Cheyenne Indians (from the Sioux name Sha-hi’yena, Shai-ena, or (Teton) Shai-ela, ‘people of alien speech,’ from sha’ia, ‘to speak a strange language’). An important Plains tribe of the great Algonquian family. They call themselves Dzǐ’tsǐǐstäs, apparently nearly equivalent to ‘people alike,’ i.e. ‘our people’ from ǐtsǐstau. ‘alike’ or ‘like this’ (animate); (ehǐstă, ‘he is from, or of, the same kind’–Peter); by a slight change of accent it might also mean ‘gashed ones’, or possibly ‘tall people.’ The tribal form as here given is the third person plural.

The popular name has no connection with the French chien, ‘dog,’ as has sometimes erroneously been supposed. In the sign language they are indicated by a gesture which has often been interpreted to mean ‘cut arms’ or ‘cut fingers’ being made by drawing the right index finger several times rapidly across the left, but which appears really to indicate ‘striped arrows,’ by which name they are known to the Hidatsa, Shoshoni, Comanche, Caddo, and probably other tribes, in allusion to their old-time preference for turkey feathers for winging arrows.

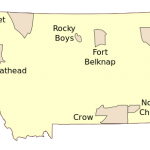

Cheyenne Locations

This tribe moved frequently; their territory comprised at some point in remembered or recorded history, land in the present states of Colorado, Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Wyoming.

The earliest authenticated habitat of the Cheyenne, before the year 1700, seems to have been that part of Minnesota bounded roughly by the Mississippi, Minnesota, and upper Red rivers. The Sioux, living at that period more immediately on the Mississippi, to the east and southeast, came in contact with the French as early as 1667, but the Cheyenne are first mentioned in 1680, under the name of Chaa, when a party of that tribe, described as living on the head of the great river, i. e., the Mississippi, visited La Salle’s fort on Illinois river to invite the French to come to their country, which they represented as abounding in beaver and other fur animals. The veteran Sioux missionary, Williamson, says that according to concurrent and reliable Sioux tradition the Cheyenne preceded the Sioux in the occupancy of the upper Mississippi region, and were found by them already established on the Minnesota.

At a later period they moved over to the Cheyenne branch of Red river, North Dakota, which thus acquired its name, being known to the Sioux as “the place where the Cheyenne plant,” showing that the latter were still an agricultural people (Williamson).

This westward movement was due to pressure from the Sioux, who were themselves retiring before the Chippewa, then already in possession of guns from the east. Driven out by the Sioux, the Cheyenne moved west toward Missouri river, where their further progress was opposed by the Sutaio – the Staitan of Lewis and Clark, a people speaking a closely cognate dialect who had preceded them to the west and were then apparently living between the river and the Black Hills.

After a period of hostility the two tribes made an alliance, some time after which the Cheyenne crossed the Missouri below the entrance of the Cannonball, and later took refuge in the Black Hills about the heads of Cheyenne river of South Dakota, where Lewis and Clark found them in 1804, since which time their drift was constantly west and south until confined to reservations.

Cheyenne Tribe History

Up to the time of Lewis and Clark they carried on desultory war with the Mandan and Hidatsa, who probably helped to drive them from Missouri river. They seem, however, to have kept on good terms with the Arikara. According to their own story, the Cheyenne, while living in Minnesota and on Missouri river, occupied fixed villages, practiced agriculture, and made pottery, but lost these arts on being driven out into the plains to become roving buffalo hunters.

On the Missouri, and perhaps also farther east, they occupied earth-covered log houses. Grinnell states that some Cheyenne had cultivated fields on Little Missouri river as late as 1850. This was probably a recent settlement, as they are not mentioned in that locality by Lewis and Clark. At least one man among them still understands the art of making beads and figurines from pounded glass, as formerly practiced by the Mandan.

