Historian. The eighteenth century did some things with a splendor and a completeness, which is the despair of later, more restlessly striving generations. Barren though it was of poetry and high imagination, it gave birth to our most famous works in political economy, in biography, and in history; and it has set up for us classic models of imperishable fame. But the wisdom of Adam Smith, the shrewd observation of Boswell, the learning of Gibbon, did not readily find their way into the market place. Outside of the libraries and the booksellers’ rows in London and Edinburgh they were in slight demand. Even when the volumes of Gibbon, Hume, and Robertson had been added to the library shelves, where Clarendon and Burnet reigned before them, too often they only passed to a state of dignified retirement and slumber. No hand disturbed them save that of the conscientious housemaid who dusted them in due season. They were part of the furnishings indispensable to the elegance of a ‘gentleman’s seat’; and in many cases the guests, unless a Gibbon were among them, remained ignorant whether the labels on their backs told a truthful tale, or whether they disguised an ingenious box or backgammon board, or formed a mere covering to the wall.

The fault was with the public more than with the authors. Those who ventured on the quest would find noble eloquence in Clarendon, lively narrative in Burnet, critical analysis in Hume; but the indolence of the Universities and the ignorance of the general public unfitted them for the effort required to value a knowledge of history or to take steps to acquire it. It is true that the majestic style of Clarendon was puzzling to a generation accustomed to prose of the fashion inaugurated by Dryden and Addison; and that Hume and other historians, with all their precision and clearness, were wanting in fervor and imagination. But the record of English history was so glorious, so full of interest for the patriot and for the politician, that it should have spoken for itself, and the apathy of the educated classes was not creditable to them. Even so Ezekiel found the Israelites of his day, forgetful of their past history and its lessons, sunk in torpor and indifference. He looked upon the wreckage of his nation, settled in the Babylonian plain; in his fervent imagination he saw but a valley of dry bones, and called aloud to the four winds that breath should come into them and they should live.

In our islands the prophets who wielded the most potent spell came from beyond the Border. Walter Scott exercised the wider influence, Carlyle kindled the intenser flame. As artists they followed very different methods. Scott, like a painter, wielding a vigorous brush full charged with human sympathies, set before us a broad canvas in lively colors filled with a warm diffused light. Carlyle worked more in the manner of an etcher, the mordant acid eating deep into the plate. From the depth of his shadows would stand out single figures or groups, in striking contrast, riveting the attention and impressing themselves on the memory. Scott drew thousands of readers to sympathize with the men and women of an earlier day, and to feel the romance that attaches to lost causes in Church and State. Carlyle set scores of students striving to recreate the great men of the past and by their standards to reject the shibboleths of the present. However different were the methods of the enchanters, the dry bones had come to life. Mediaeval abbot and crusader, cavalier and covenanter, Elizabeth and Cromwell, spoke once more with a living voice to ears, which were opened to hear.

