It may be asked why we did not receive protection from the territorial authorities. The reason for this was that the Territory was without funds or a military organization. The Governor had repeatedly called the attention of the General Government to the helpless condition of our settlements, and asked that government troops be sent to protect them from the raids of the Indians; but at this time the entire military force of the nation was employed in suppressing the Rebellion, and little aid could be given. It is true that the companies of the First Regiment of Colorado Cavalry were distributed along the frontier, seldom more than one company in a place. Scattered in this way over a wide extent of country, they were of little or no use in the way of defense.

Meanwhile, the Indians were in virtual possession of the lines of travel to the east. Every coach that came through from the Missouri River to Denver had to run the gauntlet. Some were riddled with bullets, others were captured and their passengers killed. Instances were known where the victims were roasted alive, shot full of arrows, and subjected to every kind of cruelty the savages could devise. Finally, after many urgent appeals, the Governor of Colorado was permitted to organize a new regiment to be used in protecting the frontier settlements and in punishing the hostile Cheyenne and Arapaho. The term of service was to be one hundred days; it was thought that by prompt action signal punishment could be inflicted on the savages in that time. Lieut. George L. Shoup, of the First Colorado, was commissioned as Colonel of the new regiment, which was designated as the Third Regiment of Colorado Volunteer Cavalry. Colonel Shoup had already proved himself to be a very able and efficient officer. He was afterward for many years United States Senator from the State of Idaho. From the day he received his appointment, he proceeded with great activity to organize his command. Recruiting officers had already been placed in almost every town in the Territory, and in less than thirty days eight or nine hundred men had been enlisted. Eight or ten others from El Paso County besides myself joined the regiment at the first call. Among them were Anthony Bott, Robert Finley, Henry Coby, Samuel Murray, John Wolf, A. J. Templeton, Henry Miller, and a number of others whose names I do not now remember. The recruits from El Paso County were combined with those from Pueblo County and mustered in as Company G at Denver on the 29th day of August 1864. Our officers were 0. H. P. Baxter of Pueblo, Captain; Joseph Graham of the same county, First Lieutenant; and A. J. Templeton of El Paso County, Second Lieutenant. Within a short time after we had been mustered in at Denver, we marched back through El Paso County and south to a point on the Arkansas River, five miles east of Pueblo, where we remained for the next two months, waiting for our equipment. Meanwhile, we were being drilled and prepared for active military duty.

On the last day of October and the first day of November of that year there was a tremendous snowstorm all over the region along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains. The snowfall at our camp was twenty inches in depth; at Colorado City it was over two feet on the level, and on the Divide still deeper. All supplies for the company had to be brought to our camp by teams, from the Commissary Department at Denver. The depth of the snow now made this impossible; consequently, in a few days we were entirely out of food. As there seemed to be no hope of relief within the near future, our Captain instructed every one who had a home to go there and remain until further notice. Half a dozen of us from El Paso County started out the following morning before daylight, and tramped laboriously all day and well into the night through deep snow along the valley of the Fountain. For a portion of the way a wagon or two had gone over the road since the storm, making it so rough that walking along it was almost impossible. As a result, we were so tired by dusk that we would have traveled no farther could we have found a place where food and shelter were to be obtained; but it was eleven o’clock that night before we could get any accommodations at all, and by that time we were utterly exhausted. We resumed our tramp the next morning, but I was two days in reaching my home in Colorado City, twenty-five miles distant. Two weeks later we were notified by our Captain that provisions had been obtained and that we should return to camp at once. We had already been clothed in the light blue uniform then used by the cavalry branch of the United States Army. Soon after our return to camp we received our equipment of arms, ammunition, and the necessary accouterments. The guns were old, out-of-date Austrian muskets of large bore with paper cartridges from which we had to bite off the end when loading. These guns sent a bullet rather viciously, but one could never tell where it would hit. A little later on, our horses arrived. They were a motley looking group, composed of every kind of an equine animal from a pony to a plow horse. The saddles and bridles were the same as were used in the cavalry service and were good of the kind. I had the misfortune to draw a rawboned; square built old plow horse, upon which thereafter I spent a good many uncomfortable hours. If the order came to trot, followed by an order to gallop, I had to get him well underway on a trot and he would be going like the wind before I could bring him into the gallop. Meanwhile his rough trot would be shaking me to pieces. From what I have said, it will be seen that our equipment, as to arms and mounts, was of the poorest kind.