There is some doubt as to when or where the Cheyenne first met the Arapaho, with whom they have long been confederated; neither do they appear to have any clear idea as to the date of the alliance between the two tribes, which continues unbroken to the present day. Their connection with the Arapaho is a simple alliance, without assimilation, while the Sutaio have been incorporated bodily. During the time of Long’s expedition to the Rocky Mountains, in 1819 and 1820, a small portion of the Cheyenne seem to have separated themselves from the rest of their nation on the Missouri, and to have associated themselves with the Arapaho who wandered about the tributaries of the Platte and Arkansas, while those who remained affiliated with the Ogalalla.

Their modern history may be said to begin with the expedition of Lewis and Clark in 1804. Constantly pressed farther into the plains by the hostile Sioux in their rear they established themselves next on the upper branches of the Platte, driving the Kiowa in their turn farther to the south.They made their first treaty with the Government in 1825 at the mouth of Teton (Bad) river, on the Missouri, about the present Pierre, South Dakota. In consequence of the building of Bent’s Fort on the upper Arkansas, in Colorado, in 1832, a large part of the tribe decided to move down and make permanent headquarters on the Arkansas, while the rest continued to rove about the headwaters of North Platte and Yellowstone rivers.

This separation was made permanent by the treaty of Ft Laramie in 1851, the two sections being now known respectively as Southern and Northern Cheyenne, but the distinction is purely geographic, although it has served to hasten the destruction of their former compact tribal organization. The Southern Cheyenne are known in the tribe as Sówoníă, ‘southerners,’ while the Northern Cheyenne are commonly designated as O’mǐ’sǐs eaters,’ from the division most numerously represented among them.

Their advent upon the Arkansas brought them into constant collision with the Kiowa, who, with the Comanche, claimed the territory to the southward. The old men of both tribes tell of numerous encounters during the next few years, chief among these being a battle on an upper branch of Red river in 1837, in which the Kiowa massacred all entire party of 48 Cheyenne warriors of the Bowstring society after a stout defense, and a notable battle in the following summer of 1838, in which the Cheyenne and Arapaho attacked the Kiowa and Comanche on Wolf creek, northwest Oklahoma, with considerable loss on both sides.

About 1840 the Cheyenne made peace with the Kiowa in the south, having already made peace with the Sioux in the north, since which time all these tribes, together with the Arapaho, Kiowa, Kiowa Apache, and Comanche have usually acted as allies in the wars with other tribes and with the whites.

For a long time the Cheyenne have mingled much with the western Sioux, from whom they have patterned in many details of dress and ceremony. They seem not to have suffered greatly from the small-pox of 1837-39, having been warned in time to escape to the mountains, but in common with other prairie tribes they suffered terribly from the cholera in 1849, several of their bands being nearly exterminated. Culbertson, writing a year later, states that they had lost about 200 lodges, estimated at 2,000 souls, or about two-thirds of their whole number before the epidemic.

Their peace with the Kiowa enabled them to extend their incursions farther to the south, and in 1853 they made their first raid into Mexico, but with disastrous result, losing all but 3 men in a fight with Mexican lancers. From 1860 to 1878 they were prominent in border warfare, acting with the Sioux in the north and with the Kiowa and Comanche in the south, and have probably lost more in conflict with the whites than any other tribe of the plains, in proportion to their number.

In 1864 the southern band suffered a severe blow by the notorious Chivington massacre (Sand Creek Massacre) in Colorado, and again in 1868 at the hands of Custer in the battle of the Washita. They took a leading part in the general outbreak of the southern tribes in 1874-75.

The Northern Cheyenne joined with the Sioux in the Sitting Bull war in 1876 and were active participants in the Custer massacre. Later in the year they received such a severe blow from Mackenzie as to compel their surrender. In the winter of 1878-79 a band of Northern Cheyenne under Dull Knife, Wild Hog, and Little Wolf, who had been brought down as prisoners to Fort Reno to be colonized with the southern portion of the tribe in the present Oklahoma, made a desperate attempt at escape. Of an estimated 89 men and 146 women and children who broke away on the night of Sept. 9, about 75, including Dull Knife and most of the warriors, were killed in the pursuit which continued to the Dakota border, in the course of which about 50 whites lost their lives. Thirty-two of the Cheyenne slain were killed in a second break for liberty from Fort Robinson, Nebraska, where the captured fugitives had been confined. Little Wolf, with about 60 followers, got through in safety to the north. At a later period (1882) the Northern Cheyenne were assigned to the present reservation in Montana.