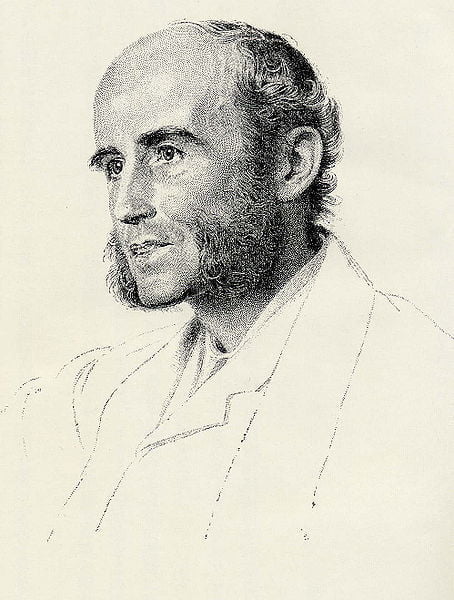

Nor did the English Universities fail to send forth men who could meet the demands of a generation, which was waking up to a healthier political life. The individual who achieved most in popularizing English history was Macaulay, who began to write his famous Essays in 1825, the year after he won his fellowship at Trinity, though the world had to wait another twenty-five years for his History of the English Revolution. Since then Cambridge historians like Acton, or Maitland, have equaled or excelled him in learning, though none has won such brilliant success. But it was the Oxford School, which did most, in the middle of the nineteenth century, to clear up the dark places of our national record and to present a complete picture of the life of the English people. Freeman delved long among the chronicles of Normans and Saxons; Stubbs no less laboriously excavated the charters of the Plantagenets; Froude hewed his path through the State papers of the Tudors; while Gardiner patiently unraveled the tangled skein of Stuart misgovernment. John Richard Green, one of the youngest of the school, took a wider subject, the continuous history of the English people. He was fortunate in writing at a time when the public was prepared to find the subject interesting, but he himself did wonders in promoting this interest, and since then his work has been a lamp to light teachers on the way.

In a twofold way Green may claim to be a child of Oxford. Not only was he a member of the University, but he was a native of the town, being born in the centre of that ancient city in the year of Queen Victoria’s accession. His family had been engaged in trade there for two generations without making more than a competence; and even before his father died in 1852 they were verging on poverty. Of his parents, who were kind and affectionate, but not gifted with special talents, there is little to be told; the boy was inclined, in after life, to attribute any literary taste that he may have inherited to his mother. From his earliest days reading was his passion, and he was rarely to be seen without a book. Old church architecture and the sound of church bells also kindled his childish enthusiasms, and he would hoard his pence to purchase the joy of being admitted into a locked-up church. So he was fortunate in being sent at the age of eight to Magdalen College School, where he had daily access to the old buildings of the College and the beautiful walks, which had been trodden by the feet of Addison a century and a half before. An amusing contrast could be drawn between the decorous scholar of the seventeenth century, handsome, grave of mien, calmly pacing the gravel walk, while he tasted the delights of classic literature, and little ‘Johnny Green’, a mere shrimp of a boy with bright eyes and restless ways, darting here and there, eagerly searching for anything new or exciting which he might find, whether in the bushes or in the pages of some romance which he was carrying.

But, for all his lively curiosity, Green seems to have got little out of his lessons at school. The classic languages formed the staple of his education, and he never had that power of verbal memory, which could enable him to retain the rules of the Greek grammar or to handle the Latin language with the accuracy of a scholar. He soon gave up trying to do so. Instead of aspiring to the mastery of accidence and syntax, he aimed rather at securing immunity from the rod. At Magdalen School it was still actively in use; but there were certain rules about the number of offences, which must be committed in a given time to call for its application. Green was clever enough to notice this, and to shape his course accordingly; and thus his lessons became, from a sporting point of view, an unqualified success.

But his real progress in learning was due to his use of the old library in his leisure hours. Here he made acquaintance with Marco Polo and other books of travel; here he read works on history of various kinds, and became prematurely learned in the heresies of the early Church. The views, which he developed, and perhaps stated too crudely, did not win approval. He was snubbed by examiners for his interest in heresiarchs, and gravely reproved by Canon Mozley for justifying the execution of Charles I. The latter subject had been set for a prize essay; and the Canon was fair-minded enough to give the award to the boy whose views he disliked, but whose merit he recognized. Partial and imperfect though this education was, the years spent under the shadow of Magdalen must have had a deep influence on Green; but he tells us little of his impressions, and was only half conscious of them at the time. The incident, which perhaps struck him most, was his receiving a prize from the hands of the aged Dr. Routh, President of the College, who had seen Dr. Johnson in his youth, and lived to be a centenarian and the pride of Oxford in early Victorian days.

Green’s school life ended in 1852, the year in which his father died. He was already at the top of the school; and to win a scholarship at the University was now doubly important for him. This he achieved at Jesus College, Oxford, in December 1854, after eighteen months spent with a private tutor; and, as he was too young to go into residence at once, he continued for another year to read by himself. Though he gave closer attention to his classics he did not drop his general reading; and it was a landmark in his career when at the age of sixteen he made acquaintance with Gibbon.

