An Account of the remarkable occurrences in the life and travels of Colonel James Smith, (late a citizen of Bourbon County, Kentucky,) During his captivity with the Indians, in the years 1755, ’56, ’57, ’58, and ’59.

In which the Customs, Manners, Traditions, Theological Sentiments, Mode of Warfare, Military Tactics, Discipline and Encampments, Treatment of Prisoners, &c. are better explained, and more minutely related, than has been heretofore done by any author on that subject. Together with a description of the Soil, Timber and Waters, where he travelled with the Indians during his captivity. To which is added a brief account of some very uncommon occurrences which transpired after his return from captivity; as well as of the different campaigns carried on against the Indians to the westward of Fort Pitt, since the year 1755, to the present date, 1799. Written by Himself.

James Smith, pioneer, was born in Franklin county, Pennsylvania, in 1737. When he was eighteen years of age he was captured by the Indians, was adopted into one of their tribes, and lived with them as one of themselves until his escape in 1759. He became a lieutenant under General Bouquet during the expedition against the Ohio Indians in 1764, and was captain of a company of rangers in Lord Dunmore’s War. In 1775 he was promoted to major of militia. He served in the Pennsylvania convention in 1776, and in the assembly in 1776-77. In the latter year he was commissioned colonel in command on the frontiers, and performed distinguished services. Smith moved to Kentucky in 1788. He was a member of the Danville convention, and represented Bourbon county for many years in the legislature. He died in Washington county, Kentucky, in 1812. The following narrative of his experience as member of an Indian tribe is from his own book entitled “Remarkable Adventures in the Life and Travels of Colonel James Smith,” printed at Lexington, Kentucky, in 1799. It affords a striking contrast to the terrible experiences of the other captives whose stories are republished in this book; for he was well treated, and stayed so long with his red captors that he acquired expert knowledge of their arts and customs, and deep insight into their character.

Preface

I was strongly urged to publish the following work immediately after my return from captivity, which was nearly forty years ago; but, as at that time the Americans were so little acquainted with Indian affairs, I apprehended a great part of it would be viewed as fable or romance.

As the Indians never attempted to prevent me either from reading or writing, I kept a journal, which I revised shortly after my return from captivity, and which I have kept ever since; and as I have had but a moderate English education, have been advised to employ some person of liberal education to transcribe and embellish it but believing that nature always outshines art, have thought, that occurrences truly and plainly stated, as they happened, would make the best history, be better understood, and most entertaining.

In the different Indian speeches copied into this work, I have not only imitated their own style, or mode of speaking, but have also preserved the ideas meant to be communicated in those speeches. In common conversation I have used my own style, but preserved their ideas. The principal advantage that I expect will result to the public, from the publication of the following sheets, is the observations on the Indian mode of warfare. Experience has taught the Americans the necessity of adopting their mode; and the more perfect we are in that mode, the better we shall be able to defend ourselves against them, when defense is necessary.

James Smith.

Bourbon County, June 1st, 1799.

Introduction

More than thirty years have elapsed since the publication of Col. Smith‘s journal. The only edition ever presented to the public was printed in Lexington, Kentucky, by John Bradford, in 1799. That edition being in pamphlet form, it is presumed that there is not now a dozen entire copies remaining. A new generation has sprung up, and it is believed the time has now arrived, when a second edition, in a more durable form, will be well received by the public. The character of Colonel Smith is well known in the western country, especially amongst the veteran pioneers of Kentucky and Tennessee. He was a patriot in the strictest sense of the word. His whole life was devoted to the service of his country. Raised, as it were, in the wilderness, he received but a limited education; yet nature had endowed him with a vigorous constitution, and a strong and sensible mind; and whether in the camp or the halls of legislation, he gave ample proofs of being, by practice as well as profession, a soldier and a statesman.

During the war of 1811 and 12, being then too old to be serviceable in the field, he made a tender of his experience, and published a treatise on the Indian mode of warfare, with which sad experience had made him so well acquainted. He died shortly afterwards, at the house of a brother-in-law, in Washington County, Kentucky. He was esteemed by all who knew him as an exemplary Christian, and a consistent and unwavering patriot.

By his first marriage, he had several children; and two of his sons, William and James, it is believed, are now living. The name of his first wife is not recollected.

In the year 1785, he intermarried with Mrs. Margaret Irvin, the widow of Mr. Abraham Irvin. Mrs. Irvin was a lady of a highly cultivated mind; and had she lived in more auspicious times, and possessed the advantages of many of her sex, she would have made no ordinary figure as a writer, both in prose and verse. And it may not be uninteresting to the friends of Col. Smith to give a short sketch of her life. Her maiden name was Rodgers. She was born in the year 1744, in Hanover County, Virginia. She was of a respectable family; her father and the Rev. Dr. Rodgers, of New York, were brothers’ children. Her mother was sister to the Rev James Caldwell, who was killed by the British and Tories at Elizabeth Point, New Jersey. Her father removed, when she was a child, to what was then called Lunenburg, now Charlotte County, Virginia. She never went to school but three months, and that at the age of five years. At the expiration of that term the school ceased, and she had no opportunity to attend one afterwards. Her mother, however, being an intelligent woman, and an excellent scholar, gave her lessons at home. On the 5th of November, 1764, she was married to Mr. Irvin, a respectable man, though in moderate circumstances. In the year 1777, when every true friend of his country felt it his duty to render some personal service, he and a neighbor, by the name of William Handy, agreed that they would enlist for the term of three years, and each to serve eighteen months; Irvin to serve the first half, and Handy the second. Mr. Irvin entered upon duty, in company with many others from that section of the country. When they had marched to Dumfries, Virgnia, before they joined the main army, they were ordered to halt, and inoculate for the small-pox. Irvin neglected to inoculate, under the impression he had had the disease during infancy. The consequence was, he took the small-pox in the natural way, and died, leaving Mrs. Irvin, and five small children, four sons and a daughter.

In the fall of 1782, Mrs. Irvin removed, in company with a number of enterprising Virginians, to the wilds of Kentucky; and three years afterwards intermarried with Col. Smith, by whom she had no issue. She died about the year 1800, in Bourbon County, Kentucky, in the 56th year of her age. She was a member of the Presbyterian Church, and sustained through life an unblemished reputation. In early life she wrote but little, most of her productions being the fruits of her mature years, and while she was the wife of Col. Smith. But little of her composition has ever been put to press; but her genius and taste were always acknowledged by those who had access to the productions of her pen. She had a happy talent for pastoral poetry, and many fugitive pieces ascribed to her will long be cherished and admired by the children of song.

Captain Smith’s Narrative

In May, 1755, the province of Pennsylvania agreed to send out three hundred men, in order to cut a wagon road from Fort Loudon, to join Braddock’s road, near the Turkey Foot, or three forks of Yohogania. My brother-in-law, William Smith, Esq. of Conococheague, was appointed commissioner, to have the oversight of these road cutters.

Though I was at that time only eighteen years of age, I had fallen violently in love with a young lady, whom I apprehended was possessed of a large share of both beauty and virtue; but being born between Venus and Mars, I concluded I must also leave my dear fair one, and go out with this company of road cutters, to see the event of this campaign; but still expecting that some time in the course of this summer I should again return to the arms of my beloved.

We went on with the road, without interruption, until near the Alleghany Mountain; when I was sent back, in order to hurry up some provision-wagons that were on the way after us. I proceeded down the road as far as the crossings of Juniata, where, finding the wagons were coming on as fast as possible, I returned up the road again towards the Alleghany Mountain, in company with one Arnold Vigoras. About four or five miles above Bedford, three Indians had made a blind of bushes, stuck in the ground, as though they grew naturally, where they concealed themselves, about fifteen yards from the road. When we came opposite to them, they fired upon us, at this short distance, and killed my fellow traveler, yet their bullets did not touch me; but my horse making a violent start, threw me, and the Indians immediately ran up and took me prisoner. The one that laid hold on me was a Canasatauga, the other two were Delawares. One of them could speak English, and asked me if there were any more white men coming after. I told them not any near that I knew of. Two of these Indians stood by me, whilst the other scalped my comrade; they then set off and ran at a smart rate through the woods, for about fifteen miles, and that night we slept on the Alleghany Mountain, without fire.

