The Choctaws, like all of their race, had no written laws, and their government rested alone on custom and usage, growing out of their possessions and their wants; yet was conducted so harmoniously by the influence of their native genius and experience, that one would hardly believe that human society could be maintained with so little artifice. As they had no money, their traffic consisted alone in mutual exchange of all commodities; as there was no employment of others for hire, there were no contracts, hence judges and lawyers, sheriffs and jails were unknown among them. There were no beg gars, no wandering tramps, no orphan children unprovided for in their country, and deformity was almost unknown, proving that nature in the wild forest of the wilderness is true to her type. Their chief had no crown, no sceptre, no bodyguards, no outward symbols of authority, nor power to give validity to their commands, but sustained their authority alone upon the good opinion of their tribe. No Choctaw ever worshiped his fellow man, or submitted his will to the humiliating subordinations of another, but with that sentiment of devotion that passed beyond the region of humanity, and brought him in direct contact with nature and the imaginary beings by whom it was controlled, which he divined but could not fathom; to these, and these alone, he paid his homage, invoking their protection in war and their aid in the chase.

The ancient Choctaws believed, and those of the present day believe, and I was informed by Governor Basil LeFlore, in 1884, (since deceased) that there is an appointed time for every one to die; hence suicide appeared to them, as an act of the meanest cowardice. Though they regarded it as a sacrilege to mention the names of their dead, still they spoke of their own approaching death with calmness and tranquility. No people on earth paid more respect to their dead, than the Choctaws did and still do; or preserved with more affectionate veneration the graves of their ancestors. They were to them as holy relics, the only pledges of their history; hence, accursed was he who should despoil the dead. They had but a vague idea of future rewards and punishments. To them a future life was a free gift of the Great Spirit, and the portals of the happy hunting grounds would be opened to them, in accordance, as their life had been meritorious as a brave warrior. They were utterly ignorant of the idea of a general resurrection, and it was difficult for them to be induced to believe that the body would again be raised up.

But today finds the Choctaws advanced in knowledge and improvement, which has produced a revolution in their moral and intellectual condition and in the current of their thoughts and ideas. Though seemingly slow to many has been their progress, yet not more so than other nations. For it must be remembered, that today there are many nations on the eastern continent, where a knowledge of letters has been known for centuries, and whose intellectual advantages have been much superior to that of the North American Indians, who have not yet reached that moral and intellectual culture that many tribes of the Indians have. It required over 2000, years for us to rise from a state of savage barbarity to our present state of advancement, though, tis true they have had, to a small extent, the advantages of pure civilization; but when we take into consideration the great disadvantages which even the five civilized tribes have labored under and the many oppositions they have had to encounter from first to last, in their commendable efforts to moral and intellectual improvement, (though enjoying the advantages of the teachings of the faithful and noble missionary for half a century) from the corrupting influences and pernicious examples of the base white men who have ever cursed their country, even as fated Egypt of old was cursed by the visitations of the locusts, frogs and lice, we have just and good reasons to be surprised that they have made the progress they have.

As a proof of the Indian’s love of country and the scenes of his childhood, so cruelly denied him by his oppressors, I will state that a few years after they had moved west, a few Choctaw warriors, seemingly unable to resist the desire of once more looking upon the remembered scenes of the unforgotten past, returned to the homes of their youth; for a few weeks they lingered around, the very personification of hopeless woe, with a peculiar something in their manner and appearance, which seemed to speak their thoughts as absently following a long dream that was leading them to the extreme limits of their once interminable fatherland. But their souls could not brook the change, or the ways of the pale-face. They gazed awhile, as strangers in a strange land, then turned in silence and sorrow from the loved vision they never would enjoy or look upon again, but which they never would forget, and once more directed their steps to ward the setting sun and were seen no more. But nothing strange in this; for who does not delight, even in after years, to return to the well-remembered walks of early life! The touch of the long vanished hands, and the echo of the voices, that are hushed, all seem to return, reminding us in touching accents of unutterable pathos, of the days that are no more! Again are we united with the days of childhood, calling up by gone joys. Truly, what a hallowing glory invests our past, beckoning us back to the haunts of boyhood s days! Again the songs we sang sweep over the harp of memory in tones of sweetest melody! Again the faces that early went down to the tomb, that cheerless habitation of the dead, smile on us with unchanging love and tenderness. The past! To every heart, what a fairyland. Who would not keep the memory of those days unsullied, unalloyed from those that raise sadness in the soul! Ah! As a token from some lost loved one, whose name is only spoken within the secrets of the heart, would I cherish and keep them with memories that never die.

