Among these detained in Beaverhead Valley because wagons could not go through from Lemhi to Salmon River was a party of which John White and John McGavin were members. This company, about the 1st of August, 1862, discovered placers on Willard or Grasshopper Creek, where Bannack City was built in consequence, which yielded from five to fifteen dollars a day to the hand. White, who is usually accredited with the discovery, having done so much for his fame, has left us no other knowledge of him or his antecedents, 1 save that he was murdered in December 1863. 2

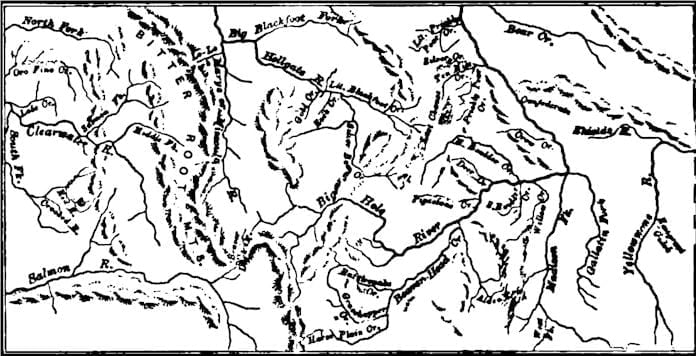

Almost at the same time Joseph K. Slack, born in Vermont in 1836, and who had been seeking his fortune in California and Idaho since 1858, discovered placers on the head of Bighole River that yielded fifty-seven dollars a day to the man. 3 Also about the same time John W. Powell discovered mines on North Bowlder Creek, in what was later Jefferson County. These repeated discoveries occasioned much excitement, and the Deer Lodge mines were abandoned for these east of the Rocky range.

In August a train arrived from Minnesota, under James Reed, like the others, in quest of Salmon River, but willingly tarrying in the Beaverhead Valley; 4 and several weeks later a larger train under James L. Fisk, which left Minnesota in July, by a route north of the Missouri, and was convoyed over the plains by a government escort. They were destined to Washington, but the greater part of the company resolved to put their fortunes to the test in the Rocky Mountains. 5

About four hundred persons wintered on Grasshopper Creek, and called the camp Bannack City after the aboriginals of that region, not knowing that in the Boise basin another Bannack City was being founded at the same time in the same way. 6 At Bighole mines were a few men who preferred wintering near their claims, 7 and a few others were scattered about the forks of the Missouri on land claims. 8 At Fort Benton were thirty or forty persons of different nationalities, such as attach themselves to fur companies. 8

At the Blackfoot agency, established in 1858 on Sun River, by Alfred J. Vaughn, agent for that tribe, were a few persons. 8 On the west side of the Rocky Mountains, in Missoula County, Washington, were over two hundred persons, inclusive of the mining, trading, missionary, and other classes. Of these Deer Lodge Valley had about seventy. 8 Already a town was laid off on the east side of Deer Lodge River, near its junction with the Hellgate, called La Barge City, the seat and centre of the business and population of Indian-trader antecedents, where the Antoines, Louis, and Baptistes were as numerous as over the border in the provinces. At the mission of St Ignatius, at Fort Owen, and in the Hellgate and Bitterroot valleys, were the greater part of the two hundred inhabitants, 8 who were not miners, but stock raisers and farmers, or settled in some regular occupation. How these six or eight hundred people passed the winter, midway between the Missouri River at Omaha and the lower Columbia, after the knowledge we have acquired of the American pioneer, it is not difficult to imagine. Building went on briskly, with such material as was at hand. Few were idle, and they were men with whom the vigilants came in time to deal peremptorily. On the road to Salt Lake teamsters kept their heavy wagons going until the snow in the passes closed them out. 9