The next morning they divided the last of their provision which they had brought from fort Du Quesne, and gave me an equal share, which was about two or three ounces of moldy biscuit; this and a young ground-hog, about as large as a rabbit, roasted, and also equally divided, was all the provision we had until we came to the Loyal Hannan, which was about fifty miles; and a great part of the way we came through exceeding rocky laurel thickets, without any path. When we came to the west side of Laurel hill, they gave the scalp halloo, as usual, which is a long yell or halloo for every scalp or prisoner they have in possession; the last of these scalp halloos were followed with quick and sudden shrill shouts of joy and triumph. On their performing this, we were answered by the firing of a number of guns on the Loyal Hannan, one after another, quicker than one could count, by another party of Indians, who were encamped near where Ligoneer now stands. As we advanced near this party, they increased with repeated shouts of joy and triumph; but I did not share with them in their excessive mirth. When we came to this camp, we found they had plenty of turkeys and other meat there; and though I never before eat venison without bread or salt, yet as I was hungry it relished very well. There we lay that night, and the next morning the whole of us marched on our way for fort Du Quesne. The night after we joined another camp of Indians, with nearly the same ceremony, attended with great noise, and apparent joy, among all except one. The next morning we continued our march, and in the afternoon we came in full view of the fort, which stood on the point, near where fort Pitt now stands. We then made a halt on the bank of the Alleghany, and repeated the scalp halloo, which was answered by the firing of all the firelocks in the hands of both Indians and French who were in and about the fort, in the aforesaid manner, and also the great guns, which were followed by the continued shouts and yells of the different savage tribes who were then collected there.

As I was at this time unacquainted with this mode of firing and yelling of the savages, I concluded that there were thousands of Indians there ready to receive General Braddock; but what added to my surprise, I saw numbers running towards me, stripped naked, excepting breech clouts, and painted in the most hideous manner, of various colors, though the principal color was vermillion, or a bright red; yet there was annexed to this black, brown, blue, &c. As they approached, they formed themselves into two long ranks, about two or three rods apart. I was told by an Indian that could speak English, that I must run betwixt these ranks and that they would flog me all the way as I ran; and if I ran quick, it would be so much the better, as they would quit when I got to the end of the ranks. There appeared to be a general rejoicing around me, yet I could find nothing like joy in my breast; but I started to the race with all the resolution and vigor I was capable of exerting, and found that it was as I had been told, for I was flogged the whole way. When I had got near the end of the lines, I was struck with something that appeared to me to be a stick, or the handle of a tomahawk, which caused me to fall to the ground. On my recovering my senses, I endeavored to renew my race; but as I arose, someone cast sand in my eyes, which blinded me so that I could not see where to run. They continued beating me most intolerably, until I was at length insensible; but before I lost my senses, I remember my wishing them to strike the fatal blow, for I thought they intended killing me, but apprehended they were too long about it.

The first thing I remember was my being in the fort amidst the French and Indians, and a French doctor standing by me, who had opened a vein in my left arm: after which the interpreter asked me how I did; I told him I felt much pain. The doctor then washed my wounds, and the bruised places of my body, with French brandy. As I felt faint, and the brandy smelt well, I asked for some inwardly, but the doctor told me, by the interpreter, that it did not suit my case.

When they found I could speak, a number of Indians came around me, and examined me, with threats of cruel death if I did not tell the truth. The first question they asked me was how many men were there in the party that were coming from Pennsylvania to join Braddock? I told them the truth, that there were three hundred. The next question was, were they well armed? I told them they were all well armed, (meaning the arm of flesh,) for they had only about thirty guns among the whole of them; which if the Indians had known, they would certainly have gone and cut them all off; therefore, I could not in conscience let them know the defenseless situation of these road cutters. I was then sent to the hospital, and carefully attended by the doctors, and recovered quicker than what I expected.

Sometime after I was there, I was visited by the Delaware Indian already mentioned, who was at the taking of me, and could speak some English. Though he spoke but bad English, yet I found him to be a man of considerable understanding. I asked him if I had done anything that had offended the Indians which caused them to treat me so unmercifully. He said no; it was only an old custom the Indians had, and it was like how do you do; after that, he said, I would be well used. I asked him if I should be admitted to remain with the French. He said no; and told me that, as soon as I recovered, I must not only go with the Indians, but must be made an Indian myself. I asked him what news from Braddock’s army. He said the Indians spied them every day, and he showed me, by making marks on the ground with a stick, that Braddock‘s army was advancing in very close order, and that the Indians would surround them, take trees, and (as he expressed it) shoot um down all one pigeon.

Shortly after this, on the 9th day of July, 1755, in the morning, I heard a great stir in the fort. As I could then walk with a staff in my hand, I went out of the door, which was just by the wall of the fort, and stood upon the wall, and viewed the Indians in a huddle before the gate, where were barrels of powder, bullets, flints, &c., and every one taking what suited. I saw the Indians also march off in rank entire; likewise the French Canadians, and some regulars. After viewing the Indians and French in different positions, I computed them to be about four hundred, and wondered that they attempted to go out against Braddock with so small a party. I was then in high hopes that I would soon see them fly before the British troops, and that General Braddock would take the fort and rescue me.

I remained anxious to know the event of this day; and, in the afternoon, I again observed a great noise and commotion in the fort, and though at that time I could not understand French, yet I found that it was the voice of joy and triumph, and feared that they had received what I called bad news.

I had observed some of the old country soldiers speak Dutch: as I spoke Dutch, I went to one of them, and asked him what was the news. He told me that a runner had just arrived, who said that Braddock would certainly be defeated that the Indians and French had surrounded him, and were concealed behind trees and in gullies, and kept a constant fire upon the English, and that they saw the English falling in heaps, and if they did not take the river, which was the only gap, and make their escape, there would not be one man left alive before sundown. Sometime after this I heard a number of scalp halloos, and saw a company of Indians and French coming in. I observed they had a great many bloody scalps, grenadiers’ caps, British canteens, bayonets, &c. with them. They brought the news that Braddock was defeated. After that another company came in, which appeared to be about one hundred, and chiefly Indians, and it seemed to me that almost every one of this company was carrying scalps; after this came another company with a number of wagon horses, and also a great many scalps. Those that were coming in, and those that had arrived, kept a constant firing of small arms, and also the great guns in the fort, which were accompanied with the most hideous shouts and yells from all quarters; so that it appeared to me as if the infernal regions had broke loose.

About sundown I beheld a small party coming in with about a dozen prisoners, stripped naked, with their hands tied behind their backs, and their faces and part of their bodies blacked; these prisoners they burned to death on the bank of Alleghany River, opposite to the fort. I stood on the fort wall until I beheld them begin to burn one of these men; they had him tied to a stake, and kept touching him with firebrands, red-hot irons, &c., and he screamed in a most doleful manner; the Indians, in the mean time, yelling like infernal spirits.

As this scene appeared too shocking for me to behold, I retired to my lodgings both sore and sorry.

When I came into my lodgings I saw Russel‘s Seven Sermons, which they had brought from the field of battle, which a Frenchman made a present to me. From the best information I could receive, there were only seven Indians and four French killed in this battle, and five hundred British lay dead in the field, besides what were killed in the river on their retreat.

The morning after the battle I saw Braddock‘s artillery brought into the fort; the same day I also saw several Indians in British officers’ dress, with sash, half moon, laced hats, &c., which the British then wore.

