The following account of the annual ceremony of the Sand Creek Yuchi is based upon notes made at the time, and upon incidental information derived from participants. It deals chiefly with the 1905 celebration although there was no appreciable difference between that of 1904 and the event of 1905.

The Preliminary Day. – According to the evidences of maturity observable in the corn in the neighboring fields, and the approaching phase of the moon, the town chief or head priest (Jim Brown) appointed and announced, to the townspeople scattered through out the neighboring district, a day of general assembly, at which small bundles of sticks about two inches in length (Fig. 37) were distributed to the heads of families. The number of sticks in the bundles indicated the number of days that should pass before the ceremonies would take place. The day had already been decided upon by the chief and was announced at this preliminary meeting. A stick was thrown away each morning thereafter until but one remained, and that was the day of the next assembly at the public square. Dancing took place at this meeting to give a little practice to the men, as they said. Arrangements were also made for the repair of the lodges, and the obtaining of the beef for the barbecue which was to close the event. In other words, this meeting was purely preparatory. All the top earth was carefully taken from the square and placed in a heap behind the north lodge.

When the day arrived for the formal celebration to commence, the Yuchi took care to be on hand before nightfall at the public square, which was situated in a permanent locality near Scull Creek, where a beautiful spring of clear water flowed from a side hill. The ceremony this time was to last three days and to include the following ritualistic events. The first day was to be a general gathering, with the commencement of the fast and dancing all through the first half of that night. On the second day, the new fire ceremony was to take place after sunrise, followed by the preparation of the medicines, the scarification, the taking of the emetic, the breaking the fast, and the ceremonial ball game. The ensuing night was to be given up to all-night dancing. On the third day, the people were to disband for a while and return again, after a rest, for several subsequent days of minor observances. This was the plan given out for the carrying on of the celebration.

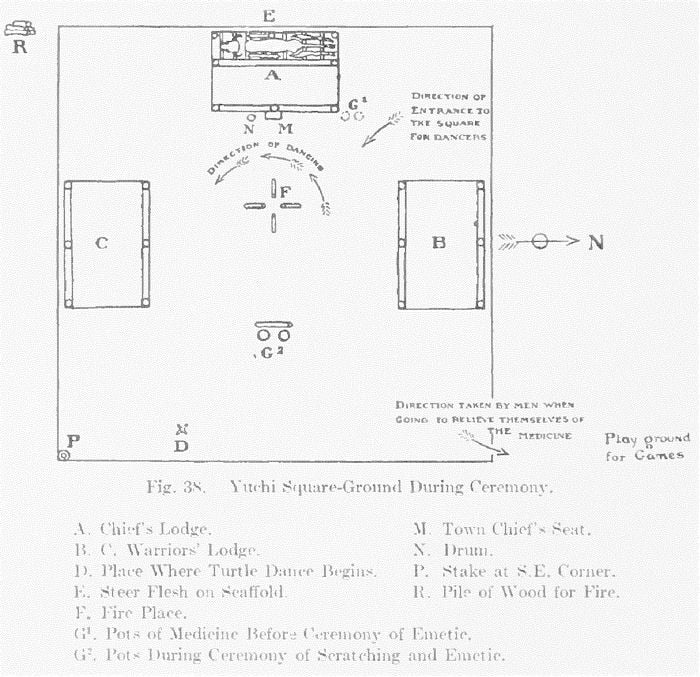

An explanatory diagram of the square-ground showing some of the things mentioned in the following description is given (Fig. 38) and will be frequently referred to in the account. The date of the 1904 ceremony was July 17; that of 1905 was a few days later in the same month.

First Day. – About one hundred Yuchi having arrived, upon the day set aside in the preliminary gathering, at the camping ground surrounding the public square, friendly intercourse was held among the to townsfolk, and sumptuous preparations were made for the evening meal, after which no food could be eaten by adults until the ceremony of taking the emetic was over.