As soon as spring opened, parties began to be made up for prospecting, not for mines only, but for eligible situations for town sites, it being already settled in the minds of the first comers that a large population was to follow in their wake. Such a company, under James Stuart, left Bannack April 9th for the mouth of the Stinkingwater River, where it was expected another division would join them. 10 This party, however, did not arrive in time, and were left to follow when they should strike the trail, Stuart continuing on with the advance to the Yellowstone country, which it was the design of the expedition to explore. The men remaining were only six in number; namely, Louis Simmons, George Orr, Thomas Cover, Barney Hughes, Henry Edgar, William Fairweather. They followed the trail of Stuart s party for some distance, but before overtaking them, were met by Crows, who, after robbing them, placed them on their own miserable sore-backed ponies, and ordered them to return whence they came. This treatment, which called out nothing but curses from the disappointed prospectors, eventuated in their highest good fortune. On their disconsolate journey back to Bannack they made a detour of a day’s journey up Madison River above their crossing, and passing through a gap to the southwest, encamped on a small creek, and proceeded to cook such scanty food as the Indians had left them, while Fairweather occupied his time in panning out some dirt in a gulch where he observed a point of bedrock projecting from the hillside. To his surprise he found thirty cents in coarse gold in the first panful of dirt, and upon a few more trials, $1.75 to the pan. After this discovery the explorers needed no sauce to their dinner. The stream was called Alder Creek, from its fringe of alder trees, and the place of discovery Fairweather gulch. It was sixty-five miles nearly due east from Bannack.

Claims were immediately staked off, and Hughes returned alone to Bannack to procure supplies, and inform such friends as the party desired to have share the benefits of the discovery. But a prospector is sharply watched, and when Hughes returned to Alder Creek, which proved to be one of the heads of Stinkingwater, 11 he was followed by two hundred men. Unable to prevent them, Hughes encamped a few hours’ ride from the mines. Having informed his friends, he stole away in the night with them, and so gave them time to make their locations before the others left camp.

When the two hundred arrived, a mining district was formed, named after Fairweather, with Dr Steele president and James Fergus recorder. This was on the 6th of June 1863. Eight months afterward there were five hundred dwellings and stores on Alder Creek; and Virginia City when a year old had a population of four thousand. 12 Like many other mining towns, it had a dual existence, consisting of two towns joining each other, the second one being called Nevada. 13 Together they made one long street, with side streets branching off at right angles. The joint city was twenty miles from the junction of Stinkingwater with the Jefferson fork, in latitude a little north of 45° and longitude 111½° west. It was 400 miles from Salt Lake, 1,400 from Omaha, 1,000 from Portland, 600 from navigation on the Columbia, and 500 from practicable navigation on the Missouri, except once, or perhaps twice, a year in good seasons, when steamboats could come to Fort Benton, 200 miles north. What did that matter? Gold smooth’s away all difficulties, and out of Alder Creek gulches, in the immediate vicinity of Virginia City, were taken, 14 in the first three years, $30,000,000. Five other districts were organized on Alder Creek – Highland, Pine Grove, and Summit up the stream, and Nevada and Junction below. About a thousand claims were located, which yielded well enough to pay a good profit when wages were from $10 to $14 a day.

But Alder Creek was not the only rich mining locality. A spur of the mountains which runs down between the Stinkingwater and Madison Rivers contained highly productive mines. Wisconsin gulch, so named because a Wisconsin company first worked it.

Bivens’ gulch, named after its discoverer, celebrated for course gold and nuggets weighing over three hundred dollars, Harris and California gulches, all paid largely. In this same spur of the mountains were a number of quartz veins bearing gold and silver, the value of which could only be guessed at from the richness of the placers.

