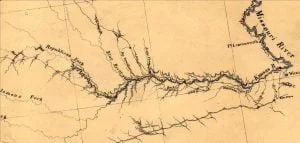

The Kansas town erected at the mouth of the Big Blue was established after Bourgmont’s visit to the tribes at the mouth of Independence Creek. The exact date can not now be fixed. It was probably about 1780. Lewis and Clark found their abandoned villages on the Missouri and their towns were then on the Kansas. One town was twenty leagues up this river, and the other twice that distance. The entry runs to this effect: This river (the Kansas) receives its name from a nation which dwells at this time on its banks, and has two villages one about twenty leagues, and the other forty leagues up. The location of the first village is not now certainly known, but it must have been near the present site of Topeka. There was a Kansas town immediately west of the present North Topeka at different periods after the expedition of Lewis and Clark. The upper village was at the mouth of the Big Blue. It was in Pottawatomie County between the Blue and the Kansas rivers, on a neck of land formed by the parallel courses of the two streams, and about two miles east of Manhattan. This became the sole residence of the Kansa before 1806, for in that year Captains Lewis and Clark, Doctor Sibley and Mr. Dunbar, made an exploration to discover the conditions of the Western Indians. The lower village had been abandoned and the inference is that the inhabitants had moved to the town at the mouth of the Blue. The entry on this subject is Eighty-leagues up the Kansas River, on the north side. And the report says they all lived in this one village. They furnished the traders with the skins of deer, beaver, black bear, otter (a few), and raccoon (a few). Also buffalo robes and buffalo tallow. This fur product brought the tribe about five thousand dollars annually in goods sent up from St. Louis. The general remarks on the Kansas made at that time by the explorers Lewis, Clark and others are of interest.

The limits of the country they claim is not known. The country in which they reside, and from thence to the Missouri, is a delightful one, and generally well watered and covered with excellent timber: they hunt on the upper part of Kanzas and Arkanzas rivers: Their trade may be expected to increase with proper management. At present they are a dissolute, lawless banditti; frequently plunder their traders, and commit depredations on persons ascending and descending the Missouri river: population rather increasing. These people, as well as the Great and Little Osages, are stationary, at their villages, from about the 15th of March to the 15th of May, and again from the 15th of August to the 15th of October: the balance of the year is appropriated to hunting. They cultivate corn, &c.

The town at the mouth of the Blue was partly depopulated about 1827. In that year an Agency for the Kansas Indians was established on Allotment No. 23, to Kansas half-breeds, on the north bank of the Kansas River, in what is now Jefferson County. At least, it was intended to build the Agency on that Allotment. It was in fact so near the east line of the tract that some of the buildings were on section 33, township 11, range 19, and on section 4, township 12, range 19, most of them on section 4, as was determined when the state was surveyed. This town was south of the station of Williamstown, on the Union Pacific Railway. There was a blacksmith and a farmer appointed for the Indians of the Agency, and these lived there. The farmer was Col. Daniel Morgan Boone, son of the great pioneer. Napoleon Boone, son of Col. D. M. Boone, was born there August 22, 1828, supposed to have been the first white child born in what was to become Kansas. The chief, Plume Blanche, White Plume, or Wampawara, was at the head of the village. Frederick Chouteau was the Indian trader. He had his trading-house on the south side of the river, on Horseshoe Lake, now Lakeview. It was at this Agency that Captain Bonneville crossed the Kansas River on his journey to the Rocky Mountains (1832). Marston G. Clark was U. S. Sub-Indian Agent there. The Captain spent the night with Chief White Plume, whom he found living in a substantial stone home, which had been erected for him by the Government. It is scarcely probable that all the Kansas Indians were gathered about this Agency. No doubt there were other villages up the Kansas River at that time. Some of the annuity payments provided for in the treaty when the great cession was concluded were made at this agency. The first was made at a trading-house near the mouth of the Kansas River, in what is now Wyandotte County. White Plume discovered in some way that his residence was over the line on the Delaware lands. While there would never have been any objection to this mistake or oversight of the white men who located the Agency buildings, White Plume was too proud to live on the land of another tribe. He abandoned his house and moved up the Kansas River. His house stood northwest of the Agency, and north of where the railroad station of Williamstown was located. Long before he moved his house had become uninhabitable, most of the woodwork having been torn out and used for fuel. It was alive with vermin. 1