Before dark the four yätcigi’ went out in single file toward the woods east to secure the four logs for the new fire, to be started the next morning, and also to dig the two medicine roots ƒeâde’ and to tcalá and to secrete them where they could be readily found when they were to be brought in. Before appearing at the camp on their return, they whooped four times to apprise the town of the commencement of the ceremony and the fast. This whooping caused quite a little commotion among the people. Their manner changed and it seemed as though they were under constraint. The spirits of the summer ceremonial were then supposed to be watching them for infringements of the taboos. Salt and the other things spoken of before were tabooed from this time until the end of the celebration. The four logs were then deposited in the west lodge, where the Chiefs and their paraphernalia reposed.

At about ten o’clock in the evening, the moon being at the first quarter and over the West lodge, the town chief’s assistant, who will here-after be called second chief , and the goconé or master of ceremonies from the Warrior Society, called in a loud voice to the town to come to dance. Mean while the goconé had started a fire of fagots in the center of the square, where the fire is always made (see diagram. Fig. 38). When the lodges were filled with the townsmen, the Däioeä’ or Big Turtle Dance was begun.

The Big Turtle Dance

In loose order, the leader having a hand rattle in his right hand, the dancers grouped themselves in the southeast corner of the square. (See diagram.) All formed in a compact mass and the leader in the center began moving in a circle, rattling and shouting ‘hó! hó!’ The dancers kept in close ranks behind him echoing his shouts. After about five minutes of this, the leader started toward the fire and the dancers all held hands. A woman having the turtle shell rattles on her legs came from the northwest comer and took her place behind the leader holding hands with him. In single file the latter led them around the fire, sunwise. In 1905 there were two of these women. When the men whooped they were joined by two more, when they whooped again the women left the line. After circling a number of times the leader stopped, stamped and whooped and the ranks broke up, the dancers dispersing to their various lodges about the square. The first song was thus finished. After a short interval a leader stepped toward the fire and circling it alone started the second song and was soon joined by other dancers. Two or more women having the shell rattles on their legs took part. During the course of the next few songs the leader took the line to each of the four comers of the square, led them around in a circle and then back to the fire. No drumming accompanied this dance. Women joined in as well as children and strangers. This dance was continued for about two hours, at intervals, and was the only one danced on this night. (See Plate XII.) 1

During the process of this dance, and in all the others too, the goconé exhorted the dancers to their best by shouting out encouragement, and with his long staff went about to secure song leaders during the intervals of rest. The Thunder was frequently invoked this night by the goconé with cries of PictanAn’! PictanAn’! “Thunder! Thunder!”

At about midnight when things had quieted down a little, the town chief rose from his seat near the center of the west lodge, and silence was rendered him as he began a speech lasting about fifteen minutes. In this he referred to their ancestors who handed the ceremonies down to them; to the deities who taught them; to the obligations of the present generation to maintain them. He complimented the dancers, referred to the rites of the next day and called for the assent and cooperation of his town. The men then shouted ‘hó! hó!’ the sign of approbation. The town chief concluded with an appeal for good behavior and reverence during the celebration, exhorting them when the event was over to go to their homes in peace and to avoid getting into trouble or disputes with anyone. Then all dispersed for the purpose of sleep or carousing.

Second Day. – Before sunrise of the second day the town chief took his seat in the West lodge. Now the four yatcigi passed off toward the east to bring in the medicine plants. During their absence the town chief was preparing the flints and steel for the new fire. The return of the yatcigi was announced by a series of whoops {‘háyo! háyo!’) and they came in with the plants, depositing them in the west lodge.

Citations:

- When the first flashlight (Pl. XII, 2) was discharged in making these exposures some of the dancers stopped and some went right on, but they seemed greatly startled and for a moment blinded. Several chiefs then came over and expressed their displeasure. They called it “lightning. ” I explained that no harm was meant and finally got their consent to make another (Pl. XII, 1) somewhat nearer.[↩]