We will now look after the party of James Stuart, which narrowly missed discovering the Alder Creek mines by hurrying on to the Yellowstone country instead of stopping to prospect where they found indications. 15 Keeping a generally northeast course, they crossed Madison River, finding plenty of burnt quartz, and ‘raising the color’ when prospecting; crossed the Gallatin Valley where it was watered by two forks, and found it superior to Deer Lodge; crossed the divide between the Missouri and the Yellowstone, reaching that river on the 25th, keeping down the south bank two days beyond Big Bowlder Creek, when they fell in with a band of Crows, from which they narrowly escaped through the intrepid behavior of Stuart. It became an almost daily occurrence to meet thieving Crows. They pursued their way down the Yellowstone, reaching Pompey’s Pillar on the 3d of May. 16 On the 5th they arrived at Bighorn River, where they found “from ten to fifty very fine colors of gold in every pan” taken from loose gravel on a bar near the mouth. On the 6th five men were detailed to lay out a town on the east side of this river, which they accordingly did, surveying 320 acres for the town site, and lots of 160 acres each surrounding it for the suburban possessions of the company. The stakes may be there still, but the town has not been peopled to this day.

On the 11th, as the party were travelling up the Bighorn, they discovered three white persons riding and leading pack-animals, whom they endeavored to intercept; but the strangers, taking them for road agents, escaped. 17

On the night of the 12th of May, Stuart’s camp was attacked, and Watkins, Bostwick, and Geery left dead in the Crow country. The survivors, on the 28th, after a toilsome journey, arrived at the Sweetwater, sixteen miles below Rocky Ridge, where they found good prospects in the loose gravel. On the 22d of June the company arrived at Bannack City, having travelled sixteen hundred miles since leaving it in April, and without having done more than learn the inhospitable nature of a large part of the country explored.

In August a company of forty-two men, most of them new arrivals, left Virginia City to explore the headwaters of the south fork of Snake River. 18 They were out 51 days, and travelled 500 miles, discovering much new country, but finding no rich deposits of gold. 19

Another expedition of this year was that of a large company of immigrants which started from St Cloud, Minnesota, under the escort of James L. Fisk, who conducted the Minnesota train of the year previous. 20 On both occasions he pursued the northern route; in 1863 via Fort Ripley, the Crow Wing Indian agency, Otter Tail City, Dayton, Fort Abercrombie, Thayen Oju River, lakes Lydia, Jessie, and Whitewood, the head of Mouse River, and the Cóteau du Missouri, crossing the White Earth, Porcupine, Milk, and Maria Rivers, reaching Fort Benton on the 6th of September. In his report, Fisk mentions that the farm at the Blackfoot agency was in charge of a Mr Clark, Vail having gone to the Bannack goldfield. Wheat, oats, and all kinds of vegetables were raised at the agency, and the Catholics had established a mission, St Peter’s, within fifteen miles of the place. The only farm in Prickly Pear Valley belonged to Morgan, who was erecting a large log house and outbuildings, covering a considerable area, the whole surrounded by a stockade ten feet in height. The population of Bannack and Virginia City together, he tells us, was twelve thousand in the early summer. 21

He sold the horses, cattle, and wagons belonging to the government at Virginia and Bannack cities, and returned via Salt Lake, travelling to that place by the Bannack City express, which was a covered wagon, leaving Bannack once a week with passengers. 22 At the ferry on Snake River, which was guarded by soldiers from General Connor’s army, 23 he found 150 wagons from Denver bound to the mines on the east slope of the Rocky Mountains, and farther on 400 more wagons, all with the same destination.

Almost in the light of expeditions must be considered the long journeys by freight trains. Usually a company was formed of several teams; but considering the small number of men who must guard a large amount of property on these journeys to and from Salt Lake and the Missouri River, the service was one requiring at times more than ordinary nerve. Twenty-five or thirty cents per pound was sometimes added to the river freights for the land transportation.

The condition of early society east of the mountains was not very different from that which we have seen in Idaho. If vice is hardly forced by the law’s awful presence to conceal itself under a cloaking of decency, how free is it to flaunt its filthiness where there is no law; and how apt are men, who under other circumstances would have avoided the exhibition of it, to indulge a prurient libertinism here. In the mines even the most reverend may study social problems from the life. Here, too, crime assumes gigantic proportions, and organizes for a war upon industry and thrift.