A few days after this the Indians demanded me, and I was obliged to go with them. I was not yet well able to march, but they took me in a canoe up the Alleghany River to an Indian town, that was on the north side of the river, about forty miles above fort Du Quesne. Here I remained about three weeks, and was then taken to an Indian town on the west branch of Muskingum, about twenty miles above the forks, which was called Tullihas, inhabited by Delawares, Caughnewagas, and Mohicans. On our route betwixt the aforesaid towns the country was chiefly black oak and white oak land, which appeared generally to be good wheat land, chiefly second and third rate, intermixed with some rich bottoms.

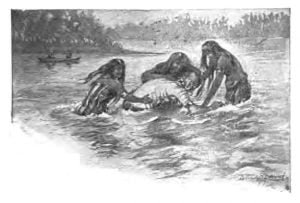

The day after my arrival at the aforesaid town, a number of Indians collected about me, and one of them began to pull the hair out of my head. He had some ashes on a piece of bark, in which he frequently dipped his fingers, in order to take the firmer hold, and so he went on, as if he had been plucking a turkey, until he had all the hair clean out of my head, except a small spot about three or four inches square on my crown; this they cut off with a pair of scissors, excepting three locks, which they dressed up in their own mode. Two of these they wrapped round with a narrow beaded garter made by themselves for that purpose, and the other they plaited at full length, and then stuck it full of silver brooches. After this they bored my nose and ears, and fixed me off with ear-rings and nose jewels; then they ordered me to strip off my clothes and put on a breech-clout, which I did; they then painted my head, face, and body, in various colors. They put a large belt of wampum on my neck, and silver bands on my hands and right arm; and so an old chief led me out in the street, and gave the alarm halloo, coo-wigh, several times repeated quick; and on this, all that were in the town came running and stood round the old chief, who held me by the hand in the midst. As I at that time knew nothing of their mode of adoption, and had seen them put to death all they had taken, and as I never could find that they saved a man alive at Braddock’s defeat, I made no doubt but they were about putting me to death in some cruel manner. The old chief, holding me by the hand, made a long speech, very loud, and when he had done, he handed me to three young squaws, who led me by the hand down the bank, into the river, until the water was up to our middle. The squaws then made signs to me to plunge myself into the water, but I did not understand them; I thought that the result of the council was that I should be drowned, and that these young ladies were to be the executioners. They all three laid violent hold of me, and I for some time opposed them with all my might, which occasioned loud laughter by the multitude that were on the bank of the river. At length one of the squaws made out to speak a little English, (for I believe they began to be afraid of me, and said no hurt you.) On this I gave myself up to their ladyships, who were as good as their word; for though they plunged me under water, and washed and rubbed me severely, yet I could not say they hurt me much.

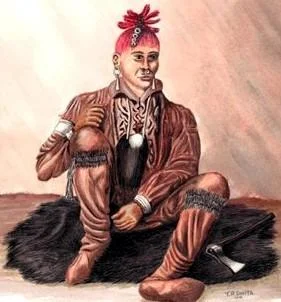

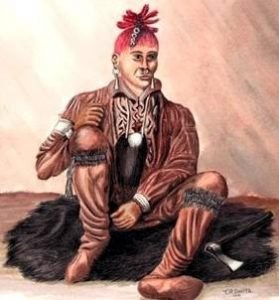

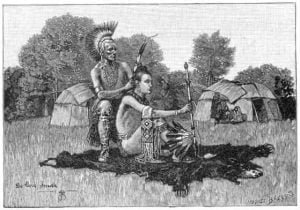

These young women then led me up to the council house, where some of the tribe were ready with new clothes for me. They gave me a new ruffled shirt, which I put on, also a pair of leggins done off with ribbons and beads, likewise a pair of moccasins, and garters dressed with beads, porcupine quills, and red hair also a tinsel laced cappo. They again painted my head and face with various colors, and tied a bunch of red feathers to one of those locks they had left on the crown of my head, which stood up five or six inches. They seated me on a bearskin, and gave me a pipe, tomahawk, and polecat-skin pouch, which had been skinned pocket fashion, and contained tobacco, killegenico, or dry sumach leaves, which they mix with their tobacco; also spunk, flint, and steel. When I was thus seated, the Indians came in dressed and painted in their grandest manner. As they came in they took their seats, and for a considerable time there was a profound silence everyone was smoking; but not a word was spoken among them. At length one of the chiefs made a speech, which was delivered to me by an interpreter, and was as, followeth: “My son, you are now flesh of our flesh, and bone of our bone. By the ceremony which was performed this day every drop of white blood was washed out of your veins; you are taken into the Caughnewago nation, and initiated into a warlike tribe; you are adopted into a great family, and now received with great seriousness and solemnity in the room and place of a great man. After what has passed this day, you are now one of us by an old strong law and custom. My son, you have now nothing to fear we are now under the same obligations to love, support, and defend you that we are to love and to defend one another; therefore, you are to consider yourself as one of our people.” At this time I did not believe this fine speech, especially that of the white blood being washed out of me; but since that time I have found that there was much sincerity in said speech; for, from that day, I never knew them to make any distinction between me and themselves in any respect whatever until I left them. If they had plenty of clothing, I had plenty; if we were scarce, we all shared one fate.

After this ceremony was over, I was introduced to my new kin, and told that I was to attend a feast that evening, which I did. And as the custom was, they gave me also a bowl and wooden spoon, which I carried with me to the place, where there was a number of large brass kettles full of boiled venison and green corn; every one advanced with his bowl and spoon, and had his share given him. After this, one of the chiefs made a short speech, and then we began to eat.

The name of one of the chiefs in this town was Tecanyate-righto, alias Pluggy and the other Asallecoa, alias Mohawk Solomon. As Pluggy and his party were to start the next day to war, to the frontiers of Virginia, the next thing to be performed was the war dance, and their war songs. At their war dance they had both vocal and instrumental music; they had a short hollow gum, closed at one end, with water in it, and parchment stretched over the open end thereof, which they beat with one stick, and made a sound nearly like a muffled drum. All those who were going on this expedition collected together and formed. An old Indian then began to sing, and timed the music by beating on this drum, as the ancients formerly timed their music by beating the tabor. On this the warriors began to advance, or move forward in concert, like well-disciplined troops would march to the fife and drum. Each warrior had a tomahawk, spear, or war-mallet in his hand and they all moved regularly towards the east, or the way they intended to go to war. At length they all stretched their tomahawks towards the Potomac, and giving a hideous shout or yell; they wheeled quick about, and danced in the same manner back. The next was the war song. In performing this, only one sung at a time, in a moving posture, with a tomahawk in his hand, while all the other warriors were engaged in calling aloud he-uh, he-uh, which they constantly repeated while the war song was going on. When the warrior that was singing had ended his song, he struck a war post with his tomahawk, and with a loud voice told what warlike exploits he had done, and what he now intended to do, which were answered by the other warriors with loud shouts of applause. Some who had not before intended to go to war, at this time, were so animated by this performance that they took up the tomahawk and sung the war song, which was answered with shouts of joy, as they were then initiated into the present marching company. The next morning this company all collected at one place, with their heads and faces painted with various colors, and packs upon their backs; they marched off, all silent, except the commander, who, in the front, sung the travelling song, which began in this manner: hoo caughtainte heegana. Just as the rear passed the end of the town, they began to fire in their slow manner, from the front to the rear, which was accompanied with shouts and yells from all quarters.

This evening I was invited to another sort of dance, which was a kind of promiscuous dance. The young men stood in one rank, and the young women in another, about one rod apart, facing each other. The one that raised the tune, or started the song, held a small gourd or dry shell of a squash in his hand, which contained beads or small stones, which rattled. When he began to sing, he timed the tune with his rattle; both men and women danced and sang together, advancing towards each other, stooping until their heads would be touching together, and then ceased from dancing, with loud shouts, and retreated and formed again, and so repeated the same thing over and over, for three or four hours, without intermission. This exercise appeared to me at first irrational and insipid; but I found that in singing their tunes they used ya ne no hoo wa ne, &c., like our fa sol la, and though they have no such thing as jingling verse, yet they can intermix sentences with their notes, and say what they please to each other, and carry on the tune in concert. I found that this was a kind of wooing or courting dance, and as they advanced stooping with their heads together, they could say what they pleased in each other’s ear, without disconcerting their rough music, and the others, or those near, not hear what they said.