His life as an undergraduate was not very happy and was even less successful than his days at school, though the fault did not lie with him. Shy and sensitive as he was, he had a sociable disposition and was naturally fitted to make friends. But he had come from a solitary life at a tutor’s to a college where the men were clannish, most of them Welshmen, and few of them disposed to look outside their own circle for friends. Had Green been as fortunate as William Morris, his life at Oxford might have been different; but there was no Welshman at Jesus of the caliber of Burne-Jones; and Green lived in almost complete isolation till the arrival of Boyd Dawkins in 1857. The latter, who became in after years a well-known professor of anthropology, was Green’s first real friend, and the letters which he wrote to him show how necessary it was for Green to have one with whom he could share his interests and exchange views freely. Dawkins had the scientific, Green the literary, nature and gifts; but they had plenty of common ground and were always ready to explore the records of the past, whether they were to be found in barrows, in buildings, or in books. If Dawkins was the first friend, the first teacher who influenced him was Arthur Stanley, then Canon of Christ Church and Professor of Ecclesiastical History. An accident led Green into his lecture-room one day; but he was so much delighted with the spirit of Stanley’s teaching, and the life, which he imparted to history, that he became a constant member of the class. And when Stanley made overtures of friendship, Green welcomed them warmly.

A new influence had come into his life. Not only was his industry, which had been feeble and irregular, stimulated at last to real effort; but his attitude to religious questions and to the position of the English Church was at this time sensibly modified. He had come up to the University a High Churchman; like many others at the time of the Oxford Movement, he had been led half-way towards Roman Catholicism, stirred by the historical claims and the mystic spell of Rome. But from now onwards, under the guidance of Stanley and Maurice, he adopted the views of what is called the ‘Broad Church Party’, which suited his moral fervor and the liberal character of his social and political opinions.

Despite, however, the stimulus given to him (perhaps too late) by Dawkins and Stanley, Green won no distinctions at the University, and few men of his day could have guessed that he would ever win distinction elsewhere. He took a dislike to the system of history-teaching then in vogue, which consisted in demanding of all candidates for the schools a knowledge of selected fragments of certain authors, giving them no choice or scope in the handling of wider subjects. He refused to enter for a class in the one subject in which he could shine, and managed to scrape through his examination by combining a variety of uncongenial subjects. This was perverse, and he himself recognized it to be so afterwards. All the while there was latent in him the talent, and the ambition, which might have enabled him to surpass all his contemporaries. His one literary achievement of the time was unknown to the men of his college, but it is of singular interest in view of what he came to achieve later. He was asked by the editor of the Oxford Chronicle, an old-established local paper, to write two articles on the history of the city of Oxford. To most undergraduates the town seemed a mere parasite of the University; to Green it was an elder sister. Many years later he complained in one of his letters that the city had been stifled by the University, which in its turn had suffered similar treatment from the Church. To this task, accordingly, he brought a ready enthusiasm and a full mind; and his articles are alive with the essence of what, since the days of his childhood, he had observed, learnt, and imagined, in the town of his birth. We see the same spirit in a letter, which he wrote to Dawkins in 1860, telling him how he had given up a day to following the Mayor of Oxford when he observed the time-honored custom of beating the bounds of the city. He describes with gusto how he trudged along roads, clambered over hedges, and even waded through marshes in order to perform the rite with scrupulous thoroughness. But it was years before he could find an audience who would appreciate his power of handling such a subject, and his University career must, on his own evidence, be written down a failure.