For a much more complete history of the road agents and vigilance committees of Montana than I have space for, I refer the reader to my Popular Tribunals, this series. The name of this extensive class, ‘road agents,’ which sprang up so quickly and disappeared so suddenly, became a mocking allusion to their agency in relieving travelers of whatever gold-dust or other valuables they might be carrying, and was preferred by these gentry to the more literal one of highway robbers. It is said, however, that the origin of the word came from the practice of the robbers of visiting overland stage stations, and, under the pretence of being agents of the mail line, changing their poor horses for better ones. The accoutrements of a road agent were a pair of revolvers, a double-barreled shotgun of large bore, with the barrels cut down short, and a knife. Mounted on a fleet and well-trained horse, disguised with mask and blankets, he lay in wait for his prey. When the victim approached near enough, out he sprang, on a run, with leveled gun, and the order, “Halt! throw up your hands!” Should the command be obeyed, the victim escaped with the loss of his valuables, the robber riding away, leaving the discomfited traveler to curse at his leisure. But if the traveler hesitated, or tried to escape, he was shot.

Chief among this class and head of a large criminal association was Henry Plummer, gentleman, baker, legislator, sheriff, and author of many murders and robberies. Villany was organized in strict accordance with law. When Plummer was sheriff of Bannack in 1863 his chief associates in crime were sworn in as deputies.

In October the coach of Peabody and Caldwell which ran between Virginia City and Bannack was halted in a ravine by two road agents and the passengers robbed of $2,800. In November Oliver’s Salt Lake coach left Virginia City and was robbed before reaching Bannack. One of the fraternity named Ives shot a man who threatened to give information. To rid themselves of Dillingham, first deputy sheriff at Virginia City – a good man who would not join the gang – three of them shot him. They, as well as Ives, were arrested. In the matter of the murderers of Dillingham, some were in favor of a trial by a jury of twelve men; others opposed it on the ground that Sheriff Plummer would pack the jury. It was at length agreed to put the matter to vote, and it was decided in mass meeting that the whole body of the people should act as jurors. Judge G. G. Bissell was appointed president of the court, with Steel and Rutar as associates. E. R. Cutler, a blacksmith, was appointed public prosecutor, and James Brown assistant, while H. P. A. Smith was attorney for the defense. Indictments were found against Stinson, one of the deputy sheriffs, and against Haze Lyons and Charles Forbes. In the cases of Stinson and Lyons a verdict of guilty was returned by the people. A vote being taken on the method of punishment, a chorus of “Hang them!” was returned, and men were set to erect a scaffold and dig graves. While these preparations were in progress Forbes was being tried. But the popular nerve had already begun to weaken, and besides, this murderer was a handsome fellow, tall, straight, agile, brave, and young, and the popular heart softened toward him. The same jury that condemned the others acquitted him on the false evidence of an accomplice and Forbes eloquent speech in his own behalf, by a nearly unanimous vote. His attorney even fell upon his neck and wept and kissed him. Hew could the crowd hang the other wretches after this turn of affairs? The prisoners themselves saw their advantage, and pleaded eloquently for their lives, and some women who were present joined their prayers to these of the doomed men. The farce concluded by another vote being taken on a commutation of sentence: they were simply banished, and hurriedly left the scene of popular justice. All this while poor Dillingham yet lay unburied, on a gambling-table in a brush wickiup. 24 Thus ended the first murder trial at Virginia City.

Ives, like Plummer and Forbes, was a gentlemanly rascal, 25 and many persons refused to believe him a common murderer. A large number of persons collected from the mines about to witness his trial. The counsel for the accused were: H. P. A. Smith, L. F. Richie, Wood J. Thurmond, and Alexander Davis. W. F. Sanders conducted the prosecution, assisted by Charles S. Bagg. Wilson was the judge. Sanders 26 mounted a wagon and made a motion that “George Ives be forthwith hanged by the neck until he is dead,” which resolution was at once adopted. He was hanged a few feet from the place of his trial.