The main part of the regiment had been in camp near Denver during all this time. This inactivity had caused a great deal of complaint among the officers and enlisted men. For the most part, the regiment had been enlisted from the ranchmen, miners, and business men of the State, and it was the understanding that they were to be given immediate service against the hostile Indians. The delay was probably unavoidable, being caused by the inability of the Government to promptly furnish the necessary horses and equipment, as the animals had to be sent from east of the Missouri River. The horses and equipment were received about the middle of November. A few days later, under command of Colonel Shoup, the main part of the regiment, together with three companies of the First Colorado, started on its way south, towards a destination known only to the principal officers. The combined force was under command of Col. John M. Chivington, commander of the military district of Colorado. The company to which I belonged joined the regiment as it passed our camp, about the 25th of November, and from that time on our real hardships began. We marched steadily down the valley of the Arkansas River, going into camp at seven or eight o’clock every night, and by the time we had eaten supper and had taken care of our horses, it was after ten o’clock. We were called out at four o’clock the next morning and were on the move before daylight. In order that no news of our march should be carried to the Indians, every man we met on the road was taken in charge, and, for the same purpose, guards were placed at every ranch.

About four o’clock in the evening of November 28th, we arrived at Fort Lyon, to the great surprise of its garrison. No one at the fort even knew that the regiment had left the vicinity of Denver. A picket guard was thrown around the fort to turn away any Indians that might be corning in, and also to prevent any of the trappers or Indian traders who generally hung around there from notifying the savages of our presence.

Soon after our arrival at camp, we were told that the wagon train would be left behind at this point, and each man was instructed to secure from the commissary two or three pounds of raw bacon and sufficient ” hardtack ” to last three or four days, which he was to carry in his saddlebags. At eight o’clock that night, the regiment took up its line of march across the prairie, in a direction almost due north from Fort Lyon. Each company was formed into fours, and we pushed on rapidly. All night long it was walk, trot, gallop, dismount and lead. I had had very little sleep for two or three nights previously, and, consequently, this all-night march was very exhausting. During the latter part of the night, I would willingly have run the risk of being scalped by the Indians for a half-hour’s sleep. Some time after midnight, our guide, intentionally as we thought, led us through one of the shallow lakes that are so plentiful on the plains of that region. He was understood to be more friendly to the Indians than to the whites, and perhaps he hoped our ammunition would get wet, and thus become ineffective in the anticipated engagement. During the night, in order to keep awake, we had been nibbling on our hardtack, which in the morning, much to our disgust, we found to be very much alive.

It was a bright, clear, starlight night; the air was crisp and uncomfortably cool, as might be expected at that time of year. Just as the sun was coming up over the eastern hills, we reached the top of a ridge, and away off in the valley to the northwest we saw a great number of Indian tents, forming a village of unusual size. We knew at once that this village was our objective point. Off to the left, between us and the village, was a large number of Indian ponies.