The Indians have ever been termed a nomadic race, and as such have been represented by all who have written about them. There certainly never has a greater error been promulgated about any people. I refer to the southern Indians who formerly lived east of the Mississippi river. How far the Indians of the western plains may merit the title, I will not attempt to judge, being but little acquainted with their habits and customs, ancient or modern. But I have no fears in saying that no people merited less the appellation, nomadic, than those who formerly dwelt east of the Mississippi river. Webster, the standard authority, gives the definition of nomadic as signifying, “Moving from place to place,” and how that word could in any way justly be applied to the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Muskogee Indians, who were never known to move in the knowledge of the whites, until moved by them from their ancient domains to their present location, is a difficult matter to comprehend. In 150, De Soto found them in the very spot from which the government moved them in 1832, 1836, and 1840. In 1623, the early settlers of Virginia found them exactly where De Soto had left them. When the French established them selves in Mobile, Alabama, they found them still where the Virginia settlers had found them. In 1735, the Carolina traders found them exactly where De Soto, the Virginians and the French had found them. In 1744, Adair found them still where De Soto, the Virginians, the French, and the Carolina traders, had found them, and lived among the Chickasaws thirty years. In 1771, Roman still found them at the very place where De Soto, the Virginians, the French, the Carolina traders and Adair, had found them; and states, in his travels through the Choctaw Nation, he passed through seventy of their towns. In 1815, the missionaries still found them exactly where De Soto, the Virginians, the French, the Carolinian traders, Adair, and Roman had found them. In 1832, the United States Government found them still where De Soto, the Virginians, the French, the Carolina traders, Adair, Roman, and the missionaries had found them, and moved them to their present place of abode in 1832; and 1899, A. D. finds them just where the government put them sixty-seven years ago. So they have “moved from place to place once in 359 years, and then moved by the force of arbitrary power, they are called nomadic.

Of the Indians it may be truly said:

“But on the natives of that land misused,

Not long the silence of amazement hung,

Nor brooked they long their friendly faith abused;

For with a common shriek, the general tongue

Exclaimed, to arms! and fast to arms they sprung.”

They were truly men of the past, as well as men of the woods, yet noble and true, glorying in their ancestors, and living in their deeds by reverencing what they had handed clown to them.

The Choctaws, from their earliest history, have ever maintained their independence, and their love of country, amounting to almost idolatry, which cannot be described by words; and, in defending it, they utterly despised danger and mocked at fear.

Having no alphabet nor written language, their knowledge was conveyed to the eye by rude imitation. In the pictures of various animals which had been drawn on smooth substance, a piece of bark, or tree, there he recognized a symbol of his tribe; and in these various figures, which he saw sketched here and there, he read messages from his friends. The rudest painting, though silent and unintelligible to the white man, told its tale to the Choctaws. He abhorred restraint of any kind, while liberty, free and unrestrained, was the ruling passion of his soul; the natural and unrestrained propensities, of his wild nature were his system of morals, to which he firmly adhered and tenaciously followed. They had no calendar, but reckoned time thus: The months, by the full or crescents moons; the years by the killing of the vegetation by the wintry frosts. Thus, for two years ago the Choctaw would say: Hushuk (grass) illi (dead) tuklo (twice); literally, grass killed twice, or, more properly, two killings of the grass ago. The sun was called Nittak hushi the Day-sun; and the moon, Neuak hushi, the Night-sun and sometimes, Tekchi hushi the Wife of the sun. Their almanac was kept by the flight of the fowls of the air; whose coming and going announced to them the progress of the advancing and departing seasons. Thus the fowls of the air announced to the then blessed and happy Choctaw the progress of the seasons, while the beasts. “Of the field gave to him warning of the gathering and approaching storm, and the sun marked to him the hour of the day; and so the changes of time were noted, not by figures, but by days, sleeps, suns and moons-signs that spoke the beauty and poetry of nature. If a shorter time than a day was required to be indicated two parallel lines were drawn on the ground, a certain distance apart, then pointing to the sun he would say: “It is as long as it would take the sun to move from there to there.” The time indicated by the moon was from its full to the next; that of the year, from winter to winter again, or from summer to summer. To keep appointments, a bundle of sticks containing the exact number of sticks as there were days from the day of appointment to the appointed, was kept; and every morning one was taken out and thrown away, the last stick announced the arrival of the appointed. This bundle of twigs was called Fuli (sticks) kauah (broken) broken sticks.