Having dared to execute one murderer, the people breathed a little more freely. But it was plain that the whole community could not go on holding court to try all the desperadoes in the country, hundreds of whom deserved hanging. It was out of this necessity, to protect society without turning it into a standing army, which the first movement arose to form a vigilance committee. Soon after the execution of Ives, five citizens of Virginia City and one of Nevada City found each other taking steps in the direction of such a committee. In a few days the league extended to every part of what is now Montana, and two men were hanged on the 4th of January in Stinkingwater Valley.

Meanwhile evidence was accumulating against the chief of the road agents and his principal aids. Feeling sure of this, Plummer, Stinson, and Ray determined to lose no time in leaving the scene of their many crimes. But just as their preparations were about completed they were quietly arrested, taken to a gallows in waiting, and hanged. 27

During the month of January 1864 there were twenty-two executions in different parts of Montana. Smith and Thurmond, who defended Ives, were banished along with some spurious gold dust manufacturers.

Citations:

- I learned of McGavin from A. K. Stanton of Gallatin City, another of the immigrants of 1862, who mined first on Bighole River. Stanton was born in Pa, Dec. 1832. Was the son of a farmer, and learned the joiner’s trade. In 1856 he removed to Minnesota, and like many of the inhabitants of that state was much impressed with the fame of the Idaho mines. He started for Salmon River with a train of which James Reed was captain. He tried mining at Bannack, but not realizing his hopes, resolved to take some land in the Gallatin Valley and turn farmer and stock-raiser. He secured 440 acres of land, and presently has 80 horned cattle, 150 horses, and 17,000 sheep. In 1882 he married Jeanette Evenen.[↩]

- White and Rodolph Dorsett were murdered at the milk ranche on the road from Virginia City to Helena by Charles Kelly. Dimsale’s Montana Vigilantes, There seems to be no good reason for using the Spanish word vigilantes instead of its English equivalent ‘vigilants’ in these northern countries.[↩]

- Slack settled at or near Helena, and raised stock.[↩]

- In this train came John Potter, the Hoyts, Wooster Wyman, Charles Wyman, Still, Smith, Mark D. Leadbetter, French and son, and W. F. Bartlett. S. H. D., in Helena Rocky Mountain Gazette, Feb. 25, 1869.[↩]

- 1862 James L. Fisk, Minnesota Wagon Train and Residents of Bannack City, Montana 1862[↩]

- Montana Scraps, 9: Walla Walla Statesman, Dec. 6, 1862 Bonanza City Yankee Fork Herald, Jan. 3, 1880; Zabriskie’s Land Laws, 857-9[↩]

- Frederick H. Burr, James Coulan. Louis D. Ervin, and James M. Minesinger spent the winter in Bighole Valley.[↩]

- The list of white inhabitants of Montana in the winter of 1862, as given in the archives of the Historical Society of Montana, with additions from other authorities; and “though not a perfect roll, it contains over two thirds of all the population, according to the best accounts.

- The pais by Fort Lemhi, according to Granville Stuart, is the second lowest in toe Rocky range. The lowest is that which leads from Beaverhead Valley to Deer Lodge Valley, and the only one that never becomes impassable with snow, which seldom falls to a depth of more than 2 feet, while in the Dry Creek pass, as it is called, which was adopted for the Salt Lake route in 1863 it is sometimes 10 feet deep. Montana as It Is, 79-80. This little book of Stuart’s contains a great variety of information concerning the topography, climate, resources, nomenclature, routes, distances, etc., of Montana, and is an easy reference on all these subjects.[↩]

- James Stuart was chosen captain by these who presented themselves at the rendezvous. They were Cyrus D. Watkins, John Vanderbilt, James N. York, Richard McCafferty, James Hauxhurst, Drewyer Underwood, Samuel T. Hauser, Henry A. Bell, William Roach, A. Sterne Blake, George H. Smith, Henry T. Geery, Ephriam Bostwick, and George Ives. Con. Hist, Soc Montana, 150.[↩]

- So called by the Indians, from the sulphur springs which run into it.[↩]