When White Plume moved from the Agency the other Indians followed him. It was found unprofitable to maintain the Agency, and it was abandoned after 1832. The remainder of the population of the town at the mouth of the Blue had moved down the Kansas River by the year 1830. They had established three villages under the government of as many chiefs. Hard Chief had fixed his village, in 1830, about a mile above the mouth of what is now known as Mission Creek, on the south side of the river, from which his people carried their water. He had more than five hundred followers in his town. The American Chief’s village was on American Chief Creek (now called Mission Creek). It was some two miles from the Kansas River, and on the creek bottom. The town consisted of twenty lodges and about one hundred Indians. This village was also established in 1830. 2 They were built because Frederick Chouteau had told American Chief and Hard Chief that he would build a trading-house on the creek which he named American Chief Creek, for the chief who established his village on its banks. He did move there in 1830, and he and these two villages remained there until the removal of the tribe to the reservation at Council Grove. The other village established by the inhabitants of the town at the month of the Blue was that of Fool Chief. It was the largest, containing more than seven hundred people. It was on the north side of the river about a mile west of Papan’s Ferry. The location of this town must be determined by that of the ferry at that time, something difficult to do. The town is said to have been immediately north of the present town of Menoken. That would have put it inside the bounds of the lands belonging to the tribe. White Plume must have settled near the town of the Fool Chief when he moved up from the Agency. But there was another Kansas Village. Little is known of it, and its location is not clear. The only information concerning it is given by Fremont, in 1842, as follows:

The morning of the 18th, [of June] was very pleasant. A fine rain was falling, with cold wind from the north, and mists made the river hills look dark and gloomy, We left our camp at seven, journeying along the foot of the hills which border the Kansas valley, generally about three miles wide, and extremely rich. We halted for dinner, after a march of about thirteen miles, on the banks of one of the many little tributaries to the Kansas, which look like trenches in the prairies, and are usually well timbered. After crossing this stream, I rode off some miles to the left, attracted by the appearance of a cluster of huts near the mouth of the Vermillion. It was a large but deserted Kansas village, scattered in an open wood, along the margin of the stream, on a spot chosen with the customary Indian fondness for beauty of scenery. The Pawnees had attacked it in the early spring. Some of the houses were burnt, and others blackened with smoke, and weeds were already getting possession of the cleared places. Riding up the Vermillion river, I reached the ford in time to meet the carts, and, crossing, encamped on its western side.

On Fremont’s map this village is found to be on the Little Vermilion, a creek he delineates. But there is no such stream and there never was. In what is now Pottawatomie County, Kansas there is a Vermilion Creek. The Oregon Trail crossed it on what the official survey made section 24, township 9, range 10, two and one-half miles east of the present town of Louisville. There is where Fremont camped. From that point the Oregon Trail bore away from the Kansas River starting over the uplands for the Blue River. The Indian town was on the Vermilion below the crossing. Long’s detachment to visit the village at the mouth of the Blue crossed the Vermilion. This crossing was on the Indian trail which led up the Kansas River. This village was probably where the Indian trail crossed the Vermilion. Its inhabitants no doubt fled to the lower towns when driven out by the Pawnees.

There is a question as to when the missionaries turned attention to the Kansas Indians. At the Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church held at St. Louis, Mo., in 1830, Rev. Thomas Johnson was appointed a missionary to the Shawnees, and his brother, Rev. William Johnson, was appointed missionary to the Kansas Indians, Rev. William Johnson seems to have gone at once to the tribe to which he was appointed. According to one statement of Frederick Chouteau the Kansas Agency in what is now Jefferson County was maintained until 1830; and by another statement he fixed the date at 1832. If the Agency was kept up until 1832, Mr. Johnson spent the first two years of his missionary life there. If Mr. Chouteau moved his trading-house to Mission Creek, in Shawnee County, in 1830, then it was there that Mr. Johnson began his missionary labors. The probability is that it was at the more western location that he established the first Kansas Indian Mission, in 1830. In 1832 he was sent as missionary to the Delaware, where he remained about two years. He received then his second appointment to the Kansas Indian Mission, in 1834. He arrived on Mission Creek at the Kansas towns early in the summer, and began work on the mission buildings. These were erected on the northwest corner of section 33, township 11, range 14 east. The principal building was a hewed-log house thirty-six feet long and eighteen feet wide. It was a two-story structure, having four roomstwo below and two above. There was a huge stone chimney at each end. The kitchen was of logs, and apart from the house. There was a smoke-house and other building.