The Southern Cheyenne were assigned to a reservation in western Oklahoma by treaty of 1867, but refused to remain upon it until after the surrender of 1875, when a number of the most prominent hostiles were deported to Florida for a term of 3 years. In 1901-02 the lands of the Southern Cheyenne were allotted in severalty and the Indians are now American citizens.

Cheyenne Treaties

The following treaties were instrumental in establishing and defining the relationship between the United States and the Arapaho and Cheyenne Confederation. They also impacted the history of the tribe after it signed the initial treaty of 1825. Each succeeding treaty will show the historian a shrinking land mass controlled by the Arapaho and Cheyenne. Before reading the actual treaties I suggest that you read our overview of each one and their impact on the tribe:

Outside of listing the signers of each treaty, the treaty of 1865 included a list of individuals who were related to the Arapaho and Cheyenne Tribes and whom the confederation wished to be allotted land from the reservation of the original treaty signed in 1851. This list likely includes many half-breeds and would be considered proof of prior tribal affiliation for descendants of any of the people listed.

- Treaty of July 6, 1825

- Treaty of September 17, 1851

- Treaty of February 15, 1861

- Treaty of October 14, 1865

- Treaty of October 17, 1865

- Treaty of October 28, 1867

- Treaty of May 10, 1868

After the treaty of 1868, the Northern Arapaho and Cheyenne became embroiled in the continuous Sioux hostilities with the United States, taking an active part in the defeat of Custer at Little Bighorn in 1876. They likely also resented that they had no land for themselves. Between 1881-1883 Little Chief and some of this band of Northern Cheyenne moved from the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency, Indian Territory to the Pine Ridge Agency, Dakota Territory. Finally, in 1884, the Northern Cheyenne received their own reservation, set aside for them, by executive order, in the state of Montana, called the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

Cheyenne Nation

Northern Cheyenne. The popular designation for that part of the Cheyenne which continued to range along the upper Platte after the rest of the tribe (Southern Cheyenne) had permanently moved down to Arkansas river, about 1835. They are now settled on a reservation in Montana. From the fact that the Omisis division is most numerous among them, the term is frequently used by the Southern Cheyenne as synonymous.

Consult Further:

Cheyenne Sioux. Possibly a loose expression for Cheyenne River Sioux i.e., the Sioux on Cheyenne Rivers reservation, South Dakota; but more probably, considering the date intended to designate those Sioux chiefly of the Oglala division who were accustomed to associate and intermarry with the Cheyenne. The term occurs in Ind. Aff. Rept., 41, 1856

Southern Cheyenne. That part of the Cheyenne which ranged in the south portion of the tribal territory after 1835, now permanently settled in Oklahoma. They are commonly known as Sówoniǎ ‘southerners (from Sowón, ‘south”), by the Northern Cheyenne, and sometimes as Hevhaitanio, from there most numerous divisions.

Cheyenne Subdivisions

Following are the bands which had a well-recognized place in the camp circle, as given by Mooney (1928):

- Hevǐgs’-nǐ”pahǐs

- Mŏǐséyu

- Wŭ’tapíu

- Hévhaitä’nio

- Oǐ’vimána

- Hǐsíometä’nio

- Sŭtáio (formerly a distinct tribe; see below)

- Oqtógŭnă

- Hó’nowă

- Măsǐ”kotă

- O’mǐ’sǐs

Other band names not commonly recognized as divisional names, are these:

- Mogtávhaitä’niu

- Ná’kuimána

- Anskówǐnǐs

- Pǐ’nûtgû’