- The town was first called Varina, after the wife of Jefferson Davis, but soon changed to Virginia. W. W. De Lacy, in Con. Hist. Soc. Montana, 113. G. G. Bissell, while acting as judge in the trial of Forbes, a road agent, re fused to write Varina at the head of a legal document, and wrote Virginia instead, which settled the matter. McClure’s Three Thousand Miles, 229.[↩]

- Central and Summit cities have since been added to the suburbs of Virginia.[↩]

- Aux Mining in Colorado and Montana, MS., 7-9; Ross Browne’s Rept; Frye’s Travelers’ Guide, 41; E. B. Neally, in Atlantic Monthly, Aug. 1866, 239. J. M. Carlton, born in Alderbaugh, Maine, in 1815, was a hotelkeeper at Virginia City. He located himself in Bannack in 1862, but removed to Virginia, of which he was mayor for several terms. He died April 22, 1876, leaving a wife and daughter. He had been one of the founders of St. Paul, Minnesota. Bozeman Avant-Courier, April 26, 1876[↩]

- Says Junes Stuart, in his journal of the Yellowstone expedition: ‘Today we crossed two small creeks and camped on the third one, near the divide between the Stinkingwater and Madison River…The country from the Stinkingwater to the divide in very broken, with deep ravines, with plenty of lodes of white quartz from 1 to 10 feet wide. In this camp Geery and McCafferty got a splendid prospect do a high bar, but we did not tell the rest of the party for fear of breaking up the expedition.’ This prospect was on a fork of Alder called Granite Creek. When the party returned they found these gulches full of miners. Con. Hist. Soc. Montana, l52-3.[↩]

- On this rock, named by Lewis and Clarke, Stuart found carved the names of Clarke and two of his men with the date, July 25, 1806. Also the names of Derick and Vancourt, dated May 23, 1834.[↩]

- They proved to be J. M. Bozeman, accompanied by the trader John M. Jacobs and his young daughter. They were looking for a wagon route from the three forks of the Missouri to Red Buttes on the North Platte, which they succeeded in finding, and which became known as the Bozeman cut-off. Bozeman laid out the town of that name in the Gallatin Valley, and was a man much respected for the qualities, which distinguish the actual pioneer. He met the fate, which has overtaken so many, being killed by Indians on the Yellowstone, near the mouth of Shield River, April 20, 1867.[↩]

- Their names were W. W. De Lacy, J. Bryant, S. Brown, A. R. Burr, David Burns, Lewis Casten, J. C. Davis, F. A. Dodge, John Ferril, J. H. Ferguson, George Forman, T. J. Farmerlee, Aaron Fiekel, S. R. Hillerman, Charles Heineman, H. H. Johnson, James Kelly, D. H. Montgomery, H. C. Mewhorter, A. H. Myers, J. B. Moore, John Morgan, W. H. Orcutt, J. J. Rich, Joseph W. Ray, H. Schall, W. Thompson, Major Brookie, E. P. Lewis, John Bigler, J. Stroup, Richard Tod, Jack Cummings, D. W. Brown, Charles Lamb, K. Whitcomb, A. Comstock, C. Failor, Charles Ream, J. Gallagher (hanged by vigilants). Smith, Dickie, J. H. Lawrence, R Sheldon. De Lacy, in Con. Hist. Soc, Montana, 140.[↩]

- De Lacy was employed by the first legislature of Montana to make a map of the country to assist in laying off counties and in this map was embodied the knowledge of his personal observations. It was lithographed and published, as also another in 1870. He also draughted a map of Montana in 1867 for the surveyor general’s office. In 1868 he wrote a letter on the railroad facilities of Montana, which was published in Raymond’s report of the Mines of the West the following year. In this letter he states his discoveries of Shoshone Lake, which he had called after himself, and the Madison Geysers. In 1872 Prof. Hayden visited these places, and failed to give proper credit; even after being reminded of it he neglected to do so, wishing, of course to appear as the discoverer of the lake, the true sore of Snake River, and the wonderful geyser basin at the head of the Madison.[↩]