Shortly after this I went out to hunt, in company with Mohawk Solomon, some of the Caughnewagas, and a Delaware Indian, that was married to a Caughnewaga squaw. We travelled about south from this town, and the first night we killed nothing, but we had with us green corn, which we roasted and ate that night. The next day we encamped about twelve o’clock, and the hunters turned out to hunt, and I went down the run that we encamped on, in company with some squaws and boys, to hunt plums, which we found in great plenty. On my return to camp I observed a large piece of fat meat; the Delaware Indian, that could talk some English, observed me looking earnestly at this meat, and asked me, what meat you think that is? I said I supposed it was bear meat; he laughed, and said, ho, all one fool you, beal now elly pool, and pointing to the other side of the camp, he said, look at that skin, you think that beal skin? I went and lifted the skin, which appeared like an ox-hide; he then said, what skin you think that? I replied, that I thought it was a buffalo hide; he laughed, and said, you fool again, you know nothing, you think buffalo that colo? I acknowledged I did not know much about these things, and told him I never saw a buffalo, and that I had not heard what color they were. He replied, by and by you shall see gleat many buffalo; he now go to gleat lick. That skin no buffalo skin, that skin buck-elk skin. They went out with horses, and brought in the remainder of this buck-elk, which was the fattest creature I ever saw of the tallow kind.

We remained at this camp about eight or ten days, and killed a number of deer. Though we had neither bread nor salt at this time, yet we had both roast and boiled meat in great plenty, and they were frequently inviting me to eat when I had no appetite.

We then moved to the buffalo lick, where we killed several buffalo, and in their small brass kettles they made about half a bushel of salt. I suppose this lick was about thirty or forty miles from the aforesaid town, and somewhere between the Muskingum, Ohio, and Sciota. About the lick was clear, open woods, and thin white oak land, and at that time there were large roads leading to the lick, like wagon roads. We moved from this lick about six or seven miles, and encamped on a creek.

Though the Indians had given me a gun, I had not yet been admitted to go out from the camp to hunt. At this place Mohawk Solomon asked me to go out with him to hunt, which I readily agreed to. After some time we came upon some fresh buffalo tracks. I had observed before this that the Indians were upon their guard, and afraid of an enemy; for, until now, they and the southern nations had been at war. As we were following the buffalo tracks, Solomon seemed to be upon his guard, went very slow, and would frequently stand and listen, and appeared to be in suspense. We came to where the tracks were very plain in the sand, and I said it is surely buffalo tracks; he said, hush, you know nothing, may be buffalo tracks, may be Catawba. He went very cautious until we found some fresh buffalo dung; he then smiled, and said, Catawba cannot make so. He then stopped, and told me an odd story about the Catawbas. He said that formerly the Catawbas came near one of their hunting camps, and at some distance from the camp lay in ambush; and in order to decoy them out, sent two or three Catawbas in the night past their camp, with buffalo hoofs fixed on their feet, so as to make artificial tracks. In the morning, those in the camp followed after these tracks, thinking they were buffalo, until they were fired on by the Catawbas, and several of them killed. The others fled, collected a party and pursued the Catawbas; but they, in their subtilty, brought with them rattlesnake poison, which they had collected from the bladder that lieth at the root of the snake’s teeth; this they had corked up in a short piece of a cane-stalk. They had also brought with them small cane or reed, about the size of a rye-straw, which they made sharp at the end like a pen, and dipped them in this poison, and stuck them in the ground among the grass, along their own tracks, in such a position that they might stick into the legs of the pursuers, which answered the design; and as the Catawbas had runners behind to watch the motion of the pursuers, when they found that a number of them were lame, being artificially snake bit, and that they were all turning back, the Catawbas turned upon the pursuers, and defeated them, and killed and scalped all those that were lame. When Solomon had finished this story, and found that I understood him, he concluded by saying, you don’t know, Catawba velly bad Indian, Catawba all one devil Catawba.

Sometime after this, I was told to take the dogs with me, and go down the creek, perhaps I might kill a turkey; it being in the afternoon, I was also told not to go far from the creek, and to come up the creek again to the camp, and to take care not to get lost. When I had gone some distance down the creek, I came upon fresh buffalo tracks, and as I had a number of dogs with me to stop the buffalo, I concluded I would follow after and kill one; and as the grass and weeds were rank, I could readily follow the track. A little before sundown I despaired of coming up with them. I was then thinking how I might get to camp before night. I concluded, as the buffalo had made several turns, if I look the track back to the creek it would be dark before I could get to camp; therefore I thought I would take a near way through the hills, and strike the creek a little below the camp; but as it was cloudy weather, and I a very young woodsman, I could find neither creek nor camp. When night came on I fired my gun several times, and hallooed, but could have no answer. The next morning early, the Indians were out after me, and as I had with me ten or a dozen dogs, and the grass and weeds rank, they could readily follow my track. When they came up with me, they appeared to be in very good humor. I asked Solomon if he thought I was running away; he said, no, no, you go too much cloaked. On my return to camp they took my gun from me, and for this rash step I was reduced to a bow and arrows, for near two years. We were out on this tour for about six weeks.

This country is generally hilly, though intermixed with considerable quantities of rich upland, and some good bottoms.

When we returned to the town, Pluggy and his party had arrived, and brought with them a considerable number of scalps and prisoners from the south branch of the Potomac; they also brought with them an English Bible, which they gave to a Dutch woman who was a prisoner; but as she could not read English, she made a present of it to me, which was very acceptable.

I remained in this town until sometime in October, when my adopted brother, called Tontileaugo, who had married a Wyandot squaw, took me with him to Lake Erie. We proceeded up the west branch of Muskingum, and for some distance up the river the land was hilly, but intermixed with largo bodies of tolerable rich upland, and excellent bottoms. We proceeded on to the head waters of the west branch of Muskingum. On the head waters of this branch, and from thence to the waters of Canesadooharie, there is a large body of rich, well lying land; the timber is ash, walnut, sugar tree, buckeye, honey-locust, and cherry, intermixed with some oak, hickory, &c. This tour was at the time that the black haws were ripe, and we were seldom out of sight of them; they were common here both in the bottoms and upland.

On this route we had no horses with us, and when we started from the town all the pack I carried was a pouch containing my books, a little dried venison, and my blanket. I had then no gun, but Tontileaugo, who was a first rate hunter, carried a rifle gun, and every day killed deer, raccoons, or bears. We left the meat, excepting a little for present use, and carried the skins with us until we encamped, and then stretched them with elm bark, in a frame made with poles stuck in the ground, and tied together with lynn or elm bark; and when the skins were dried by the fire, we packed them up and carried them with us the next day.

As Tontileaugo could not speak English, I had to make use of all the Caughnewaga I had learned, even to talk very imperfectly with him; but I found I learned to talk Indian faster this way than when I had those with me who could speak English.

As we proceeded down the Canesadooharie waters, our packs increased by the skins that were daily killed, and became so very heavy that we could not march more than eight or ten miles per day. We came to Lake Erie about six miles west of the mouth of Canesadooharie. As the wind was very high the evening we came to the lake, I was surprised to hear the roaring of the water, and see the high waves that dashed against the shore, like the ocean. We encamped on a run near the lake, and as the wind fell that night, the next morning the lake was only in a moderate motion, and we marched on the sand along the side of the water, frequently resting ourselves, as we were heavily laden. I saw on the sand a number of large fish, that had been left in flat or hollow places; as the wind fell and the waves abated, they were left without water, or only a small quantity; and numbers of bald and grey eagles, &c., were along the shore devouring them.

