, see Kappler, op. cit., vol. ii, 206.[↩]

- Kappler, op. cit., vol. ii, 153. This treaty was made in Saint Louis June 2. On August 10 of that summer, another treaty ((Kappler, op. cit., vol. ii, 174[↩]

- Kappler, op. cit., vol. ii, 151.[↩]

- American State Papers, “Indian Affairs” vol. ii, 768.[↩]

- Kappler, op. cit., vol. ii, 188.[↩]

- David Brearly was born in New Jersey and became captain of the Light Dragoons May 3, 1808. With the Seventh Infantry he saw active service in the Seminole War; while colonel of that regiment he resigned from the Army, on March 16, 1820, and in the following June the President appointed him agent for the Western Cherokee in place of Reuben Lewis former agent, brother of Meriwether Lewis, who had resigned, and in September he began his duties in Arkansas. In 1833 he was appointed postmaster at Dardennelles, Arkansas, where he died in 1837.[↩]

- Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), February 13, 1828, p. 3, col. 1.[↩]

- Soon after the removal of the Mcintosh Creeks in 1829 a school was established in this settlement. “A school, which the [Baptist] convention commenced in 1823, on the Chattahoochee river, among the Creeks in Georgia, was transferred in 1830, upon the removal of the tribe, to a point about 20 miles above Fort Gibson on the Arkansas. The board has authorized the erection of buildings for the school and for the families attached to the mission. The station is under the care of the Rev. David Lewis, assisted by John Davis, an educated native, by whom the school has been regularly kept, but the number of pupils has not been reported.” – U.S. House. Executive Documents, 22d congress, second session, no. 2, Report of Secretary of War of November, 1832, p. 170. In 1832, Reverend Isaac McCoy arrived at this place where missionary labors had been conducted since October 1829 by John Davis [McCoy, Isaac. Annual Register of Indian Affairs, May 1837, No. iii, 19]. Here, [in a grove, near the Falls of Verdigris River] he said “On the 9th of September, I constituted the Muskogee Baptist Church, consisting of Mr. Lewis and wife, Mr. Davis and three black men, [named Quash, Bob, and Ned] who were slaves to the Creeks… This was the first Baptist church formed in the Indian Territory… The first act of the church after organizing, was to order a written license, as a preacher, to Mr. Davis, the Creek missionary, and I was directed to prepare the same.” – McCoy, Reverend Isaac, History of Baptist Indian Missions, 451. The next year other buildings were erected; a Sunday School was started and the establishment was called Ebenezer. It was three miles north of Arkansas River and four miles west of the Verdigris [Wyeth, Walter N. D.D. Isaac McCoy, Early Indian Missions, 193].[↩]