William Johnson labored at this mission until April, 1842, when he died. He accomplished little, and his hard work bore little fruit in the savage minds and hearts of the Kansas Indians. They could not be prevailed on to labor for their own support. They would not plant and cultivate corn and other grains, nor raise cattle. They went into the settlements by the hundred to beg. Rev. Thomas Johnson, brother to the missionary William, on his way to the Kansas Mission in May, 1837, met four hundred to five hundred of these Indians on their way to the Missouri settlements to beg.

In 1844 the widow of William Johnson was married to Rev. J. T. Peery, who was in that year sent to continue the work of Christianizing the Kansas Indians. Nothing of account was accomplished, and the school was discontinued. In 1846 the Kansas Indians were given a reservation at Council Grove. They soon removed to their new home. In 1850 the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, put up, at Council Grove, what was the best mission building ever erected in Kansas. It was built by Rev. T. S. Huffaker, who was long connected with the Kansas tribe. It still stands, the finest specimen of the buildings of its time, quaint, massive, silent, a splendid monument to the fine spirit of the Church which labored long, zealously, but in vain to make Christians of intractable savages.

In 1851, Mr. Huffaker opened his school. As few or no Indian children would attend, he admitted the children of white settlers, employees of the commerce which rolled over the Santa Fe Trail. It was one of the first schools in Kansas to receive white children. In after years Mr. Huffaker was constrained to admit that all attempts to educate the Kansas Indian children had failed. And these Indians never gave any serious attention the Christian religion.

Citations:

- The following notes, from Vol. IX, pp. 194-196, Kansas Historical Collections, are of interest here.

“Regarding the situation of the first Kaw agency, Daniel Boone, a son of Daniel Morgan Boone, government farmer of the Kaws, says in a letter to Mr. W. W. Cone, dated Westport, Mo., August 11, 1879: Fred Chouteau’s brother established his trading-post across the river from my father’s residence the same fall we moved to the agency, in the year 1827. The land reserved for the half-breeds belonged to the Kaws. The agency was nearly on the line inside of the Delaware land, and we lived half-mile east of this line, on the river.”

“Survey 23, the property of Joseph James, was the most easterly of the Kaw half-breed lands. The first Delaware land on the Kansas river east of this survey is section 4, township 12, range 19 east; hence the site of the old agency. August 16, 1879, Mr. Cone and Judge Adams, piloted by Thos. R. Bayne, owner of survey No. 23, visited the site of the agency. In the Topeka Weekly Capital of August 27, Mr. Cone says: We noticed on the east of the dividing line, over on the Delaware land, the remains of about a dozen chimneys, although Mr. Bayne says there were at least twenty when he came there, in 1854.”

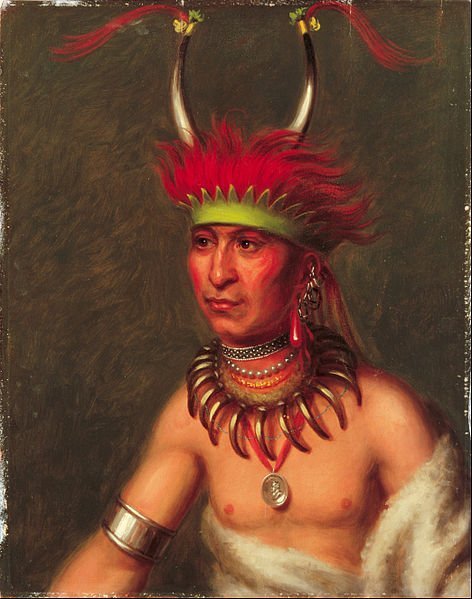

“John C. McCoy, in a letter to Mr. Cone, dated August, 1879, says: I first entered the territory August 15, 1830. . . . At the point described in your sketch, on the north bank of the Kansas river, seven or eight miles above Lawrence, was situated the Kansas agency. I recollect the following persons and families living there at that date, viz.: Marston G. Clark, United States sub-Indian agent, no family; Daniel M. Boone, Indian farmer, and family; Clement Lessert, interpreter, family, half-breeds; Gabriel Phillibert, government blacksmith, and family (whites); Joe Jim, Gonvil, and perhaps other half-breed families. . . . In your sketch published in the Capital you speak of the stone house or chimney, about two miles northwest of the Kansas agency. That was a stone building built by the government for White Plume, head chief of the Kanzans, in 1827 or 1828. There was also a large field fenced and broken in the prairie adjoining toward the east or southeast. We passed up by it in 1830, and found the gallant old chieftain sitting in state, rigged out in a profusion of feathers, paint, wampum, brass armlets, etc., at the door of a lodge he had erected a hundred yards or so to the northwest of his stone mansion, and in honor of our expected arrival the stars and stripes were gracefully floating in the breeze on a tall pole over him. He was large, fine-looking, and inclined to corpulency, and received my father with the grace and dignity of a real live potentate, and graciously signified his willingness to accept of any amount of bacon and other presents we might be disposed to tender him. In answer to an inquiry as to the reasons that induced him to abandon his princely mansion, his laconic explanation was simply too much fleas. A hasty examination I made of the house justified the wisdom of his removal. It was not only alive with fleas, but the floors, doors and windows had disappeared and even the casings had been pretty well used up for kindling-wood. “