Sometime in the afternoon we came to a large camp of Wyandots, at the mouth of Canesadooharie, where Tontileaugo’s wife was. Here we were kindly received; they gave us a kind of rough, brown potatoes, which grew spontaneously, and were called by the Caughnewagas ohnenata. These potatoes peeled and dipped in raccoon’s fat taste nearly like our sweet potatoes. They also gave us what they call caneheanta, which is a kind of hominy, made of green corn, dried, and beans, mixed together.

From the head waters of Canesadooharie to this place, the land is generally good; chiefly first or second rate, and, comparatively, little or no third rate. The only refuse is some swamps that appear to be too wet for use, yet I apprehend that a number of them, if drained, would make excellent meadows. The timber is black oak, walnut, hickory, cherry, black ash, white ash, water ash, buckeye, black-locust, honey-locust, sugar-tree, and elm. There is also some land, though comparatively but small, where the timber is chiefly white oak, or beech; this may be called third rate. In the bottoms, and also many places in the upland, there is a large quantity of wild apple, plum, and red and black haw trees. It appeared to be well watered, and a plenty of meadow ground, intermixed with upland, but no large prairies or glades that I saw or heard of. In this route deer, bear, turkeys, and raccoons appeared plenty, but no buffalo, and very little sign of elks.

We continued our camp at the mouth of Canesadooharie for some time, where we killed some deer, and a great many raccoons; the raccoons here were remarkably large and fat. At length we all embarked in a large birch bark canoe. This vessel was about four feet wide, and three feet deep, and about five and thirty feet long; and though it could carry a heavy burden, it was so artfully and curiously constructed, that four men could carry it several miles, or from one landing place to another, or from the waters of the lake to the waters of the Ohio. We proceeded up Canesadooharie a few miles, and went on shore to hunt; but to my great surprise they carried the vessel we all came in up the bank, and inverted it or turned the bottom up, and converted it to a dwelling-house, and kindled a fire before us to warm ourselves by and cook. With our baggage and ourselves in this house we were very much crowded, yet our little house turned off the rain very well.

We kept moving and hunting up this river until we came to the falls; here we remained some weeks, and killed a number of deer, several bears, and a great many raccoons. From the mouth of this river to the falls is about five and twenty miles. On our passage up I was not much out from the river but what I saw was good land, and not hilly.

About the falls is thin chesnut land, which is almost the only chesnut timber I ever saw in this country.

While we remained here I left my pouch with my books in camp, wrapt up in my blanket, and went out to hunt chesnuts. On my return to camp my books were missing. I inquired after them, and asked the Indians if they knew where they were; they told me that they supposed the puppies had carried them off. I did not believe them, but thought they were displeased at my poring over my books, and concluded that they had destroyed them, or put them out of my way.

After this I was again out after nuts, and on my return beheld a new erection, composed of two white oak saplings, that were forked about twelve feet high, and stood about fifteen feet apart. They had cut these saplings at the forks, and laid a strong pole across, which appeared in the form of a gallows, and the poles they had shaved very smooth, and painted in places with vermillion. I could not conceive the use of this piece of work, and at length concluded it was a gallows. I thought that I had displeased them by reading my books, and that they were about putting me to death. The next morning I observed them bringing their skins all to this place, and hanging them over this pole, so as to preserve them from being injured by the weather. This removed my fears. They also buried their large canoe in the ground, which is the way they took to preserve this sort of a canoe in the winter season.

As we had at this time no horse, everyone got a pack on his back, and we steered an east course about twelve miles and encamped. The next morning we proceeded on the same course about ten miles to a large creek that empties into Lake Erie, betwixt Canesadooharie and Cayahaga. Here they made their winter cabin in the following form: they cut logs about fifteen feet long, and laid these logs upon each other, and drove posts in the ground at each end to keep them together; the posts they tied together at the top with bark, and by this means raised a wall fifteen feet long, and about four feet high, and in the same manner they raised another Avail opposite to this, at about twelve feet distance; then they drove forks in the ground in the centre of each end, and laid a strong pole from end to end on these forks; and from these walls to the poles, they set up poles instead of rafters, and on these they tied small poles in place of laths; and a cover was made of lynn bark, which will run even in the winter season.

As every tree will not run, they examine the tree first, by trying it near the ground, and when they find it will do they fell the tree, and raise the bark with the tomahawk, near the top of the tree, about five or six inches broad, then put the tomahawk handle under this bark, and pull it along down to the butt of the tree; so that sometimes one piece of bark will be thirty feet long. This bark they cut at suitable lengths in order to cover the hut.

At the end of these walls they set up split timber, so that they had timber all round, excepting a door at each end. At the top, in place of a chimney, they left an open place, and for bedding they laid down the aforesaid kind of bark, on which they spread bear-skins. From end to end of this hut along the middle there were fires, which the squaws made of dry split wood, and the holes or open places that appeared the squaws stopped with moss, which they collected from old logs; and at the door they hung a bear-skin; and notwithstanding the winters are hard here, our lodging was much better than what I expected.

It was some time in December when we finished this winter cabin; but when we had got into this comparatively fine lodging, another difficulty arose, we had nothing to eat. While I was travelling with Tontileaugo, as was before mentioned, and had plenty of fat venison, bear’s meat and raccoons, I then thought it was hard living without bread or salt; but now I began to conclude, that if I had anything that would banish pinching hunger, and keep soul and body together, I would be content.

While the hunters were all out, exerting themselves to the utmost of their ability, the squaws and boys (in which class I was) were scattered out in the bottoms, hunting red haws, black haws and hickory nuts. As it was too late in the year, we did not succeed in gathering haws; but we had tolerable success in scratching up hickory nuts from under a light snow, which we carried with us lest the hunters should not succeed. After our return the hunters came in, who had killed only two small turkeys, which were but little among eight hunters and thirteen squaws, boys, and children; but they were divided with the greatest equity and justice everyone got their equal share.

The next day the hunters turned out again, and killed one deer and three bears.

One of the bears was very large and remarkably fat. The hunters carried in meat sufficient to give us all a hearty supper and breakfast.

The squaws and all that could carry turned out to bring in meat, everyone had their share assigned them, and my load was among the least; yet, not being accustomed to carrying in this way, I got exceeding weary, and told them my load was too heavy, I must leave part of it and come for it again. They made a halt and only laughed at me, and took part of my load and added it to a young squaw’s, who had as much before as I carried.

This kind of reproof had a greater tendency to excite me to exert myself in carrying without complaining than if they had whipped me for laziness. After this the hunters held a council, and concluded that they must have horses to carry their loads; and that they would go to war even in this inclement season, in order to bring in horses.

Tontileaugo wished to be one of those who should go to war; but the votes went against him, as he was one of our best hunters; it was thought necessary to leave him at this winter camp to provide for the squaws and children. It was agreed upon that Tontileaugo and three others should stay and hunt, and the other four go to war.

They then began to go through their common ceremony. They sung their war songs, danced their war dances, &c. And when they were equipped they went off singing their marching song, and firing their guns. Our camp appeared to be rejoicing; but I was grieved to think that some innocent persons would be murdered, not thinking of danger.

After the departure of these warriors we had hard times; and though we were not altogether out of provisions, we were brought to short allowance. At length Tontileaugo had considerable success, and we had meat brought into camp sufficient to last ten days. Tontileaugo then took me with him in order to encamp some distance from this winter cabin, to try his luck there. We carried no provisions with us; he said he would leave what was there for the squaws and children, and that we could shift for ourselves. We steered about a south course up the waters of this creek, and encamped about ten or twelve miles from the winter cabin. As it was still cold weather and a crust upon the snow, which made a noise as we walked, and alarmed the deer, we could kill nothing, and consequently went to sleep without supper. The only chance we had under these circumstances was to hunt bear holes; as the bears about Christmas search out a winter lodging place, where they lie about three or four months without eating or drinking. This may appear to some incredible; but it is well known to be the case by those who live in the remote western parts of North America.