- Máhoyum

- Wóopotsǐ’t

- Totoimana (on Tongue River)

- Black Lodges (near Lame Deer)

- Ree Band

- Yellow Wolf Band

- Half-breed Band

Consult Further:

Cheyenne Tribe Culture and Life

Under their old system, before the division of the tribe, the Cheyenne had a council of 44 elective chiefs, of whom 4 constituted a higher body, with power to elect one of their own number as head chief of the tribe. In all councils that concerned the relations of the Cheyenne with other tribes, one member of the council was appointed to argue as the proxy or “devil’s advocate” for the alien people. This council of 44 is still symbolized by a bundle of 44 invitation sticks, kept with the sacred medicine-arrows, and formerly sent around when occasion arose to convene the assembly.

Consult Further:

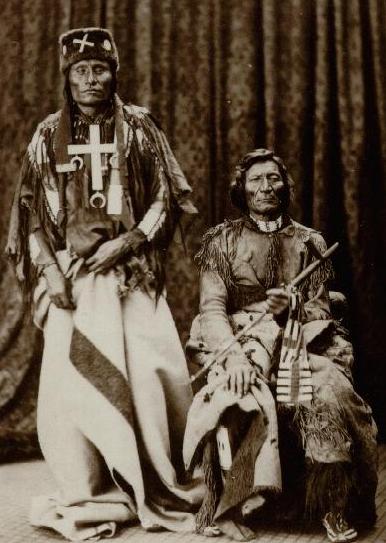

Cheyenne Indians Chiefs and Leaders

- Cheyenne Indian Chiefs and Leaders

- Black Kettle

- Dull Knife

- Hishkowits

- Roman Nose

- Standing Elk

- Chief Two Moon

- White Shield Owner

- Wolf Robe

- Wopohwats

Cheyenne Tribe Religion

In a sacred tradition recited only by the priestly keeper, they still tell how they “lost the corn” after leaving the eastern country. One of the starting points in this tradition is a great fall, apparently St Anthony’s falls on the Mississippi, and a stream known as the “river of turtles,” which may be the Turtle river tributary of Red river, or possibly the St Croix, entering the Mississippi below the mouth of the Minnesota, and anciently known by a similar name.

Although the alliance between the Sutaio and the Cheyenne dates from the crossing of the Missouri river by the latter, the actual incorporation of the Sutaio into the Cheyenne camp-circle probably occurred within the last hundred years, as the two tribes were regarded as distinct by Lewis and Clark. There is no good reason for supposing the Sutaio to have been a detached hand of Siksika drifted down directly from the north, as has been suggested, as the Cheyenne expressly state that the Sutaio spoke “a Cheyenne language,” i. e. a dialect fairly intelligible to the Cheyenne, and that they lived southwest of the original Cheyenne country.

The linguistic researches of Rev. Rudolph Petter, our best authority on the Cheyenne language, confirm the statement that the difference was only dialectic, which probably helps to account for the complete assimilation of the two tribes.

The Cheyenne say also that they obtained the Sun dance and the Buffalo-head medicine from the Sutaio, but claim the Medicine-arrow ceremony as their own from the beginning. Up to 1835, and probably until reduced by the cholera of 1849, the Sutaio retained their distinctive dialect, dress, and ceremonies, and camped apart from the Cheyenne. In 1851 they were still to some extent a distinct people, but exist now only as one of the component divisions of the (Southern) Cheyenne tribe, in no respect different from the others. Under the name Staitan (a contraction of Sŭtai-hitän, pl. Sŭtai-hitänio, ‘Sŭtai men’) they are mentioned by Lewis and Clark in 1804 as a small and savage tribe roving west of the Black Hills.