When it was over he was confronted with the need for choosing a profession. It had strained the resources of his family to give him a good education, and now he must fend for himself. To a man of his nature and upbringing the choice was not wide. His age and his limited means put the Services out of the question; nor was he fitted to embark in trade. Medicine would revolt his sensibility, law would chill his imagination, and journalism did not yet exist as a profession for men of his stamp. In the teaching profession, for which he had such rare gifts, he would start handicapped by his low degree. In any case, he had for some time cherished the idea of taking Holy Orders. The ministry of the Church would give him a congenial field of work and, so he hoped, some leisure to continue his favorite studies. Perhaps he had not the same strong conviction of a ‘call’ as many men of his day in the High Church or Evangelical parties; but he was, at the time, strongly drawn by the example and teaching of Stanley and Maurice, and he soon showed that it was not merely for negative reasons or from half-hearted zeal that he had made the choice. When urged by Stanley to seek a curacy in West London, he deliberately chose the East End of the town because the need there was greater and the training in self-sacrifice was sterner; and there is no doubt that the popular sympathies, which the reading of history had already implanted in him, were nourished and strengthened by nine years of work among the poor. The exertion of parish work taxed his physical resources, and he was often incapacitated for short periods by the lavish way in which he spent himself. Indeed, but for this constant drain upon his strength, he might have lived a longer life and left more work behind him.

Of the parishes, which he served, the last and the most interesting was St. Philip’s, Stepney, to which he went from Hoxton in 1864. It was a parish of 16,000 souls, lying between Whitechapel and Poplar, not far from the London Docks. Dreary though the district seems to us to-day-and at times Green was fully conscious of this-he could re-people it in imagination with the men of the past, and find pleasure in the noble views on the river and the crowded shipping that passed so near its streets. But above all he found a source of interest in the living individuals whom he met in his daily round and who needed his help; and though he achieved signal success in the pulpit by his power of extempore preaching, he himself cared more for the effect of his visiting and other social work. Sermons might make an impression for the moment; personal sympathy, shown in the moment when it was needed, might change the whole current of a life.

For children his affection was unfailing; and for the humors of older people he had a wide tolerance and charity. His letters abound with references to this side of his work. He tells us of his ‘polished’ pork butcher and his learned parish clerk, and boasts how he won the regard of the clerk’s Welsh wife by correctly pronouncing the magic name of Machynlleth. He gave a great deal of time to his parishioners, to consulting his churchwardens, to starting choirs, to managing classes and parish expeditions. He could find time to attend a morning police court when one of his boys got into difficulties, or to hold a midnight service for the outcasts of the pavement.

When cholera broke out in Stepney in 1866, Green visited the sick and dying in rooms that others did not dare to enter, and was not afraid to help actively in burying those who had died of the disease. At holiday gatherings he was the life and soul of the body, ‘shocking two prim maiden teachers by starting kiss-in-the-ring’, and surprising his most vigorous helpers by his energy and decision. On such occasions he exhausted himself in the task of leadership, and he was no less generous in giving financial help to every parish institution that was in need.

What hours he could snatch from these tasks he would spend in the Reading Room of the British Museum; but these were all too few. His position, within a few miles of the treasure houses of London, and of friends who might have shared his studies, must have been tantalizing to a degree. To parish claims also was sacrificed many a chance of a precious holiday. We have one letter in which he regretfully abandons the project of a tour with Freeman in his beloved Anjou because he finds that the only dates open to his companion clash with the festival of the patron saint of his church. In another he resists the appeal of Dawkins to visit him in Somerset on similar grounds. His friend may become abusive, but Green assures him emphatically that it cannot be helped. ‘I am not a pig,’ he writes; ‘I am a missionary curate…. I could not come to you, because I was hastily summoned to the cure of 5,000 costermongers and dock laborers.’ We are far from the easy standard of work too often accepted by ‘incumbents’ in the opening years of the nineteenth century.

Early in his clerical career he had begun to form plans for writing on historical subjects, most of which had to be abandoned for one reason or another. At one time he was planning with Dawkins a history of Somerset, which would have been a forerunner of the County Histories of the twentieth century. Dawkins was to do the geology and anthropology; Green would contribute the archaeology and history. In many ways they were well equipped for the task