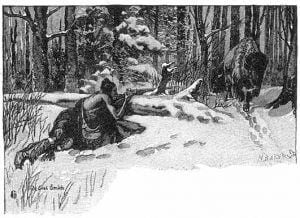

The next morning early we proceeded on, and when we found a tree scratched by the bears climbing up, and the hole in the tree sufficiently large for the reception of the bear, we then felled a sapling or small tree against or near the hole; and it was my business to climb up and drive out the bear while Tontileaugo stood ready with his gun and bow. We went on in this manner until evening, without success. At length we found a large elm scratched, and a hole in it about forty feet up; but no tree nigh, suitable to lodge against the hole. Tontileaugo got a long pole and some dry rotten wood, which he tied in bunches, with bark; and as there was a tree that grew near the elm, and extended up near the hole, but leaned the wrong way, so that we could not lodge it to advantage, to remedy this inconvenience, he climbed up this tree and carried with him his rotten wood, fire and pole. The rotten wood he tied to his belt, and to one end of the pole he tied a. hook and a piece of rotten wood, which he set fire to, as it would retain fire almost like spunk, and reached this hook from limb to limb as he went up. When he got up with his pole he put dry wood on fire into the hole; after he put in the fire he heard the bear snuff, and he came speedily down, took his gun in his hand, and waited until the bear would come out; but it was some time before it appeared, and when it did appear he attempted taking sight with his rifle; but it being then too dark to see the sights, he set it down by a tree, and instantly bent his bow, took hold of an arrow, and shot the bear a little behind the shoulder. I was preparing also to shoot an arrow, but he called to me to stop, there was no occasion; and with that the bear fell to the ground.

Being very hungry, we kindled a fire, opened the bear, took out the liver, and wrapped some of the caul fat round, and put it on a wooden spit, which we stuck in the ground by the fire to roast; then we skinned the bear, got on our kettle, and had both roast and boiled, and also sauce to our meat, which appeared to me to be delicate fare. After I was fully satisfied I went to sleep; Tontileaugo awoke me, saying, come, eat hearty, we have got meat plenty now.

The next morning we cut down a lynn tree, peeled bark and made a snug little shelter, facing the southeast, with a large log betwixt us and the northwest; we made a good fire before us, and scaffolded up our meat at one side. When we had finished our camp we went out to hunt, searched two trees for bears, but to no purpose. As the snow thawed a little in the afternoon, Tontileaugo killed a deer, which we carried with us to camp.

The next day we turned out to hunt, and near the camp we found a tree well scratched; but the hole was above forty feet high, and no tree that we could lodge against the hole; but finding that it was very hollow, we concluded that we could cut down the tree with our tomahawks, which kept us working a considerable part of the day. When the tree fell we ran up, Tontileaugo with his gun and bow, and I with my bow ready bent. Tontileaugo shot the bear through with his rifle, a little behind the shoulders; I also shot, but too far back; and not being then much accustomed to the business, my arrow penetrated only a few inches through the skin. Having killed an old she bear and three cubs, we hauled her on the snow to the camp, and only had time afterwards to get wood, make a fire, cook, &c., before dark.

Early the next morning we went to business, searched several trees, but found no bears. On our way home we took three raccoons out of a hollow elm, not far from the ground.

We remained here about two weeks, and in this time killed four bears, three deer, several turkeys and a number of raccoons. We packed up as much meat as we could carry, and returned to our winter cabin. On our arrival there was great joy, as they were all in a starving condition, the three hunters that we had left having killed but very little. All that could carry a pack, repaired to our camp to bring in meat.

Sometime in February the four warriors returned, who had taken two scalps and six horses from the frontiers of Pennsylvania. The hunters could then scatter out a considerable distance from the winter cabin and encamp, kill meat, and bring it in upon horses; so that we commonly after this had plenty of provision.

In this month we began to make sugar. As some of the elm bark will strip at this season, the squaws, after finding a tree that would do, cut it down, and with a crooked stick, broad and sharp at the end, took the bark off the tree, and of this bark made vessels in a curious manner, that would hold about two gallons each: they made above one hundred of these kind of vessels, In the sugar tree they cut a notch, sloping down, and at the end of the notch stuck in a tomahawk; in the place where they stuck the tomahawk they drove a long chip, in order to carry the water out from the tree, and under this they set their vessel to receive it. As sugar trees were plenty and large here, they seldom or never notched a tree that was not two or three feet over. They also made bark vessels for carrying the water that would hold about four gallons each. They had two brass kettles, that held about fifteen gallons each, and other smaller kettles in which they boiled the water. But as they could not at times boil away the water as fast as it was collected, they made vessels of bark, that would hold about one hundred gallons each, for retaining the water; and though the sugar trees did not run every day, they had always a sufficient quantity of water to keep them boiling during the whole sugar season.

The way we commonly used our sugar while encamped was by putting it in bear’s fat until the fat was almost as sweet as the sugar itself, and in this we dipped our roasted venison. About this time some of the Indian lads and myself were employed in making and attending traps for catching raccoons, foxes, wildcats, &c.

As the raccoon is a kind of water animal, that frequents the runs, or small water courses, almost the whole night, we made our traps on the runs, by laying one small sapling on another, and driving in posts to keep them from rolling. The under sapling we raised about eighteen inches, and set so that on the raccoon’s touching a string, or a small piece of bark, the sapling would fall and kill it; and lest the raccoon should pass by, we laid brush on both sides of the run, only leaving the channel open.

The fox traps we made nearly in the same manner, at the end of a hollow log, or opposite to a hole at the root of a hollow tree, and put venison on a stick for bait; we had it so set that when the fox took hold of the meat the trap fell. While the squaws were employed in making sugar, the boys and men were engaged in hunting and trapping.

About the latter end of March, we began to prepare for moving into town, in order to plant corn. The squaws were then frying the last of their bear’s fat, and making vessels to hold it: the vessels were made of deer-skins, which were skinned by pulling the skin off the neck, without ripping. After they had taken off the hair, they gathered it in small plaits round the neck and with a string drew it together like a purse; in the centre a pin was put, below which they tied a string, and while it was wet they blew it up like a bladder, and let it remain in this manner until it was dry, when it appeared nearly in the shape of a sugar loaf, but more rounding at the lower end. One of these vessels would hold about four or five gallons. In these vessels it was they carried their bear’s oil.

When all things were ready, we moved back to the falls of Canesadooharie. In this route the land is chiefly first and second rate; but too much meadow ground, in proportion to the upland. The timber is white ash, elm, black oak, cherry, buckeye, sugar tree, lynn, mulberry, beech, white oak, hickory, wild apple tree, red haw, black haw, and spicewood bushes. There is in some places spots of beech timber, which spots may be called third rate land. Buckeye, sugar tree and spicewood are common in the woods here. There is in some places large swamps too wet for any use.

On our arrival at the falls, (as we had brought with us on horseback about two hundred weight of sugar, a large quantity of bear’s oil, skins, &c.,) the canoe we had buried was not sufficient to carry all; therefore we were obliged to make another one of elm bark. While we lay here, a young Wyandot found my books. On this they collected together; I was a little way from the camp, and saw the collection, but did not know what it meant. They called me by my Indian name, which was Scoouwa, repeatedly. I ran to see what was the matter; they showed me my books, and said they were glad they had been found, for they knew I was grieved at the loss of them, and that they now rejoiced with me because they were found. As I could then speak some Indian, especially Caughnewaga, (for both that and the Wyandot tongue were spoken in this camp,) I told them that I thanked them for the kindness they had always shown to me, and also for finding my books. They asked if the books were damaged. I told them not much. They then showed how they lay, which was in the best manner to turn off the water. In a deer-skin pouch they lay all winter. The print was not much injured, though the binding was. This was the first time that I felt my heart warm towards the Indians. Though they had been exceedingly kind to me, I still before detested them, on account of the barbarity I beheld after Braddock‘s defeat. Neither had I ever before pretended kindness, or expressed myself in a friendly manner; but I began now to excuse the Indians on account of their want of information.