“Mr. Cone gives the following description of White Plume’s stone house in his Capital article of August 27, 1879: Mr. Bayne showed us a pile of stone as all that was left of that well-known landmark for old settlers, the stone chimney. It was located fifty yards north of the present depot at Williamstown, or Rural, as it is now called. Mr. Bayne, in a letter dated August 12, says: The old stone chimney, or stone house to which you refer, stood on the southwest quarter of section 29, range 19, when I came here, in 1854. It was standing intact, except the roof and floors, which had been burnt. It was about 18×34, and two stories high. There was a well near it walled up with cut stone, and a very excellent job.'”

John T. Irving’s account of his visit to this village throws light on the character of the Indians, especially White Plume.

“We emerged from the wood, and I found myself again near the bank of the Kansas river. Before me was a large house, with a court-yard in front. I sprang with joy through the unhung gate, and ran to the door. It was open; I shouted: my voice echoed through the rooms; but there was no answer. I walked in; the doors of the inner chambers were swinging from their hinges and long grass was growing through the crevices of the floor. While I stood gazing around an owl flitted by, and dashed out of an unglazed window; again I shouted; but there was no answer; the place was desolate and deserted. I afterwards learned that this house had been built for the residence of the chief of the Kanza tribe, but that the ground upon which it was situated having been discovered to be within a tract granted to some other tribe, the chief had deserted it, and it had been allowed to fall to ruin. My guide waited patiently until I finished my examination, and then again we pressed forward. . . . We kept on until near daylight, when we emerged from a thick forest and came suddenly upon a small hamlet. The barking of several dogs, which came flying out to meet us, convinced me that this time I was not mistaken. A light was shining through the crevices of a log cabin; I knocked at the door with a violence that might have awakened one of the seven sleepers. Who dareand vot de devil you vant? screamed a little cracked voice from within. It sounded like music to me. I stated my troubles. The door was opened; a head garnished with a red nightcap was thrust out, after a little parley, I was admitted into the bedroom of a man, his Indian squaw and a host of children. As however, it was the only room in the house, it was also the kitchen. I had gone so long without food that, notwithstanding what I had eaten, the gnawings of hunger were excessive, and I had no sooner mentioned my wants, than a fire was kindled, and in ten minutes a meal (don’t exactly know whether to call it breakfast, dinner or supper) of hot cakes, venison, honey and coffee was placed before me and disappeared with the rapidity of lightning. The squaw, having seen me fairly started, returned to her couch. From the owner of the cabin I learned that I was now at the Kanza agency, and that he was the blacksmith of the place. About sunrise I was awakened from a sound sleep, upon a bearskin, by a violent knocking at the door. It was my Indian guide. He threw out broad hints respecting the service he had rendered me and the presents he deserved. That I could not deny: but I had nothing to give. I soon found out, however, that his wants were moderate, and that a small present of powder would satisfy him; so I filled his horn, and he left the cabin apparently well pleased. In a short time I left the house, and met the Kanza agent, General Clark, a tall, thin, soldier-like man, arrayed in an Indian hunting-shirt and an old fox-skin cap. He received me cordially, and I remained with him all day, during which time he talked upon metaphysics, discussed politics, and fed me upon sweet potatoes.”[↩]

- This is stated from what Frederick Chouteau told Judge F. C. Adams. See Vol. I, Kansas Historical Collections, page 287.

In a letter of Mr. Chouteau to W. W. Cone, May 5, 1880, he fixes the date as 1832. See Kansas Historical Collections, Vol. IX, page 196, note 54. These statements are incorrect. Captain Bonneville found the Agency there in May, 1832.[↩]