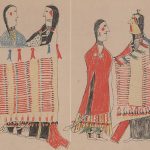

Those in the north seem to hold their own in population, while those of the south are steadily decreasing. They numbered in 1904-Southern Cheyenne, 1,903; Northern Cheyenne, 1,409, a total of 3,312. Although originally an agricultural people of the timber country, the Cheyenne for generations have been a typical prairie tribe, living in skin tipis, following the buffalo over great areas, traveling and fighting on horseback. They commonly buried their dead in trees or on scaffolds, but occasionally in caves or in the ground. In character they are proud, contentious, and brave to desperation, with an exceptionally high standard for woman. Polygamy was permitted, as usual with the prairie tribes.

Housing of the Cheyenne Tribe

While living in the vicinity of the Minnesota the villages and camps of the Cheyenne undoubtedly resembled those of the Sioux of later days; the conical skin-covered lodge, or possibly the mat or bark structure of the timber people, as used by the Ojibway and others. But during the same period it is evident other bands of the tribe lived quite a distance westward, probably on the banks of the Missouri, and there the habitations were the permanent earth lodge, similar to those of the Pawnee, Mandan, and other Missouri Valley tribes. Unfortunately no sketch or picture of any sort of a Cheyenne earth lodge is known to exist, but the villages must have resembled in appearance those of the Pawnee of a later generation, remarkable photographs of which have been preserved

Cheyenne Genealogical Research

Researchers who believe they are descended from the Cheyenne will be limited in their research to the amount of records available which provide specific names, and even further, those records which provide proof of relationships. The first source should be the Free US Indian Census Schedules 1885-1940 as provided below which cover the years of 1885-1940. Determining an ancestor in those records would verify descendancy, especially in those census after 1930 when the degree of Indian Blood is provided. Further research can also be conducted using the following tools:

Cheyenne Indians Rolls and Census

- Cantonment Agency

- Cheyenne and Arapahoe Reservation

- 1887-1888 Cheyenne and Arapahoe Reservation Census

- 1891-1894 Cheyenne and Arapahoe Reservation Census

- 1895-1904 Cheyenne and Arapahoe Reservation Census

- 1905-1920 Cheyenne and Arapahoe Reservation Census

- 1921-1930 Cheyenne and Arapahoe Reservation Census

- 1931-1933 Cheyenne and Arapahoe Reservation Census

- 1934-1939 Cheyenne and Arapahoe Reservation Census

- Pine Ridge Agency

- 1886 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1887-1888 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1890 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1891 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1892 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1893 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1894-1895 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1896-1899 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1900-1903 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1904-1905 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1907 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- 1909 Pine Ridge Agency Census

- Red Moon Agency

- Seger Agency

- Tongue Agency River

The Cheyenne Today

For Further Study on the Cheyenne Tribe

The following articles and manuscripts will shed additional light on the Cheyenne as both an ethnological study, and as a people.

- Carver, Travels, 1796; Clark, Indian Sign Language, 1885.

- Culbertson in Smithson. Rep. for 1850-1851.

- Dorsey, The Cheyenne, Field Columb. Mus. Publ., Anthrop. ser., ix, nos. 1 and 2, 1905.

- Grinnell, various letters and published papers, notably Social Org. of the Cheyenne, in Proc. Internat. Cong. Americanists for 1902, 1905.

- Hayden, Ethnog. and Philol. Mo. Val., 1862.

- History of Arapaho and Cheyenne Treaties.

- Howbert, Irving. The Indians of the Pike’s Peak Region. New York: Knickerbock Press. 1914.

- Jackson, Helen Hunt. A century of dishonor: a sketch of the United States government’s dealings with some of the Indian tribes. Little, Brown. 1885.

- La Salle in Margry, Découvertes, II, 1877;

- Lewis and Clark, Travels, I, ed. 1842;

- Margry, couvertes, 11, 1877

- Margry, Maximilian, Travels, 1843

- Mooney, Ghost Dance Religion, 14th Rep. B. A. E., 1896

- Mooney, Calendar Hist. of the Kiowa, 17th Rep. B. A. E., 1898

- Mooney, Cheyenne MS., B. A. E.

- Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs

- War Dept. Record of Engagements with Hostile Indians, 1882

- Williamson in Minn. Hist. Soc. Coll., I, 1872.