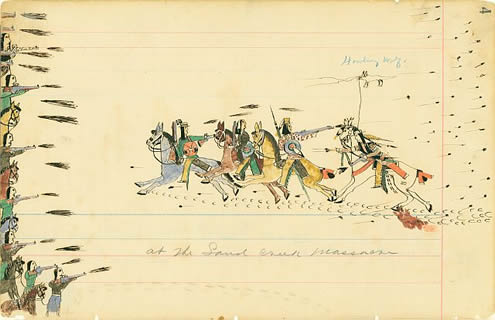

Two or three minutes later, orders came directing our battalion to capture the herd. Under command of a Major of the regiment, we immediately started on the run in order to get between the ponies and the Indian camp before our presence was discovered. We had not proceeded any great distance before we saw half a dozen Indians coming toward the herd from the direction of the camp, but, on seeing our large force, they hesitated a moment and then started back as fast as their ponies could take them. We were not long in securing the herd, which consisted of between five and six hundred ponies. The officer in command placed from twenty to thirty men in charge of the ponies, with instructions to drive them away to some point where they would be in no danger of recapture. The remainder of the battalion then started directly for the Indian camp, which lay over a little ridge to the north of us. Meanwhile, the main part of the command had marched at a rapid rate down the slope to Sand Creek, along the northern bank of which the Indian camp was located. Crossing the creek some distance to the eastward of the village, they marched rapidly westward along the north bank until near the Indian village, where they halted, and the battle began. At the same time our battalion was coming in from the south. This left an opening for the Indians to the westward, up the valley of Sand Creek, and also to the northward, across the hills towards the Smoky Hill River. Before our battalion had crossed the low ridge which cut off the view of the village at the point where we captured the ponies, and had come in sight of the village again, the firing had become general, and it made some of us, myself among the number, feel pretty queer. I am sure, speaking for myself, if I hadn’t been too proud, I should have stayed out of the fight altogether.

When we first came in sight of the Indian camp there were a good many ponies not far away to the north of it, and now when we came in sight of the camp again, after we had captured the other herd, we saw large numbers of Indians, presumably squaws and children, hurrying northward on these ponies, out of the way of danger. After the engagement commenced, the Indian warriors concentrated along Sand Creek, using the high banks on either side as a means of defense. At this point, Sand Creek was about two hundred yards wide, the banks on each side being almost perpendicular and from six to twelve feet high. The engagement extended along this creek for three or four miles from the Indian encampment. Our capture of the ponies placed the Indians at a great disadvantage, for the reason that an Indian is not accustomed to fighting on foot. They were very nearly equal to us in numbers, and had they been mounted, we should have had great difficulty in defeating them, as they were better armed than we were, and their ponies were much superior for military purposes to the horses of our command.

From the beginning of the engagement our battery did effective work, its shells, as a rule, keeping the Indians from concentrating in considerable numbers at any one point. However, at one place, soon after getting into the fight, I saw a line of fifty to one hundred Indians receive a charge from one of our companies as steadily as veterans, and their shooting was so effective that our men were forced to fall back. Returning to the charge soon after, the troopers forced the Indians to retire behind the banks of the creek, which they did, however, in a very leisurely manner, leaving a large number of their dead upon the field. Our own company, Company G, became disorganized early in the fight, as did many of the other companies, and after that fought in little groups wherever it seemed that they could be most effective. After the first few shots, I had no fear whatever, nor did I see any others displaying the least concern as to their own safety. The fight soon became general all up and down the valley, the Indians continuously firing from their places of defense along the banks, and a constant fusillade being kept up by the soldiers, who were shooting at every Indian that appeared. I think it was in this way that a good many of the squaws were killed. It was utterly impossible, at a distance of two hundred yards, to discern between the sexes, on account of their similarity of dress.

As our detachment moved up the valley, we frequently came in line of the firing, and the bullets whizzed past us rather unpleasantly, but fortunately none of us was hurt. At one point we ran across a wounded man, a former resident of El Paso County, but then a member of a company from another county. A short time previously, as he passed too near the bank, a squaw had shot an arrow into his shoulder, inflicting a very painful wound. He was being cared for by the members of his own company. A little farther up the creek we crossed over to the north side, and then moved leisurely up the valley, shooting at the Indians whenever any were in sight. By this time, most of them had burrowed into the soft sand of the banks, which formed a place of defense for them from which they could shoot at the whites, while only slightly exposing themselves.