- Fisk’s report is contained in H. Ex. Doc., 45, 28th cong. 1st and is extremely good in a descriptive and also in a historical sense.[↩]

- Immigrants of 1863

- 1863 Settlers in Lewis and Clarke County

- 1863 Settlers of Gallatin County

- 1863 settlers to Beaverhead County

- 1863 Settlers to Madison County

[↩]

- The expresses from the two Bannack cities, both in Idaho, in 1863, came together at the Snake River Ferry and made great confusion in distributing mail matter, the letters for Bannack or Idaho City often going to Bannack in Beaverhead Valley, and vice versa. Boise News, Sept. 29, 1863.[↩]

- Colonel P. Edward Connor of the 2d U. S. cavalry of Cal., known as the fighting second, in a battle on Bear River, Jan. 29, 1863, killed 278 Indians on the field and 25 in escaping across the river, not to mention 3 Indian women and 2 children butchered, and capturing all their property. This battle put an end to the killing of immigrants on that section of the road for several years. Connor was brevetted major general. He lost 20 killed, 49 wounded, and 69 who suffered amputation of fingers and toes from freezing. Virginia Montana Post, Feb. 9, 1867.[↩]

- A wickiup was a brush or willow tent, or shanty. They were made by laying cross-poles on four upright posts and covering them with bashes. Some made by the Indians were not over 6 feet square. In Montana the conical skin tent used by the mountain tribes was called a tepee.[↩]

- George Ives was from Ives Grove, Racine County, Wis., and a member of a highly respectable family. He caused an account of his death at the hands of Indians to be sent to his mother, to conceal from her his actual fate. Dimsdale’s, Vig. of Montana, 223.[↩]

- Sanders was a nephew of Judge Edgerton, first governor of Montana and sole authorized owner in the territory for some months. The vigilante give Edgerton their support, which also gave moral support to Sanders. The legislature subsequently confirmed some of the governor’s acts, and refused to confirm others. Undoubtedly his influence and that of his nephew was exerted for the public welfare.[↩]

- Dimsdale’s Vig, of Montana, 128. The author of this pamphlet was born under the flag of Great Britain, and was very English in sentiment, yet he fully justifies the first committee of safety in their executions. Dimsdale was a contributor to the Virginia and Helena Post, and became its editor. He was appointed by Gov. Edgerton superintendent of public instruction of Montana, was orator of the grand lodge of Masons, and possessed a large fund of general knowledge, with great versatility of talent. He prepared his book on the vigilants only two weeks before his death, which occurred Sept. 22, 1866, at the age of 35 years. He was pronounced ‘genial, generous, and good.’ Virginia and Helena Post, Sept. 29, 1866; Salt Lake Vidette, Oct 11, 1866.

Dimsdale says that the Magruder party were murdered by order of Plummer, and quotes the confession of Erastus Yager (who was nicknamed Red). Yager stated that of the band in Bannack and Virginia Plummer was chief, William Bunton second in command and stool pigeon, Samuel Bunton roadster (sent away by the band for being a drunkard), Cyrus Skinner roadster, fence, and spy. At Virginia City George Ives, Steven Marshland, John Wagner, Aleck Carter, William Graves, Buck Stinson, John Cooper, Mexican Frank, Bob Zachary, Boone Helm, George Lane, G. W. Brown, George Lowry, William Page, Doc. Howard, James Romaine (the last four were the murderers of the Magruder party), William Terwilliger, and G. Moore were roadsters. Frank Parrish and George Shears were roadsters and horse thieves. Ned Ray was council-room keeper. The password was “Innocent.” They wore their neckties in a sailor-knot, and shaved their beard down to moustache and chin whiskers. All the above were hanged; and afterward Jack Gallagher, Joseph Pizanthis, James Daniels, Jake Silvie (who had killed 12 men), John Keene, K. C. Rawley, John Dolan, James Kelly, James Brady, and William Hunter. For a multitude of other murders and hanging in Montana, see Popular Tribunals, this series.[↩]