When we were ready to embark, Tontileaugo would not go to town, but go up the river, and take a hunt. He asked me if I choose to go with him. I told him I did. We then got some sugar, bear’s oil bottled up in a bear’s gut, and some dry venison, which we packed up, and went up Canesadooharie, about thirty miles, and encamped. At this time I did not know either the day of the week or the month; but I supposed it to be about the first of April. We had considerable success in our business. We also found some stray horses, or a horse, mare, and a young colt; and though they had run in the woods all winter, they were in exceeding good order. There is plenty of grass here all winter, under the snow, and horses accustomed to the woods can work it out. These horses had run in the woods until they were very wild.

Tontileaugo one night concluded that we must run them down. I told him I thought we could not accomplish it. He said he had run down bears, buffaloes, and elks; and in the great plains, with only a small snow on the ground, he had run down a deer; and he thought that in one whole day he could tire or run down any four-footed animal except a wolf. I told him that though a deer was the swiftest animal to run a short distance, yet it would tire sooner than a horse. He said he would at all events try the experiment. He had heard the Wyandots say that I could run well, and now he would see whether I could or not. I told him that I never had run all day, and of course was not accustomed to that way of running. I never had run with the Wyandots more than seven or eight miles at one time. He said that was nothing, we must either catch these horses or run all day.

In the morning early we left camp, and about sunrise we started after them, stripped naked excepting breech-clouts and moccasins. About ten o’clock I lost sight of both Tontileaugo and the horses, and did not see them again until about three o’clock in the afternoon. As the horses run all day in about three or four miles square, at length they passed where I was, and I fell in close after them. As I then had a long rest. I endeavored to keep ahead of Tontileaugo, and after some time I could hear him after me calling chakoh, chakoanaugh, which signifies, pull away or do your best. We pursued on, and after some time Tontileaugo passed me, and about an hour before sundown we despaired of catching these horses, and returned to camp, where we had left our clothes.

I reminded Tontileaugo of what I had told him; he replied he did not know what horses could do. They are wonderful strong to run; but withal we made them very tired. Tontileaugo then concluded he would do as the Indians did with wild horses when out at war: which is to shoot them through the neck under the mane, and above the bone, which will cause them to fall and lie until they can halter them, and then they recover again. This he attempted to do; but as the mare was very wild, he could not get sufficiently nigh to shoot her in the proper place; however, he shot, the ball passed too low, and killed her. As the horse and colt stayed at this place, we caught the horse, and took him and the colt with us to camp.

We stayed at this camp about two weeks, and killed a number of bears, raccoons, and some beavers. We made a canoe of elm bark, and Tontileaugo embarked in it. He arrived at the falls that night; whilst I, mounted on horseback, with a bear-skin saddle and bark stirrups, proceeded by land to the falls. I came there the next morning, and we carried our canoe and loading past the falls.

The river is very rapid for some distance above the falls, which are about twelve or fifteen feet, nearly perpendicular. This river, called Canesadooharie, interlocks with the West Branch of Muskingum, runs nearly a north course, and empties into the south side of Lake Erie, about eight miles east from Sandusky, or betwixt Sandusky and Cayahaga.

On this last route the land is nearly the same as that last described, only there is not so much swampy or wet ground.

We again proceeded towards the lake, I on horseback, and Tontileaugo by water. Here the land is generally good, but I found some difficulty in getting round swamps and ponds. When we came to the lake, I proceeded along the strand, and Tontileaugo near the shore, sometimes paddling, and sometimes poleing his canoe along.

After some time the wind arose, and he went into the mouth of a small creek and encamped. Here we staid several days on account of high wind, which raised the lake in great billows. While we were here, Tontileaugo went out to hunt, and when he was gone a Wyandot came to our camp; I gave him a shoulder of venison which I had by the fire well roasted, and he received it gladly, told me he was hungry, and thanked me for my kindness. When Tontileaugo came home, I told him that a Wyandot had been at camp, and that I gave him a shoulder of roasted venison; he said that was very well, and I suppose you gave him also sugar and bear’s oil to eat with his venison. I told him I did not; as the sugar and bear’s oil was down in the canoe I did not go for it. He replied, you have behaved just like a Dutchman. 1 Do you not know that when strangers come to our camp we ought always to give them the best that we have? I acknowledged that I was wrong. He said that he could excuse this as I was but young; but I must learn to behave like a warrior, and do great things, and never be found in any such little actions.

The lake being again calm, 2 we proceeded, and arrived safe at Sunyendeand, which was a Wyandot town that lay upon a small creek which empties into the little lake below the mouth of Sandusky.

The town was about eighty rood above the mouth of the creek, on the south side of a large plain, on which timber grew, and nothing more but grass or nettles. In some places there were large flats where nothing but grass grew, about three feet high when grown, and in other places nothing but nettles, very rank, where the soil is extremely rich and loose, here they planted corn. In this town there were also French traders, who purchased our skins and fur, and we all got new clothes, paint, tobacco, &c.

After I had got my new clothes, and my head done off like a red-headed woodpecker, I, in company with a number of young Indians, went down to the cornfield to see the squaws at work. When we came there they asked me to take a hoe, which I did, and hoed for some time. The squaws applauded me as a good hand at the business; but when I returned to the town the old men, hearing of what I had done, chid me and said that I was adopted in the place of a great man, and must not hoe corn like a squaw. They never had occasion to reprove me for anything like this again; as I never was extremely fond of work, I readily complied with their orders.

As the Indians on their return from their winter hunt bring in with them large quantities of bear’s oil, sugar, dried venison, &c., at this time they have plenty, and do not spare eating or giving; thus they make way with their provision as quick as possible. They have no such thing as regular meals, breakfast, dinner, or supper; but if anyone, even the town folks, would go to the same house several times in one day, he would be invited to eat of the best; and with them it is bad manners to refuse to eat when it is offered. If they will not eat it is interpreted as a symptom of displeasure, or that the persons refusing to eat were angry with those who invited them.

At this time hominy, plentifully mixed with bear’s oil and sugar, or dried venison, bear’s oil, and sugar, is what they offer to everyone who comes in any time of the day; and so they go on until their sugar, bear’s oil, and venison are all gone, and then they have to eat hominy by itself, without bread, salt, or anything else; yet still they invite everyone that comes in to eat whilst they have anything to give. It is thought a shame not to invite people to eat while they have anything; but if they can in truth only say we have got nothing to eat, this is accepted as an honorable apology. All the hunters and warriors continued in town about six weeks after we came in; they spent this time in painting, going from house to house, eating, smoking, and playing at a game resembling dice, or hustle-cap. They put a number of plum-stones in a small bowl; one side of each stone is black, and the other white; they then shake or hustle the bowl, calling, hits, kits, hits, honesey, honesey, rago, rago; which signifies calling for white or black, or what they wish to turn up; they then turn the bowl, and count the whites and blacks. Some were beating their kind of drum and singing; others were employed in playing on a sort of flute made of hollow cane; and others playing on the jew’s-harp. Some part of this time was also taken up in attending the council house, where the chiefs, and as many others as chose, attended; and at night they were frequently employed in singing and dancing. Towards the last of this time, which was in June, 1756, they were all engaged in preparing to go to war against the frontiers of Virginia. When they were equipped, they went through their ceremonies, sung their war songs, &c. They all marched off, from fifteen to sixty years of age; and some boys, only twelve years old, were equipped with their bows and arrows, and went to war; so that none were left in town but squaws and children, except myself, one very old man, and another, about fifty years of age, who was lame.