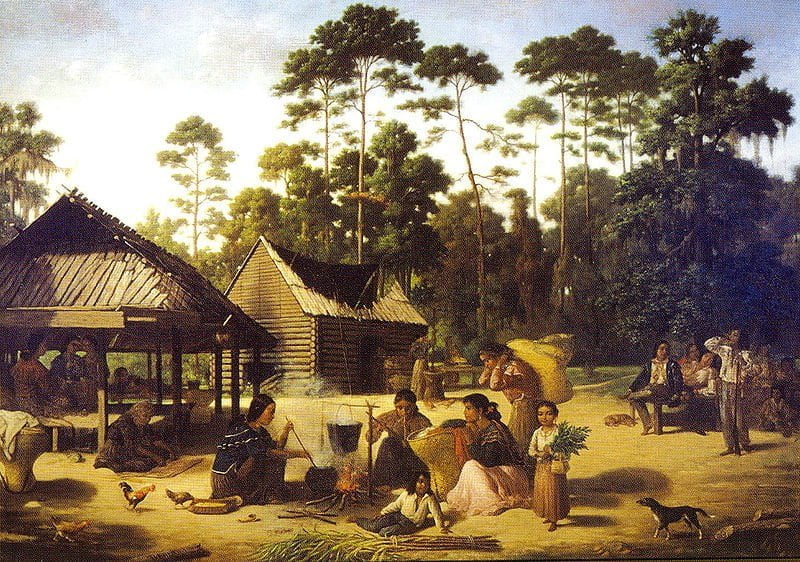

The abundant game of his magnificent and wide extended forests, which he never killed in wanton sport, no more than a white man would kill his cattle, but only as his necessities demanded, together with the fish of his beautiful streams, his fields of corn, potatoes, beans, with that of the inexhaustible supplies of spring and summer berries of fine variety and flavor, and winter nuts, all united to consummate his earthly bliss in rendering him a successful huntsman, a good fisherman, and cheerful tiller of the ground. The Choctaws have long been known to excel all the North American Indians in agriculture, subsisting to a considerable extent on the produce of their fields. In mental capacity the Choctaws, as a race of people, both ancient and modern, were and are not inferior to the whites; and their domestic life, as I know them seventy years ago, would sustain in many respects, a fair comparison with average civilized white communities. Their perspective faculties were truly wonderful; and the Choctaws of today, to whom the advantages of an education have been extended, have given indisputable evidence of as great capacity for a high order of education as any people on earth, I care not of what nationality.

There were no degrees of society among them, no difference in social gatherings; all felt themselves equal, of the same standing and on the same terms of social equality. And it is the same to day. They had no surnames, yet their names were peculiar, and most always significant, expressive of some particular action or incident; even as the names given to their hills, rivers, creeks, towns and villages. As those of ancient, classic fame in the eastern world, so to the superstitious mind of the Choctaw of the western world, caused him also to regard the sudden appearance of certain birds and their chirping s and twittering, the howl of the wolf and the lonely hoot of the owl, as omens of evil, while others, as omens of good; the spiritual significance of which, however, he interpreted according to the dictation of his own judgment, instead of that of an augur differing in this particular from his ancient brothers of Rome and Greece; yet like them he undertook no important enterprise without first consulting his trusted signs, whether auspicious or otherwise. If the former, he hesitated not its undertaking; if the latter, no inducement could be offered that would prevail upon him to undertake it; but he returned to his cabin and there remained for favorable omens.