Soon after, we joined a detachment which was carrying on a brisk engagement with a considerable force of Indians, some of whom were hidden behind one of the many large piles of driftwood along the banks of Sand Creek, while others were sheltered behind a similar pile in the center of the creek, which was unusually wide at that point. Our men were posted in a little depression just back from the north bank, from which some of them had crawled forward as far as they dared go, and were shooting into the driftwood, in the hope of driving the Indians from cover. Soon after I reached this point, a member of the company from Boulder, who had stepped out a little too far, and then turned around to speak to one of us, was shot in the back, the bullet going straight through his lungs and chest. Realizing at once that he was badly wounded, probably fatally so, he asked to be taken to his company. I volunteered to accompany him and, after helping him on his horse, we started across the prairie to where his company was supposed to be. With every breath, bubbles of blood were coming from his lungs and I had little hope that he would reach his comrades alive. Just as we reached the company, he fainted and was caught by his captain as he was falling from his horse. I returned immediately to the place that I had left and found the battle still going on.

During my absence, our little force had been considerably increased by soldiers from other parts of the battlefield. It was now decided to make it so hot for the savages by continuous firing, that they would be compelled to leave their places of cover. Soon two or three of the Indians exposed themselves and were instantly shot down. In a short time, the remainder started across the creek towards its southern bank. They ran in a zigzag manner, jumping from one side to the other, evidently hoping by so doing that we would be unable to hit them, but by taking deliberate aim, we dropped every one before they reached the other bank.

About this time, orders came from the commanding officer directing us to return at once to the Indian camp, as information had been received that a large force of Indians was coming from the Smoky Hill River to attack us. Obeying this order, we marched leisurely down the creek, and as we went we were repeatedly fired at by Indians hidden in the banks in the manner I have described heretofore. We returned the fire, but the savages were so well protected that we had no reason to think any of our shots had proved effective. At one place, an Indian child, three or four years of age, ran out to us, holding up its hands and crying piteously. From its actions we inferred that it wished to be taken up. At first I was inclined to do so, but changed my mind when it occurred to me that I should have no means of taking care of the little fellow. We knew that there were Indians concealed within a couple of hundred yards of where we were, who certainly would take care of him as soon as we were out of the way; consequently we left him to be cared for by his own people. Every one of our party expressed sympathy for the little fellow, and no one dreamed of harming him.

As we neared the Indian camp, we passed the place where the severest fighting had occurred earlier in the day, and here we saw many dead Indians, a few of whom were squaws. At the edge of the camp, we came upon our own dead who had been brought in and placed in a row. There were ten of them, and we were informed that there were forty wounded in a hospital improvised for the occasion. Among the dead I expected to find the Boulder man whom I had taken to his company, but, strange to relate, he survived his wound, and I saw him two or three years afterwards, apparently entirely recovered. The number of our dead and wounded showed that the Indians had offered a vigorous defense, and as I have before stated, if they had been mounted, it is questionable whether the result would have been the same-had they remained to fight.

We reached the Indian camp about four o’clock in the afternoon, the battle having continued without cessation from early morning until that time. The companies were immediately placed in position to form a hollow square, inside of which our horses were picketed. I was so utterly exhausted for want of sleep and food, as were many others of our company, that I hunted up a buffalo robe, of which there were large numbers scattered around, threw myself down on it, and was asleep almost as soon as I touched the ground. The next thing I remember was being awakened for supper, about dusk. We were told that we must sleep with our guns in our hands, ready for use at any moment. Near midnight, we were awakened by a more than vigorous call of our officers, ordering us to fall into line immediately to repel an attack. We rushed out, but in our sleepy condition had difficulty in forming a line, as we hardly knew what we were doing. In the evening, by order of the commanding officer, all the Indian tents outside of our encampment had been set on fire and now were blazing brightly all around us.

We heard occasional shots in various directions, and in the light of the fire saw what looked to be hundreds of Indian ponies running hither and thither. We saw no Indians, but we knew that savages in an encounter always lie on the side of their ponies opposite from the enemies they are attacking From the number of what seemed to be horses that could be seen in every direction, we thought that we should surely be overwhelmed. After forming in line, and while waiting for the attack, we discovered that what in our sleepy condition we had imagined to be ponies, was nothing but the numerous dogs of the Indian camp, which, having lost their masters, were running wildly in every direction. Nevertheless, it was evident that Indians were all around us, as our pickets had been fired upon and driven in from every side of the camp. After remaining in line for a considerable length of time, without being attacked, the regiment was divided into two divisions, one of which was marched fifty feet in front of the other. We were then instructed to get our blankets, and, wrapping ourselves in them, with our guns handy, we lay down and slept the remainder of the night.