The Indians were then in great hopes that they would drive all the Virginians over the lake, which is all the name they know for the sea. They had some cause for this hope, because, at this time, the Americans were altogether unacquainted with war of any kind, and consequently very unfit to stand their hand with such subtle enemies as the Indians were. The two old Indians asked me if I did not think that the Indians and French would subdue all America, except New England, which they said they had tried in old times. I told them I thought not. They said they had already drove them all out of the mountains, and had chiefly laid waste the great valley betwixt the North and South mountain, from Potomac to James River, which is a considerable part of the best land in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, and that the white people appeared to them like fools; they could neither guard against surprise, run, nor fight. These, they said, were their reasons for saying that they would subdue the whites. They asked me to offer my reasons for my opinion, and told me to speak my mind freely. I told them that the white people to the east were very numerous, like the trees, and though they appeared to them to be fools, as they were not acquainted with their way of war, yet they were not fools; therefore, after some time, they will learn your mode of war, and turn upon you, or at least defend themselves. I found that the old men themselves did not believe they could conquer America, yet they were willing to propagate the idea in order to encourage the young men to go to war.

When the warriors left this town, we had neither meat, sugar, or bear’s oil left. All that we had then to live on was corn pounded into coarse meal or small hominy; this they boiled in water, which appeared like well thickened soup, without salt or anything else. For some time we had plenty of this kind of hominy; at length we were brought to very short allowance, and as the warriors did not return as soon as they expected, we were in a starving condition, and but one gun in the town, and very little ammunition. The old lame Wyandot concluded that he would go hunting in a canoe, and take me with him, and try to kill deer in the water, as it was then watering time. We went up Sandusky a few miles, then turned up a creek and encamped. We had lights prepared, as we were to hunt in the night, and also a piece of bark and some bushes set up in the canoe, in order to conceal ourselves from the deer. A little boy that was with us held the light; I worked the canoe, and the old man, who had his gun loaded with large shot, when we came near the deer, fired, and in this manner killed three deer in part of one night. We went to our fire, ate heartily, and in the morning returned to town in order to relieve the hungry and distressed.

When we came to town the children were crying bitterly on account of pinching hunger. We delivered what we had taken, and though it was but little among so many, it was divided according to the strictest rules of justice. We immediately set out for another hunt, but before we returned a part of the warriors had come in, and brought with them on horseback a quantity of meat. These warriors had divided into different parties, arid all struck at different places in Augusta County. They brought in with them a considerable number of scalps, prisoners, horses, and other plunder. One of the parties brought in with them one Arthur Campbell, that is now Colonel Campbell, who lives on Holston River, near the Royal Oak. As the Wyandots at Sunyendeand and those at Detroit were connected, Mr. Campbell was taken to Detroit; but he remained some time with me in this town. His company was very agreeable, and I was sorry when he left me. During his stay at Sunyendeand he borrowed my Bible, and made some pertinent remarks on what he had read. One passage was where it is said, “It is good for man that he bear the yoke in his youth.” He said we ought to be resigned to the will of Providence, as we were now bearing the yoke in our youth. Mr. Campbell appeared to be then about sixteen or seventeen years of age.

There was a number of prisoners brought in by these parties, and when they were to run the gauntlet I went and told them how they were to act. One John Savage was brought in, a middle-aged man, or about forty years old. He was to run the gauntlet. I told him what he had to do; and after this I fell into one of the ranks with the Indians, shouting and yelling like them; and as they were not very severe on him, as he passed me, I hit him with a piece of pumpkin, which pleased the Indians much, but hurt my feelings.

About the time that these warriors came in, the green corn was beginning to be of use, so that we had either green corn or venison, and sometimes both, which was, comparatively high living. When we could have plenty of green corn, or roasting ears, the hunters became lazy, and spent their time, as already mentioned, in singing and dancing, &c. They appeared to be fulfilling the scriptures beyond those who profess to believe them, in that of taking no thought of tomorrow; and also in living in love, peace, and friendship together, without disputes. In this respect they shame those who profess Christianity.

In this manner we lived until October; then the geese, swans, ducks, cranes, &c., came from the north, and alighted on this little lake, without number, or innumerable. Sunyendeand is a remarkable place for fish in the spring, and fowl both in the fall and spring.

As our hunters were now tired with indolence, and fond of their own kind of exercise, they all turned out to fowling, and in this could scarce miss of success; so that we had now plenty of hominy and the best of fowls; and sometimes, as a rarity, we had a little bread, which was made of Indian corn meal, pounded in a hominy block, mixed with boiled beans, and baked in cakes under the ashes.

This with us was called good living, though not equal to our fat, roasted, and boiled venison, when we went to the woods in the fall; or bear’s meat and beaver in the winter; or sugar, bear’s oil, and dry venison in the spring.

Sometime in October, another adopted brother, older than Tontileaugo, came to pay us a visit at Sunyendeand, and he asked me to take a hunt with him on Cayahaga. As they always used me as a free man, and gave me the liberty of choosing, I told him that I was attached to Tontileaugo, had never seen him before, and therefore asked some time to consider of this. He told me that the party he was going with would not be along, or at the mouth of this little lake, in less than six days, and I could in this time be acquainted with him, and judge for myself. I consulted with Tontileaugo on this occasion, and he told me that our old brother Tecaughretanego (which was his name) was a chief, and a better man than he was, and if I went with him I might expect to be well used; but he said I might do as I pleased, and if I staid he would use me as he had done. I told him that he had acted in every respect as a brother to me; yet I was much pleased with my old brother’s conduct and conversation; and as he was going to a part of the country I had never been in, I wished to go with him. He said that he was perfectly willing.

I then went with Tecaughretanego to the mouth of the little lake, where he met with the company he intended going with, which was composed of Caughnewagas and Ottawas. Here I was introduced to a Caughnewaga sister, and others I had never before seen. My sister’s name was Mary, which they pronounced Maully. I asked Tecaughretanego how it came that she had an English name. He said that he did not know that it was an English name; but it was the name the priest gave her when she was baptized, which he said was the name of the mother of Jesus. He said there were a great many of the Caughnewagas and Wyandots that were a kind of half Roman Catholics; but as for himself, he said, that the priest and him could not agree, as they held notions that contradicted both sense and reason, and had the assurance to tell him that the book of God taught them these foolish absurdities: but he could not believe the great and good Spirit ever taught them any such nonsense; and therefore he concluded that the Indians’ old religion was better than this new way of worshipping God.

The Ottawas have a very useful kind of tents which they carry with them, made of flags, plaited and stitched together in a very artful manner, so as to turn rain or wind well each mat is made fifteen feet long, and about five feet broad. In order to erect this kind of tent, they cut a number of long straight poles, which they drive in the ground, in form of a circle, leaning inwards; then they spread the mats on these poles, beginning at the bottom and extending up, leaving only a hole in the top uncovered, and this hole answers the place of a chimney. They make a fire of dry split wood in the middle, and spread down bark mats and skins for bedding, on which they sleep in a crooked posture all round the fire, as the length of their beds will not admit of stretching themselves. In place of a door they lift up one end of a mat and creep in, and let the mat fall down behind them.

These tents are warm and dry, and tolerably clear of smoke. Their lumber they keep under birch-bark canoes, which they carry out and turn up for a shelter, where they keep everything from the rain. Nothing is in the tents but themselves and their bedding.

This company had four birch canoes and four tents. We were kindly received, and they gave us plenty of hominy, and wild fowl boiled and roasted. As the geese, ducks, swans, &c., here are well grain fed, they were remarkably fat, especially the green-necked ducks.

The wild fowl here feed upon a kind of wild rice that grows spontaneously in the shallow water, or wet places along the sides or in the corners of the lakes.

As the wind was high and we could not proceed on our voyage, we remained here several days, and killed abundance of wild fowl, and a number of raccoons.

When a company of Indians are moving together on the lake, as it is at this time of the year often dangerous sailing, the old men hold a council; and when they agree to embark, everyone is engaged immediately in making ready, without offering one word against the measure, though the lake may be boisterous and horrid. One morning, though the wind appeared to me to be as high as in days past, and the billows raging, yet the call was given yohoh-yohoh, which was quickly answered by all ooh-ooh, which signifies agreed. We were all instantly engaged in preparing to start, and had considerable difficulties in embarking.