But how far may be found a more just cause for admiration of the religious superstitions of the ancient Romans and Grecians than that of the North American Indians, it is difficult to see, since the Indians, alike with them, acknowledged, everywhere in nature, the presence of invisible beings; and it was the firm belief that his interests were under the special care of the Great and Good Spirit that the Choctaw warrior went upon the war-path, and the hunter sought the solitudes of his native forests in search of his game; and that his career in life was marked out for him by a decree that could not be altered. True, he was free to act, but the consequences of those actions were fixed beforehand; his daily food, life, joys, all, everything, were acknowledged as coming from the Great Spirit, who knew all things and imparted his wisdom to man; rewarded good deeds and punished crimes; implanted unwritten laws of right and wrong on the human heart, and unfolded to him coming events through dreams. The mystery of nature had its influence upon the untutored minds of all Indians, as well as its phenomena upon his senses; which, to them, were represented by the inferior spirits that surround the Great Spirit, who was the all-controlling deity; and to Him they all turned in gratitude for blessings, and for aid in all the affairs of life. Surely, it is the part of humanity in us, who have lived under a higher dispensation, in tracing the deep influences that the mythology of this strange, wonderful and peculiar people had over them; to admire rather than condemn without admitting the many extenuating circumstances. And though the rites and ceremonies of the Indians, by which they expressed their belief in their dependence on the Great Spirit, was made in offerings of corn, bread, fruits, etc, in stead of the sacrifices of animals; and sought omens in the actions of living animals, instead of an augury in the entrails of dead animals; yet the sincere feelings of piety, of gratitude and dependence, which gave origin to those offerings, gave origin also to that universal habit of self-examination and secret prayer to the Great Spirit, so characteristic of the Indian race. They believed that the Great Spirit communicated his will to man in dreams, in thunder and lightning, eclipses, meteors, comets, in all the prodigies of nature, and the thousands of unexpected incidents that occur to man. Could it be otherwise expected from those who walked by the light of nature alone? And though few assumed to have attained the power of revealing the import of these signs and wonders, yet many sought the coveted prize but found it not, therefore, became self-constituted prophets, but remained silent as to the character and functions of the spirits with whom they held their mysterious intercourse, thus leaving little foundation by which to identify their mythology. But that they derived their religious beliefs from the common seed with which man first started, there can be no doubt; but ere it had developed to any extent they strayed from the parent stock, and it assumed different aspects under differ-en circumstances, during the long period of isolation that en sued. Still, we find existing everywhere among mankind the same sensitiveness to the phenomena of nature, and the same readiness and power of imagining invisible beings as the cause of these phenomena.

The tendency of the Indian mind was thoroughly practical, stern and unbending, it was not filled with images of poetry nor high strung conceptions of fancy. He struggled for what was immediate, the war path, the chase and council life; but when not engaged therein, the life of the national games, under the head of social amusements, filled up the measure of his days the ball play, horse-race, foot-race, jumping and wrestling to them as honorable as the gymnastic exercises of the eastern nations of antiquity; enduring heat and cold, suffering” the pang’s of hunger and thirst, fatigue and sleeplessness. The object of the Indian boy also, was to gain all the experience possible in all manly exercises, therefore at an early age he went in search of adventures. Their tribal council consisted of the best, wisest and most worthy of the tribe. A fact from which we might draw many useful lessons. In its meetings, the most important topics of their country were the subjects of their deliberations; nor was the question ever asked in regard to any new question presented before that body, “If there was any money in it?” the good of their common country was the only thing discussed or even thought of. It was a body, which, in point of true dignity, if not of wisdom, has seldom been equaled and never surpassed; and which was regarded the supreme power of the tribal commonwealth. They had but few laws, but the few were rigidly enforced.