In the Indian camp we found an abundance of flour, sugar, bacon, coffee, and other articles of food, sufficient for our maintenance, had we needed it, for a time. In many of the tents there were articles of wearing apparel and other things that had been taken from wagon trains, which the Indians had robbed during the previous summer. In these same tents we found a dozen or more scalps of white people, some of them being from the heads of women and children, as was evidenced by the color and fineness of the hair, which could not be mistaken for that of any other race. One of the scalps showed plainly from its condition that it had been taken only recently. Certain members of our regiment found horses and mules in the Indian herd that had been stolen from them by the hostiles in their various raids during the preceding year. The camp was overflowing with proof that these Indians were among those who had been raiding the settlements of Colorado during the previous summer, killing people, robbing wagon-trains, burning houses, running off stock, and committing outrages of which only a savage could be guilty; this evidence only corroborated in the strongest possible manner what we already knew. Among the members of our regiment, there were many who had had friends and relatives killed, scalped, and mutilated by these Indians, and almost every man had sustained financial loss by reason of their raids; consequently it is not surprising they should be determined to inflict such punishment upon the savages as would deter them from further raids upon our settlements. Notwithstanding the fact that this grim determination was firmly fixed in the mind of every one, I never saw any one deliberately shoot at a squaw, nor do I believe that any children were intentionally killed.

About noon of the day following the battle, our wagon train came up, and was formed into a hollow square in the center of our camp, the lines being drawn in, so that if necessary the wagons could be used as a means of defense. We knew that on the Smoky Hill River, from fifty to seventy-five miles distant, there was another large body of Cheyenne and Arapaho which might attack us at any time In every direction throughout the day, many Indians were seen hovering around our camp. Scouting parties were seldom able to get very far away from camp without being fired upon, and several of our men were killed and a number wounded in the skirmishes that took place. During the second night of our stay on the battleground, we were kept in line continuously, with our arms ready for use at a moment’s notice. At intervals during the entire night, there was an exchange of shots at various points around the camp.

I never understood why we did not follow up our victory by an attack upon the hostile bands camped on the Smoky Hill River, but I assume it was on account of our regiment’s inferior horses, arms, and equipment. Probably Colonel Chivington, taking this into consideration, thought his force not strong enough to fight such a large party successfully.

The following day, the command took up its line of march down the Big Sandy and followed it to the Arkansas River, then easterly, along the north side of that stream to the western boundary of Kansas. Soon after we reached the Arkansas River, we found the trail of a large party of Indians traveling down the valley. They seemed to be in great haste to get away from us, as they had thrown away their camp kettles, buffalo robes, and everything that might impede their flight. Realizing that the Indians could not be overtaken with the whole command, on account of the poor condition of many of the horses, our officers specially detailed three hundred of our best mounted and best armed men, and sent them forward in pursuit under forced march; but even this plan was unsuccessful, and the pursuit was finally abandoned when near the Kansas line. The term of enlistment of our regiment had already expired, for which reason the command was reluctantly faced about, and the return march to Denver begun.

From the time we left the Sand Creek battleground, it had been very cold and disagreeable. Sharp, piercing winds blew from the north almost incessantly, making us extremely uncomfortable during the day, and even more so at night. Being without tents and compelled to sleep on the open prairie, with no protection whatever from the wind, at times we found the cold almost unbearable. The thin, shoddy government blankets afforded only the slightest possible protection against the bitter winds; consequently those were fortunate indeed who could find a gully in which to make their bed. Our march back to Denver was leisurely and uneventful. We reached there in due course and were mustered out of service on the 29th day of December, 1864. We dispersed to our homes, convinced that we had done a good work and that it needed only a little further punishment of the savages permanently to settle the Indian troubles so far as this Territory was concerned.